September books

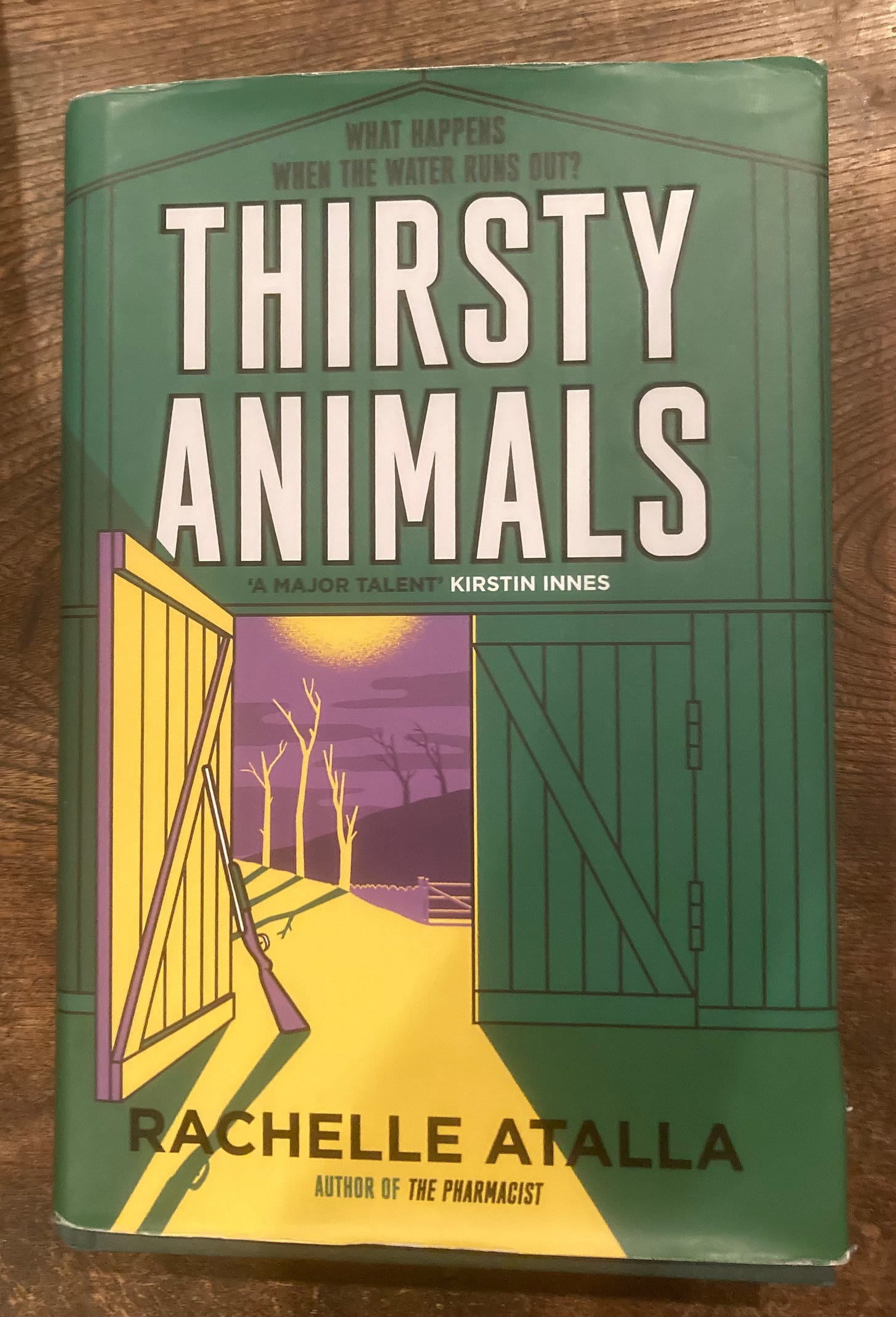

Rachelle Atalla’s first book, The Pharmacist, was one of my top reads of last year and the follow up, Thirsty Animals, is just as good. While the former was a post-apocalyptic nightmare, this one is, if anything, more terrifying. Few SF writers actually go day-by-day through the end of the world: for one thing, it’s a massive feat of imagination, and for another thing, it’s an intensely depressing thought experiment. Atalla does that here, telling the story of a family on a farm in Scotland as a drought hits and the water runs out leading to a complete breakdown of society. It is not a light read, as horror is mounted on horror, but it is a powerful and beautiful book. Like Louise Welsh’s Plague Times trilogy, it’s a little too close for comfort but then that’s always been the point of speculative fiction, hasn’t it?

I don’t think I need to repeat my love of Gutter here and the debt I owe it, I’ve written about it often enough. The new issue is another cracker. Every piece is excellent but the stand-outs for me are Rodge Glass’s essay “On Biography” from his forthcoming book Joshua in the Sky (can’t wait for this), Marta Zanucco’s speculative story “Trial” about the outsourcing of grief, and Lindsay Macgregor’s poem “hence” which is a fascinating puzzle using language in a way I haven’t really encountered before, with the first letter of some words missing such as in opening line “so enderly snow alls”. I’m going to come back to that poem again and again.

