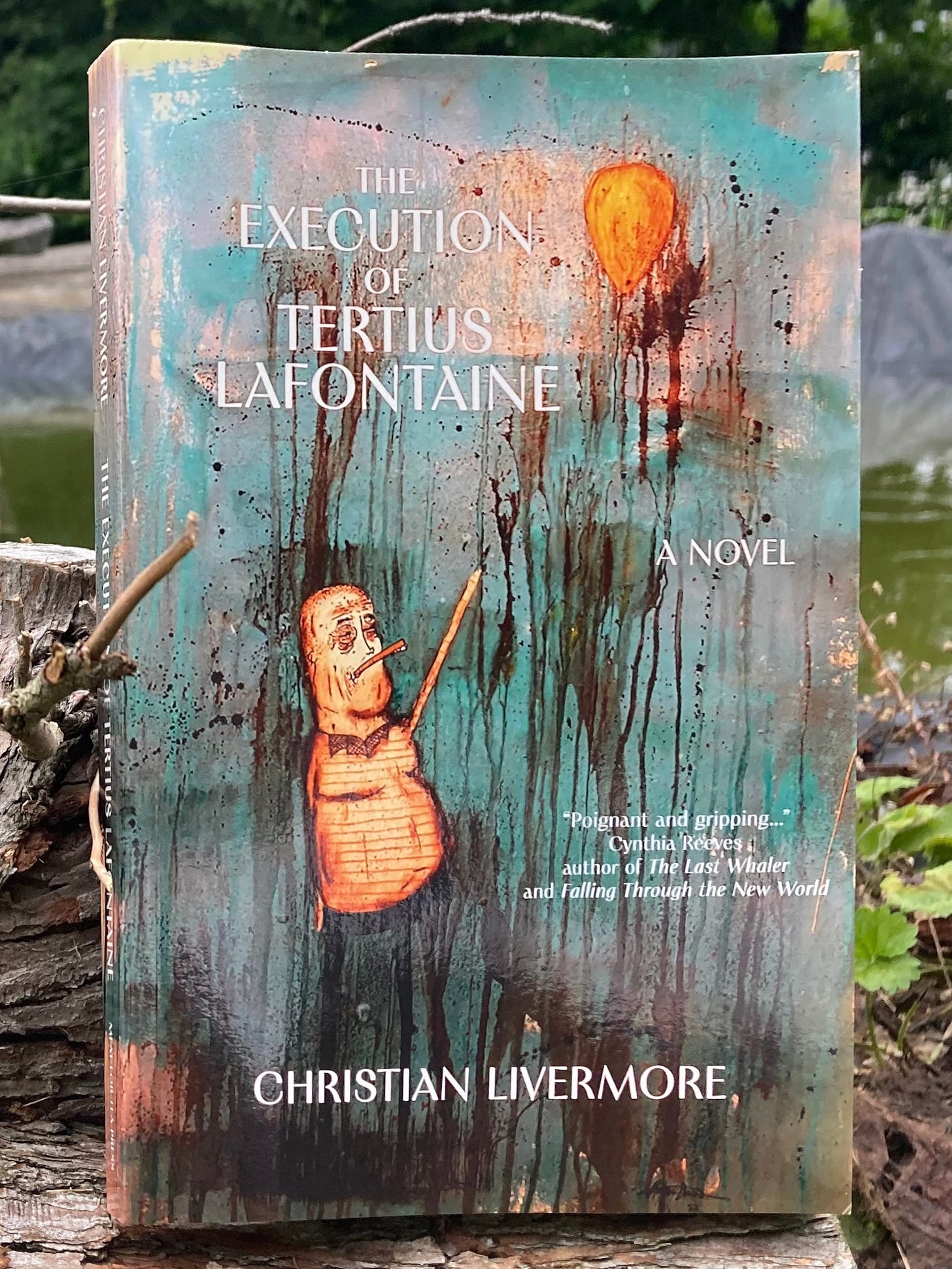

It fills me with huge delight to see this book out in the world. Christian Livermore’s powerful novel tells the story of Tertius Lafontaine, wrongly convicted of killing his wife and sentenced to death in Georgia, USA. It has the depth and scope of an epic packed into only 208 pages, which I find quite astounding. It’s a great read and I recommend it hugely.

