The Museum of Innocence

At the end of July, we went to Türkiye—Istanbul and Cappadocia to be specific—for a bit of a well-deserved break. For both of us it was our first visit but it definitely won’t be the last. We had a wonderful time and I would urge anyone to go: great food, friendly people, one of the most photogenic countries I’ve ever been to, and lashings of history on every street corner.

Why I bring it up here though is because Istanbul is also the stomping ground and inspiration for one of my favourite writers, Orhan Pamuk. I’ve loved Pamuk’s work since I read Snow and then My Name is Red, his two undisputed masterpieces. I’ve written elsewhere on Substack about how his output can be hit or miss, not least since he won the Nobel and fell into that category of “too big to edit”. Nights of Plague, his most recent book, was flabby, overlong, and, on occasion, boring. Another book that could be tarred with the same brush is The Museum of Innocence, his first novel published after the Nobel.

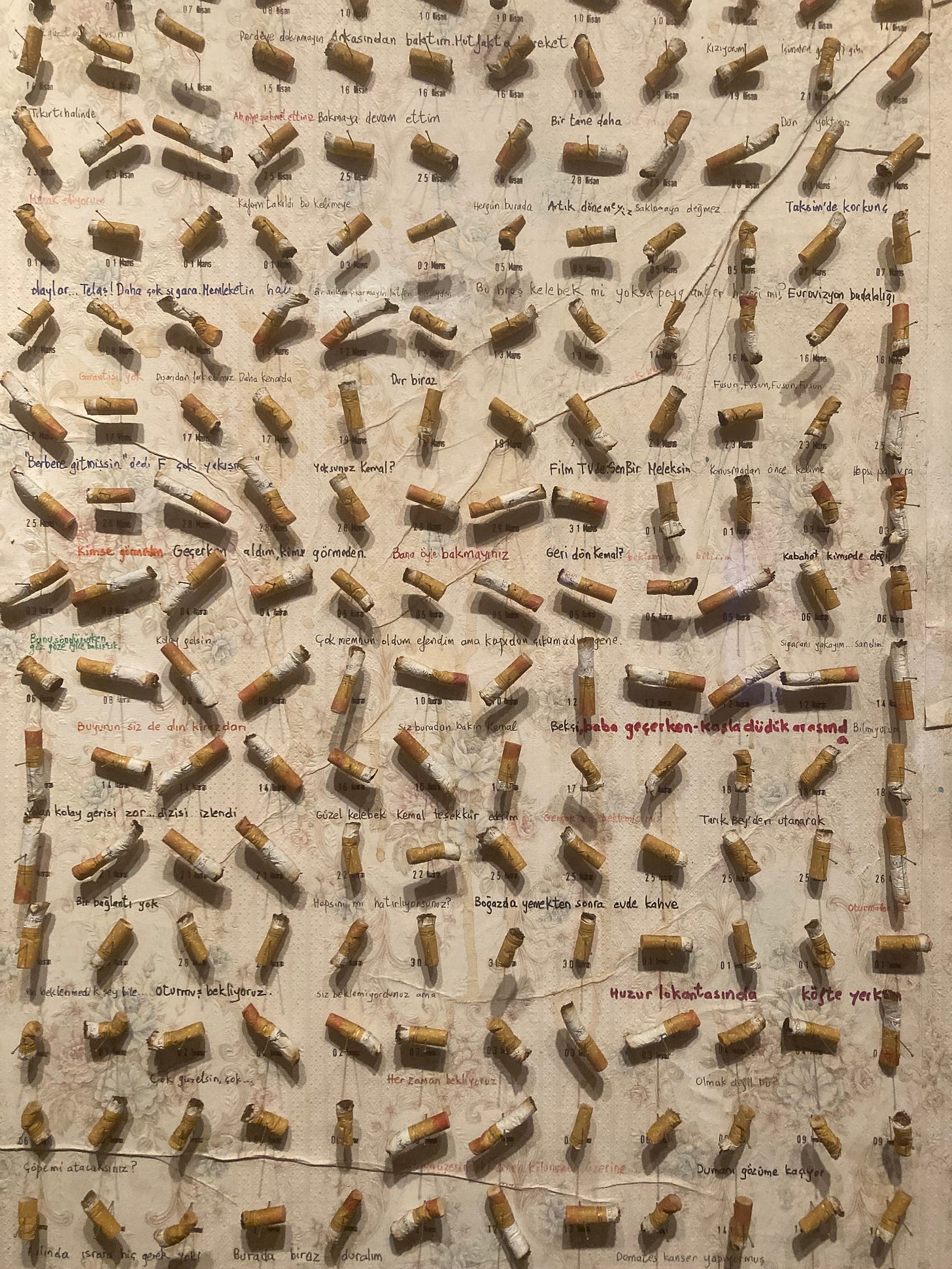

It’s a brilliant idea: In 1975 Istanbul, Kemal falls in love—obsessive, dangerous love—with Füsun. They consummate, but the course of true love never does run smooth. The novel charts the next eight years in which, to quote the blurb, “Kemal becomes a compulsive collector of objects that chronicle his lovelorn progress—amassing a museum that is a map of both society and his heart.” This includes every cigarette end she ever discards, dresses, spoons… you get the idea.

Pamuk follows Kemal’s obsession in excruciating detail and at a certain point in the story I stopped caring. It didn’t help that the book was published in a small-size paperback, 531 pages of, I think, 6 point text which is very hard reading. I’m not recommending the book, in short.