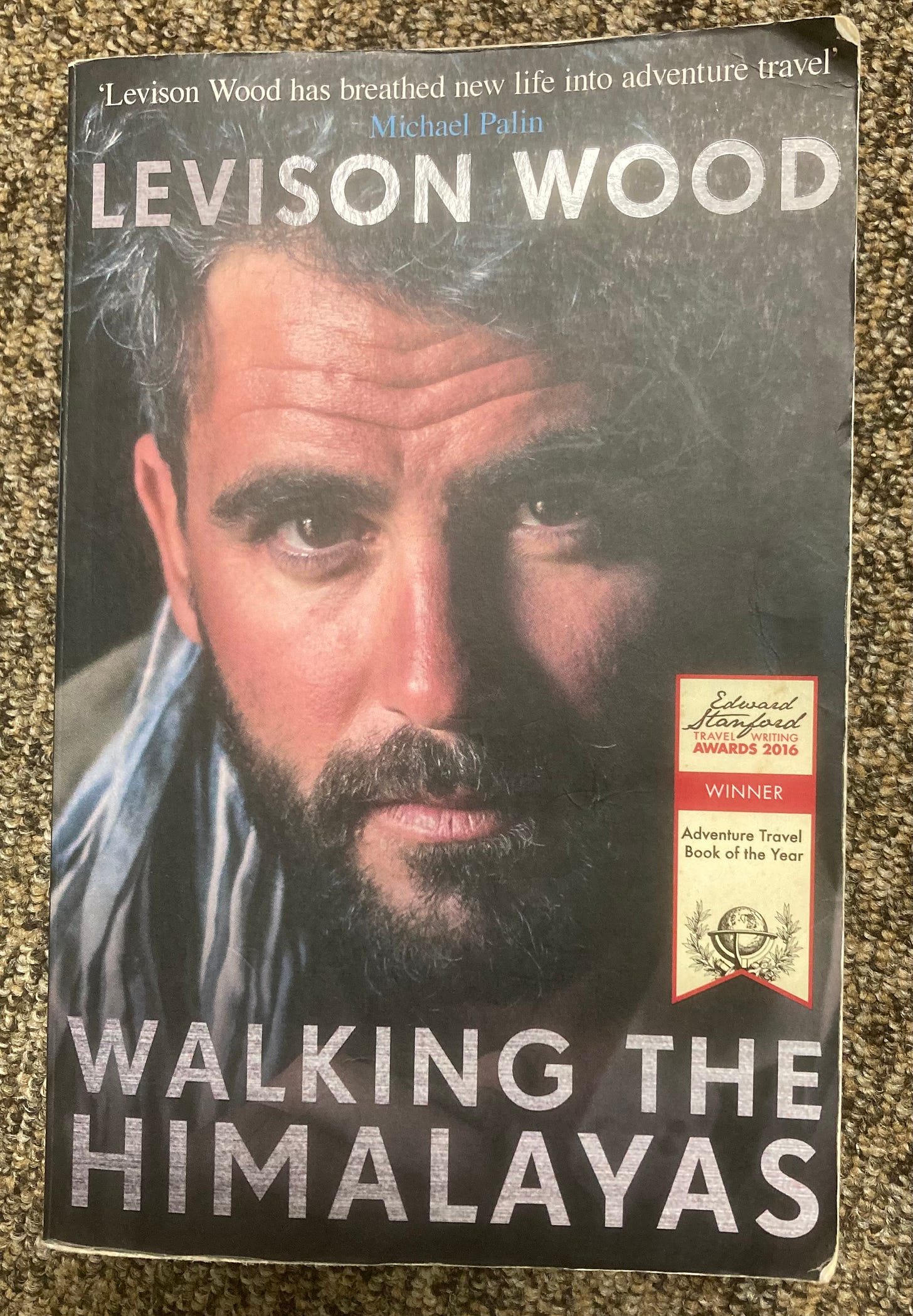

This started well. I was in the mood for some kind of travel writing, preferably about mountains, and I came across this in Arty Bees Books, in Wellington. Praise from Michael Palin, awards: sounds great. It begins well too, the first chapter about being in Nepal when the prime minister is assassinated by Maoists is fantastic. Then… they say never judge a book by its cover but when your book is a travelogue about walking the Himalayas and it’s called Walking the Himalayas, the fact that the cover is a big photo of your face and not, say, the Himalayas, is kind of a red flag. There are some great sections when he focuses on the travel, particularly around a car crash in India, but the author is ex-military, a (literal) flag-waver for Britain’s colonial past, and stereotypically “officer class” (Brits will know exactly what I mean by this) and so the authorial voice is rather off-putting. Travel books only work if you want to travel in the company of the author and in this case, we were far from ideal travelling companions.