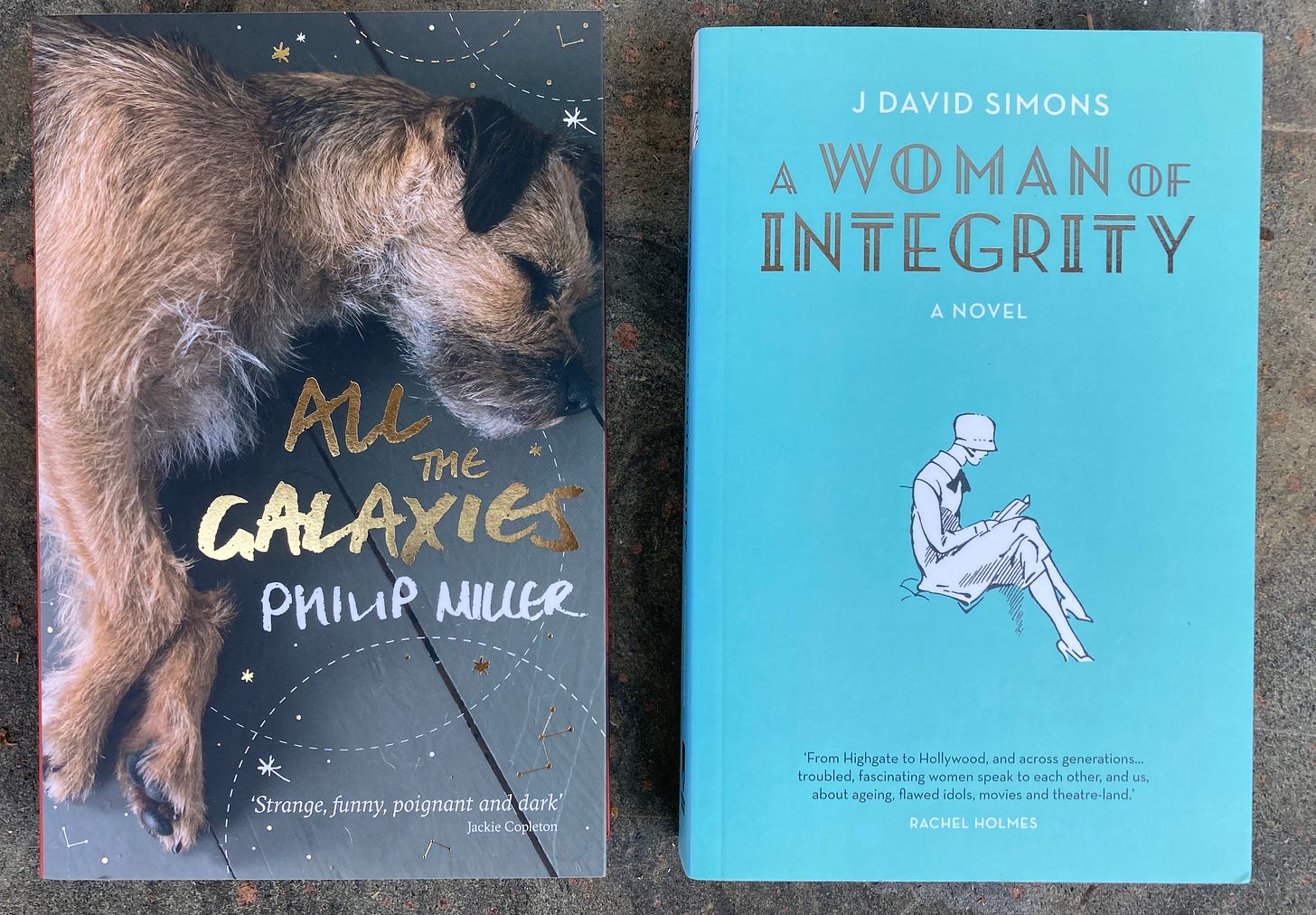

However, the main reason it fills me with delight to hold the paperback in my hands is that I was fortunate enough to work as editor on an earlier version of this book. About a decade ago I worked as an editor for Freight books, the publisher who released my first three novels. It was a wonderful time full of great experiences and I learned so much. I worked on All the Galaxies by Philip Miller (whose new novel, The Diary of Lies is out soon) and A Woman of Integrity by J. David Simons, amongst many others, one of which was The Execution of Tertius Lafontaine.