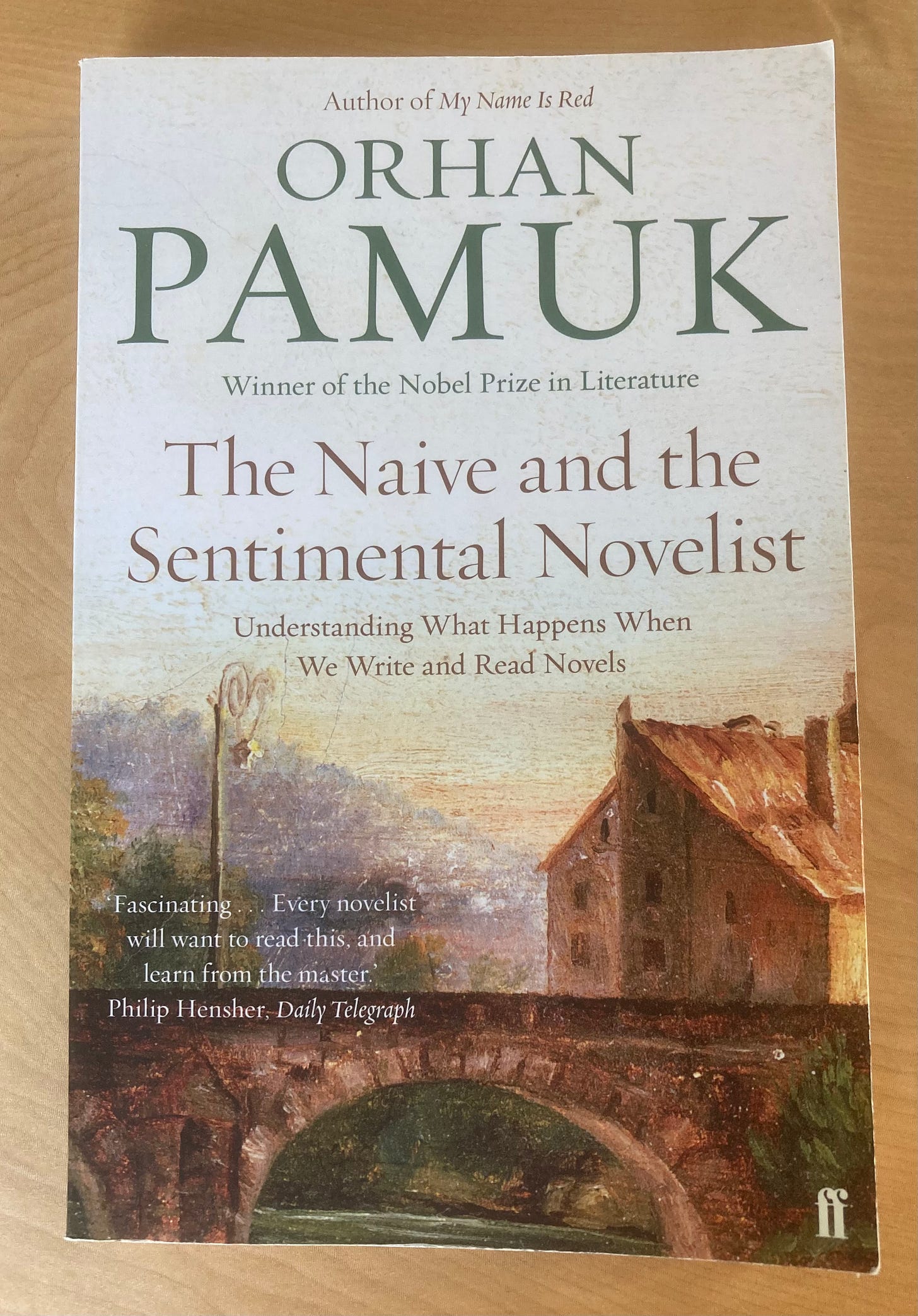

However, as he writes in The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist (an utterly wonderful book I picked up Istanbul, essentially a great novelist writing about the art of novel writing, probably my favourite genre), in the writing of the book, he actually amassed many of the objects Kemal collects. Pamuk, it turns out, is a method writer. He’d find objects in flea markets and think, “Oh, that looks like the kind of necklace Füsun would have worn,” would buy it and put it on his desk while writing that scene. It sounds like this too became an obsession, to the point where he actually commissioned artists to make specific objects for him.

The question then arose once the novel was complete: what to do with these objects? Why, open an actual Museum of Innocence, of course. He bought a house in Beyoğlu, Istanbul (North shore, European side of the Bosphorus - great area, loads of bars and restaurants, including an amazing Iranian place where we had a wonderful lunch) and did exactly that. Needless to say, dear reader, we went.

For someone who had read but wasn’t enamoured of the book, it was interesting. For a novelist interested in the “behind the scenes” of novel writing, it was fascinating. The explanation Pamuk gives (see the photo at the bottom of this page) presents a logical veneer that appealed to the haiku writer in me. For Minori, who is none of the above, it was pretty bizarre. Still, it had made its way into her Japanese guidebook (as a “weird museum by a Nobel winner”) so she was up for it. There’s a level of commitment to the art of novel writing on display that I can respect, and as an exercise in putting your money where your mouth is, it is impressive. If you’ve only got a couple of days in Istanbul it shouldn’t be top of your list unless you are a) a novel geek like me or b) a big Pamuk fan.

The museum shop (love a gift shop) was excellent, with all of his books in (as far as I could tell) every translation. I bought Pamuk’s non-fiction Istanbul (I’d ordered it before the trip but it never arrived), a postcard, and The Black Book (one of the two novels I haven’t read yet). I offered to buy Minori the Japanese My Name is Red but she demurred, wanting to read more about it first.

