January Books

I’m not sure why but as the year turned, I found myself on a bit of a non-fiction kick. Whether because tiredness at the end of the academic year made me unable to lose myself in a fictional world, or a hankering after facts, cold hard facts written in black and white to counteract the prevailing winds in this “post factual” world, who can say. Whatever, it was a welcome feeling, this desire to read non-fiction, as I’d spent the year stockpiling books for just such an occasion.

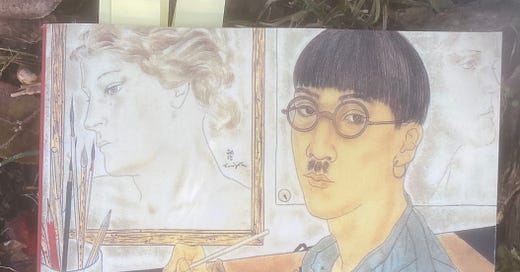

Phyllis Birnbaum’s biography of Tsuguhara Foujita (the name is spelled the way the French did, not the typical Japanese way: Fujita) is part of my research for a novel I am planning/intermittently working on/dreaming about, concerning a Japanese painter in Paris in the 1920s. Foujita was just such a painter, though not my painter, and so I assumed I could get a lot of background, colour, and artistic insight from this book, and pleasingly, I was right. I had heard of Foujita before but didn’t really know much about him. He was the most successful of the Japanese painters who went to Europe, something of a sensation in Paris where his work combined with his flamboyant fashion and main character energy helped him carve a niche where many others failed. Then the war came and he returned to Japan, enthusiastically turning his skills to war propaganda, something from which his reputation never recovered (I wondered a few times how much Foujita influenced Kazuo Ishiguro when writing An Artist of the Floating World, my favourite Ishiguro). Birnbaum is an excellent writer, a solid historian but one who isn’t afraid to insert herself into the story, recounting anecdotes about her research process, meeting people who knew Foujita, and the many arguments she had with Foujita scholars, some of whom will never forgive the artist, others who seek to excuse him completely. This is, in other words, completely my kind of book.