It wasn’t called that then. I can’t remember what the working title was; no one was happy with it, but none of us could come up with anything better. The Execution of Tertius Lafontaine is the title we were looking for: simple, powerful, sums up the book perfectly. For months I worked with Christian on the novel, getting it into shape (it was mostly there, editing is really about tidying up and seeing the book with a fresher pair of eyes than an exhausted author can). The book was done, ready to go to print. There was a publishing date some time in 2017. I think a cover was done—it was certainly being thought about—when Freight suddenly, shockingly, collapsed. I won’t go into the details of why: I’ve said some things about it before, and I know a lot more, but much of that was told to me in confidence. Also I don’t want to accidentally say the wrong thing and get myself into legal trouble.

It was a shock for me—my three books instantly went out of print (two of them have never come back into print) and I lost my job—but it was a bigger shock for the writers I was working with. When you start out writing the dream, the fantasy, is a book deal, a publishing contract, your book on the shelves in Waterstone’s or your local indie. It’s the goal, the hurdle, the obstacle, the thing you are working towards that you know might never happen. Agents on average get 2000 submissions a year. There are thousands of agents. There are millions of manuscripts out there, right now, many of them good enough to be published, and only a fraction ever will.

You submit for the multi-dozenth time. Your submission gets read. They ask for the full manuscript. The publisher emails back. You talk on Zoom or meet in person. You sign a deal. You receive part of your advance (way less than the media led you to believe). You get an editor. You spend months struggling to rewrite and redraft. You lie awake at night worrying about every page, every word. You fight with your editor over the ending, over the title, over the need for chapter 17. You decide not to include those beautiful song lyrics that really capture the heart of the book because it turns out you have to pay the licensing yourself and they charge more than your advance for a bloody couplet. You hand in the final final final final final draft knowing that there must still be a typo in there somewhere, apprehensive about the joke on page 141, unsure whether the scene in chapter 22 really works, if it’s clear to the reader what you meant by it. You have a print deadline (the final final final final final final time you can make any changes, and there will be changes) and a publication date. You’ve done it. You’ve made it. Your dream is about to come true. In a few months there will be a launch party; your book will be on the shelves and…

Nothing.

In the space of one email, one phone call, you’re back to square one. Your contract is cancelled. You are an unpublished writer with a manuscript. You are going to have to start submitting all over again.