A few days later, in Cappadocia, I was sat in a beer garden on my own in the afternoon reading The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist (it was my birthday and this, at 44, is how I like to spend my birthday — also it was Minori’s turn with digestive issues so nothing else was going to be happening that day). The waitress brought my second beer (Bomonti Unflitered, a very nice Turkish beer that I enjoyed effusively and repeatedly) and noticed my book.

“Pamuk! He’s so amazing, isn’t he?”

We spent the next ten minutes or so discussing our favourite Pamuk books—she is a literature student working in her summer break—and her plan to go to the museum when she went to Istanbul later this summer.

Reading may be a solitary activity but the bridges that books build between people is something that has warmed my heart my whole life and this was just another small example of that. Cappadocia was gorgeous. We did the obligatory balloon flight and every morning went hiking for 3-4 hours across the lunar landscape, an astounding experience creating unbeatable memories. Yet I’ll also always cherish that brief unexpected conversation between two Pamuk fans: A human connection between two people with little else beyond the customer/server dialectic to connect them. We were, in that moment, part of a community of readers with nothing in common but the fictional worlds in which we’ve travelled.

As I write this the Edinburgh International Book Festival is in full swing and WorldCon (the 82nd World Science Fiction Convention) has just wrapped up in Glasgow. Some of my friends are/were there in a professional capacity, and many more as fans. Insta and Facebook are full of shiny happy people clutching books, lanyards, and drinks, and I have strong FOMO.

I recently delivered a lecture on “what it the point of literature?” aimed at students who are reluctant to read. If I ever do that again (and I will, I’m all about recycling old material) then I’ll include this story. Books aren’t just something you do alone when you should be out playing in the sun. Books are a way of meeting like-minded people wherever you happen to find yourself in the world. It may sound twee or even pathetic to say that having a ten-minute chat with a total stranger about Orhan Pamuk was one of the highlights of my birthday, but if so then I am twee and pathetic. At the end of the day it’s the little moments of happiness that linger in the memory.