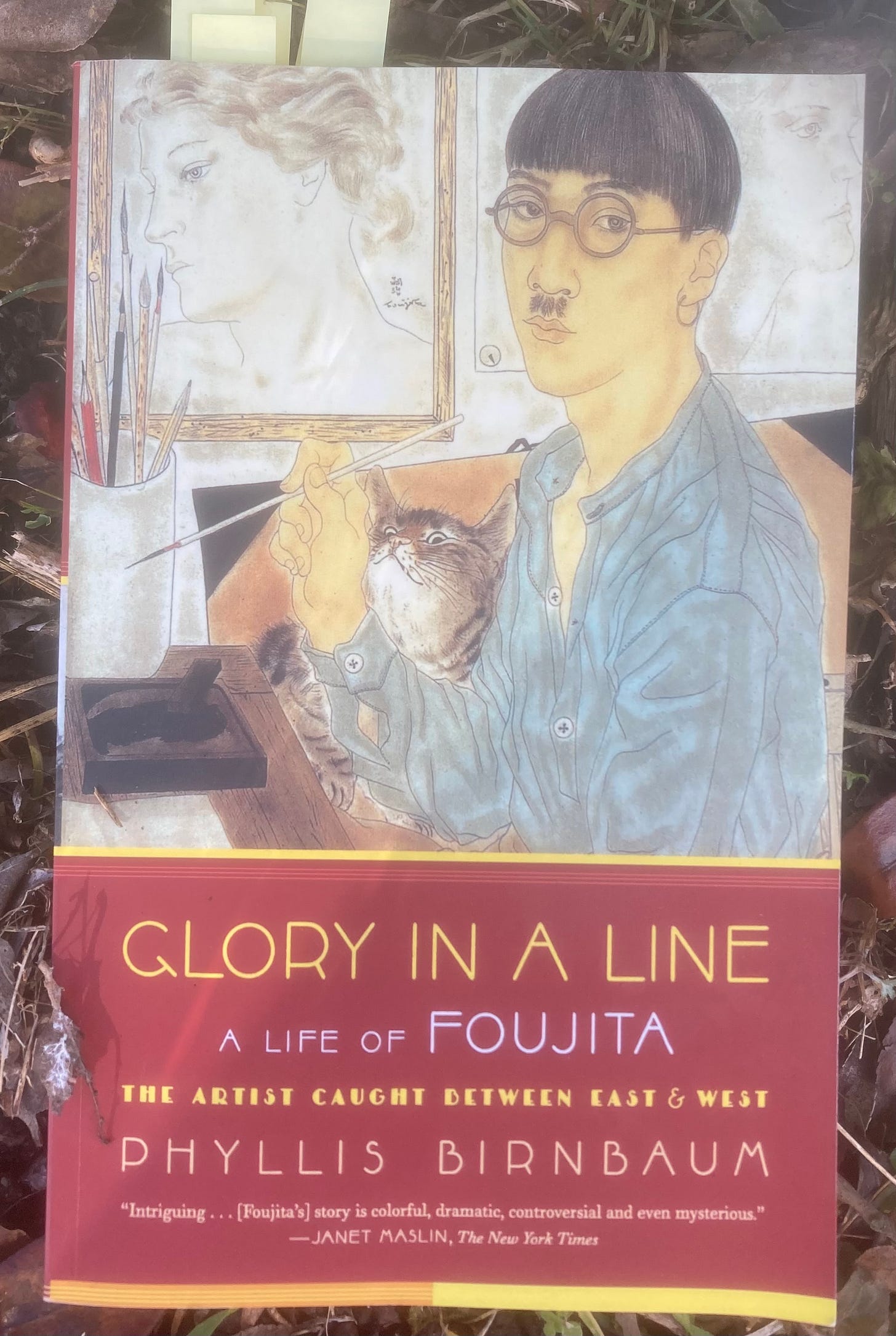

I picked this up, unsurprisingly, in Istanbul last summer, at the Museum of Innocence (I wrote all about this here). It is billed as something of a biography of the city and I envisaged Peter Ackroyd’s biography of London, but in actuality it is a memoir of Pamuk’s childhood through the filter of the city he has lived in his whole life. I’m personally not much of a fan of childhood memoirs, since the reasons I am interested in the person usually begin much later (I hate autobiographies that end volume one on the brink of success, for example) but Pamuk is such a compelling writer and his love for the city is so palpable that I could forgive the long passages about family dynamics that, frankly, I couldn’t care less about. As always with post-Nobel Pamuk, there’s a lot of self-indulgence but the blend of history, autobiography, humour, and pathos makes this a worthwhile read. I wonder how it would have landed had I not visited Istanbul this year and therefore had fresh memories and impressions of the city (I was delighted, for example, to discover that a meandering stroll Minori and I took on our last day was coincidentally almost identical to one he took regularly as a younger man). I think this is maybe a book I’ll return to again to pick out sections: he writes about other Turkish writers, for example, who I have never read so those sections made little sense to me. I’d like to read those writers, then reread what Pamuk has to say about them. It’s not Pamuk’s best but a good addition to the shelf.