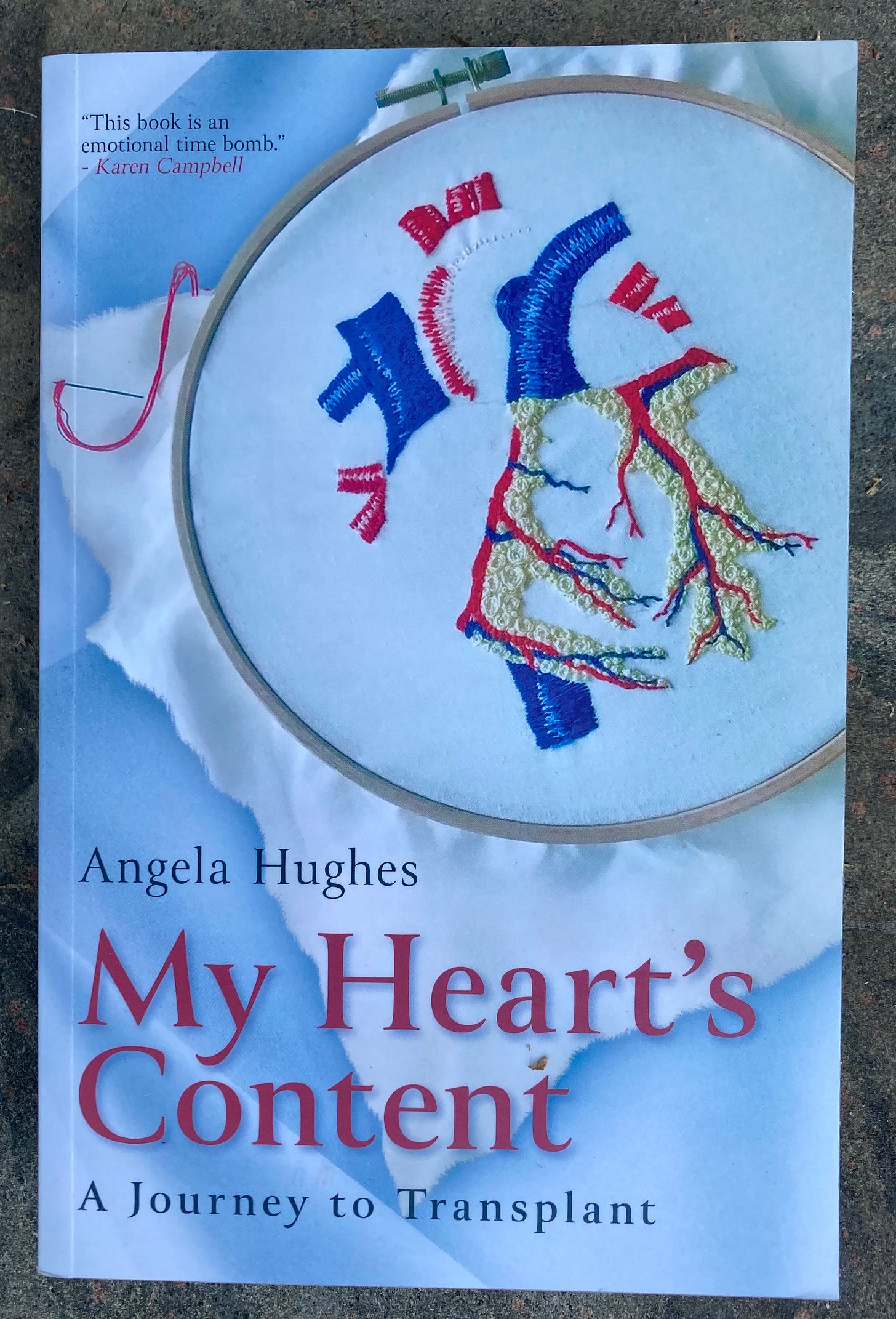

I was working on half a dozen books that this happened to. A few of them were debuts, including Angela Hughes’s memoir My Heart’s Content and Christian Livermore’s The Execution of Tertius Lafontaine. Angela’s book came out in 2020. Christian’s took a bit longer to find its way into the world, but it has now. The other debuts still haven’t been published; nothing by those authors has.

I wasn’t the only editor at Freight. They had debut novelists too. The other books were second novels, fifth novels, books by established authors, a couple of big names. Lots of those books found new homes and came out. Some of those writers are now big fish in the Scottish pond. Some of those already published found a new lease of life, including my own The Waves Burn Bright, recast as In the Shadow of Piper Alpha. But not all of them. So many great books lost, many before they ever had a chance to be read.

Over the years, whenever I’ve had the opportunity, I’ve tried to champion those books. Over pints with publishers, coffee with agents: “Have you come across so-and-so? She’s got an amazing novel, all ready to go.” Writers should always champion each other, support each other, but with these novels it goes further.

I wasn’t involved in the actions that led to the downfall of Freight, was as much of a victim as all the other authors. I too received an email from the administrators offering to sell the stock of my books back to me at a discount insultingly less than the author discount guaranteed in my now void contract but only if I bought every single copy (three novels, a few thousands paperbacks) and picked them up myself from the warehouse in Glasgow. I couldn’t, living in Japan. We suggested they donate them to schools, to libraries, to charities. They were pulped.

I was hurt too, but even so, I felt guilty about these novels. I could imagine all too clearly how destroying it would be to get that near to your dream and have it yanked away. I’d worked so closely with those authors, supported them through crises of confidence, discussed raw emotional topics with them as they tried to turn painful experience into art, even once awkwardly talked through a graphic sex scene, an experience neither of us enjoyed (keep that in mind, novelists, if you write sex scenes: at some point you’re going to have to sit down with your editor and discuss vocabulary choices, phonetic rendering of “sounds”, and the logistics of the scene). I was invested in those novels too. I wanted to hold them in my hands; not as much as the authors did, but still a significant amount. I’m proud of my editing work. I have a shelf with all the books I’ve had a hand in one way or another (edited, written a blurb for, funded through crowdsourcing, put in the hands of a publisher or agent…). I feel like a proud midwife watching the children she helped birth run around the village, the mother having done most of the work but knowing I was there at a crucial moment to make the whole thing a little easier.