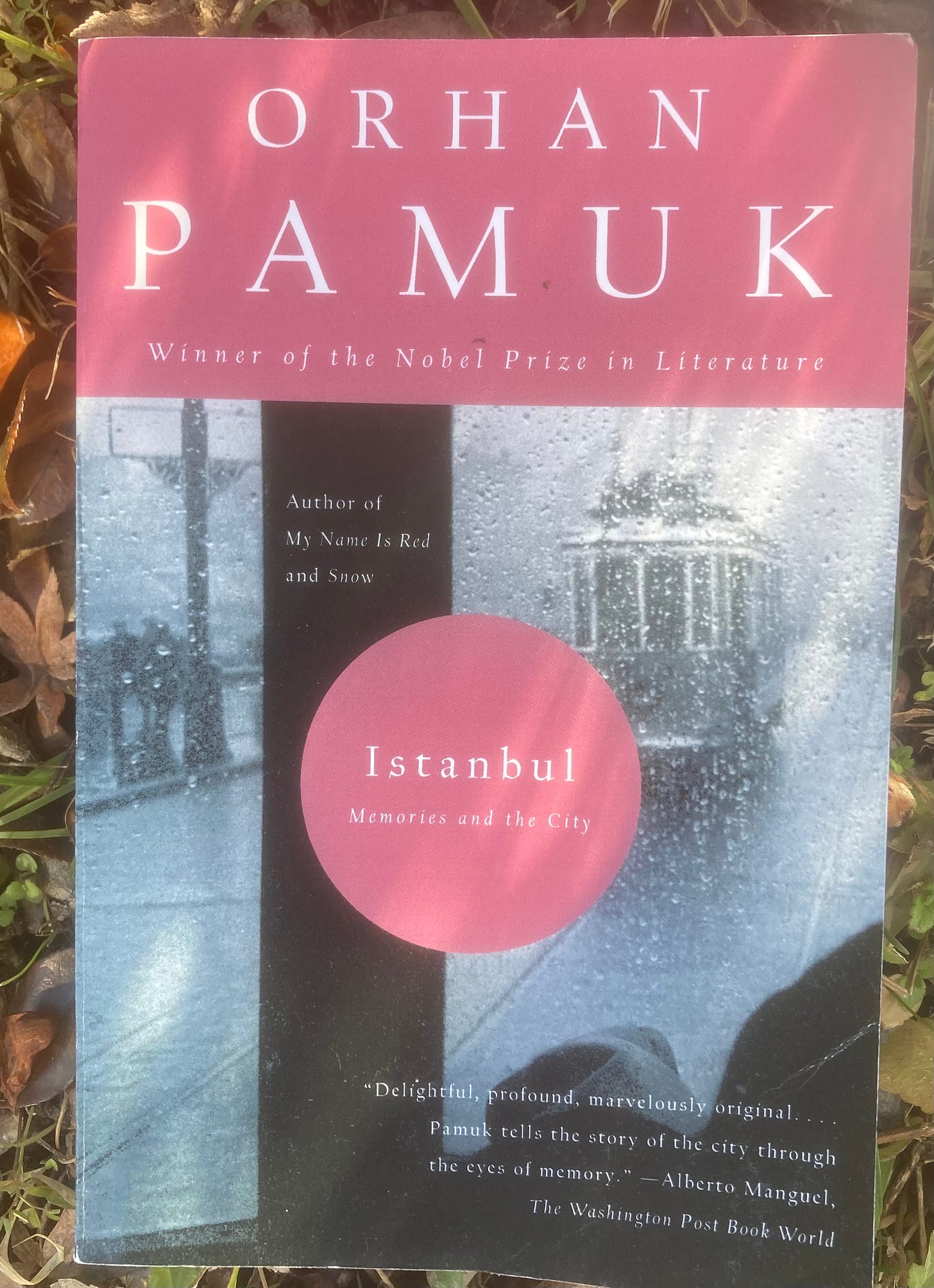

It’s been a long time since Rodge Glass had a book out and he’s back with a bang. This memoir is heartbreaking in its honesty. It concerns the condition HHT (Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia) which runs in Rodge’s family. Rodge showed symptoms for years but never got himself tested. His nephew Joshua was born with it which caused complications in his lungs, and Joshua only lived for three hours. Rodge writes beautifully and brutally about his guilt: perhaps, he wonders, if he had got checked out earlier, then his brother could have made a more informed choice about the risks involved in having a child. It’s also a love letter to literature, and the way people like Rodge (and me) use the words of others to filter and understand our own experiences. A powerful book crammed with ideas.

Another childhood memoir—two in fact—from a writer I greatly admire. I’d put off reading these because they are so focused on childhood: there’s nothing in either volume about Galloway the writer, and that’s the Galloway I’m interested in. She writes movingly and wittily about the trauma of her childhood, her drunk then absent father, her abusive older sister, and her eventual escape from it all. As a window into Scotland in the sixties and seventies, it is a wonderful piece of social history, and I could wallow in Galloway’s prose forever, but for me it will always be her fiction—The Trick is to Keep Breathing, the amazing Clara—that I return to, not these memoirs.

It wasn’t all non-fiction. I completed Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy with Cities of the Plain. I honestly don’t know if I can put into words why I liked this. Lots and lots of nothing happens. Most of it is atmosphere, seemingly empty dialogue, and descriptions of the day to day work on a ranch. The climax would be the inciting incident in most novels. So what is it? His prose, for one; the way his sentences draw you so easily into the world of Texan ranches, Mexican brothels, and the vast, empty, but somehow claustrophobic American west. The characters, for another, men that I would steer clear of in real life, men who only let tiny shafts of themselves spill out from behind thick, dense masks, men permanently caught between fight and flight but who, here, are endlessly fascinating. The toxic masculinity of it all, the tragic ends men meet because no one ever taught them how to process their emotions beyond drinking, fighting, and fucking. McCarthy has become one of those problematic writers now the truth about his relationship with a 16 year old while he was 42 has come out, but perhaps that’s why he could write this stuff so well. McCarthy’s grand theme is the existential crisis of modern masculinity and in order to explore that, you need to be saturated in that crisis: we’re never going to have novels that attempt to understand problematic men if we don’t let problematic men write about what they know. The saddest thing in these books is that all the tragedy could be avoided if these men just said what was on their minds, revealed what was in their hearts. There are funny memes going round about men not speaking to each other, making it seem almost a virtue, or at least inevitable, that men will spend hours, days, months in each other’s company without ever talking about how they are feeling. “Boys will be boys.” McCarthy’s books—whether he meant it or not—are a study into why men being stoic, silent, contained, is a bad idea. It’s tragic, and it’s our own damn fault. I feel fortunate that I was raised—and I don’t mean that solely in a childhood sense but in terms of maturation—by women—family, friends, girlfriends—who didn’t accept “boys will be boys” and thought it was possible to educate men, to make us self-aware, to teach us—even though it wasn’t their responsibility—to be better, and I was fortunate to be surrounded at an impressionable age by other men who took these lessons to heart too and therefore served as role models. I’m not saying I’m perfect, or even good, but I was lucky enough to be shown an alternative to that kind of masculinity and thus I can recognise that the kind of consequences McCarthy writes about come from men not having an outlet, a healthy way to deal with the tremors of life. It’s not a weakness to feel. It’s not a weakness to want to talk, but we’re often taught it is. As a man, quite often no one has ever said to you, “hey, do you want to talk about it?” The answer may be, “no,” but it’s the asking of the question that’s important. Sure, a few beers, a round of golf, watching the football may work better in that specific instance, but knowing the option is there, that someone will listen to you without judgement... McCarthy’s books, for me, show what happens when men don’t have that option.