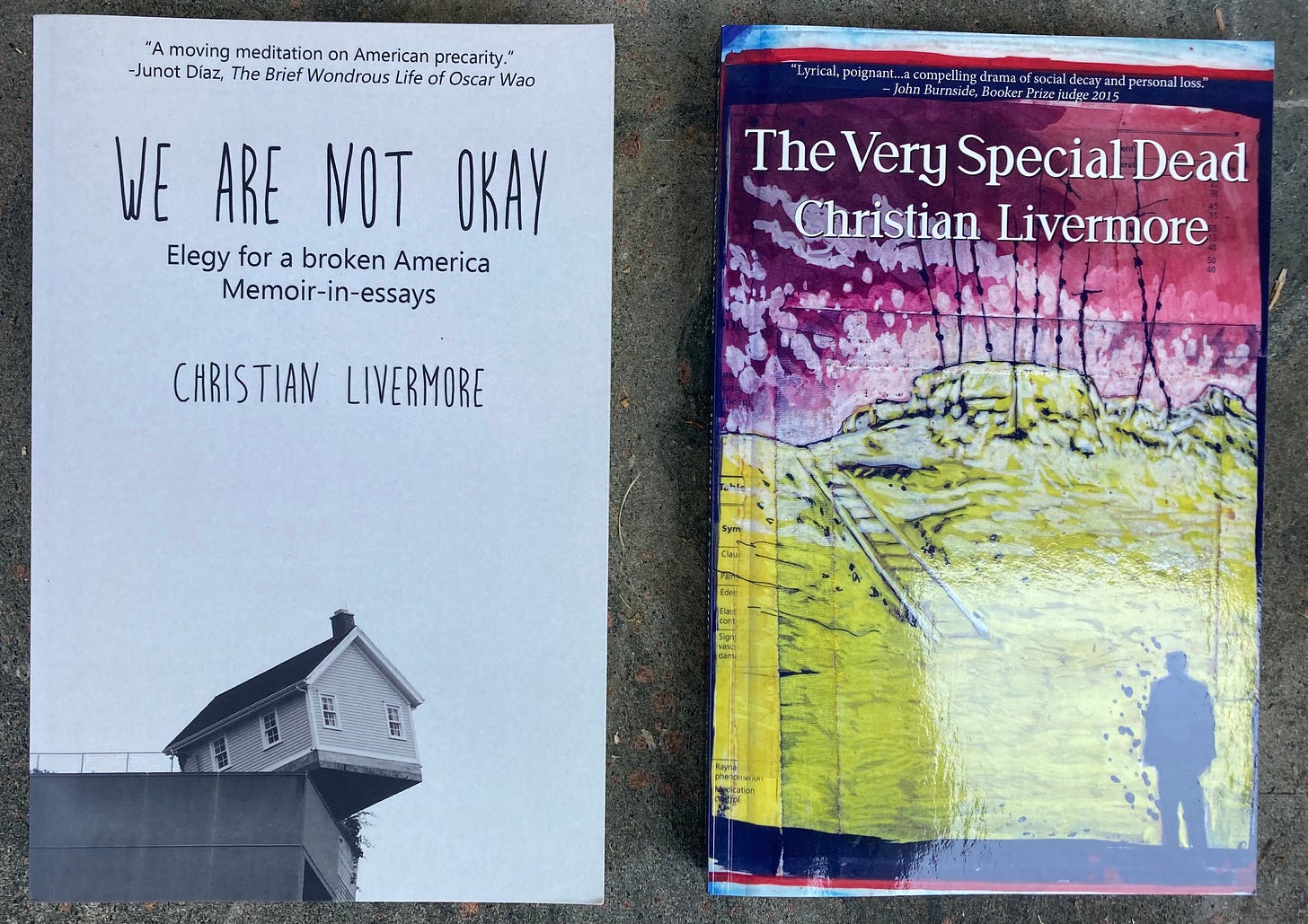

And now The Execution of Tertius Lafontaine can join that shelf. It isn’t Christian’s debut anymore. She’s published We Are Not Okay: Elegy for a broken America, a “memoir-in-essays” and the zombie novel The Very Special Dead, which I called “an exciting new slant on the undead” in my blurb, but for me, this is the very special one. A historical wrong set right. Better late than never, as they say.

As the editor of my first (and so far only) book, you made the process you describe painless. An intuitive editor makes a massive difference, especially for a debut writer!

Great post!