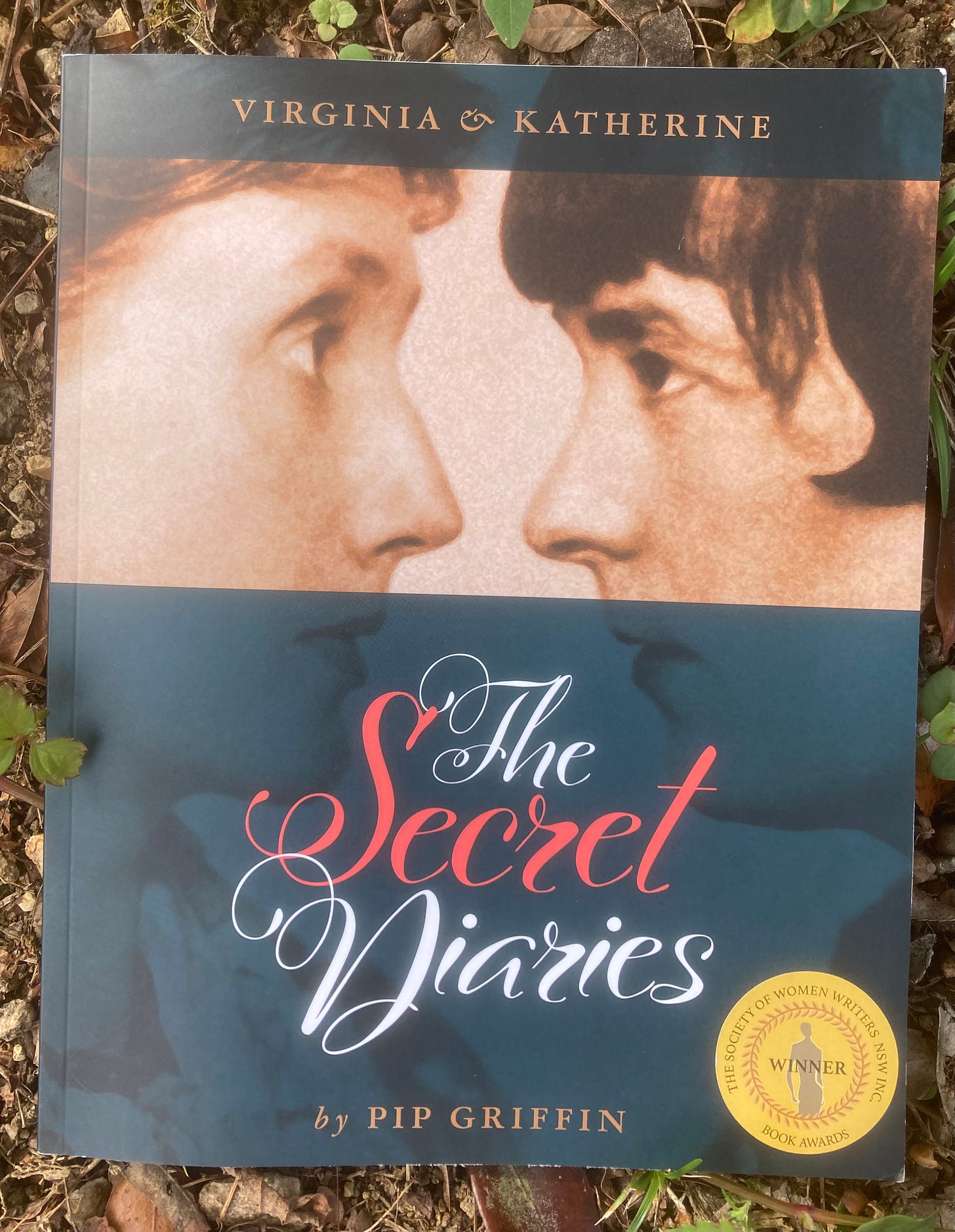

Another book I picked up in Wellington was Pip Griffin’s The Secret Diaries. Wellington was the home of Katherine Mansfield and the house she lived in as a child has become a museum in her honour. We visited it and had a very pleasant afternoon wandering round and chatting to the friendly, knowledgable volunteer who was there that day. I did a class on Mansfield at uni and love her stories, so much so that the books came with me to Japan when I emigrated, though I haven’t read them in years. Mansfield and Virginia Woolf met and became friends, exchanging letters. Griffin imagines the dialogue between them through a sequence of beautiful and moving poems in Woolf and Mansfield’s voices. Griffin—a Wellingtonian—is clearly more Team Mansfield and those poems are richer, deeper, more loving. There are many references that passed me by, not being totally up on the finer details of the biography of either writer (I did read Quentin Bell’s two-volume biography of Woolf but that was about 20 years ago so much has slipped from my mind). Netflix et al really should get on making a series about the Bloomsbury set. So many fascinating characters and stories there.

When I was back in Aberdeen in August I spent a delightful afternoon in the Art Gallery. When I was a student back in the late 90s I spent a lot of time in the gallery and in particular the gift shop which was the only place in Aberdeen you could buy a lot of the literary journals of the day. I encountered things like Poetry Scotland, Cencrastus and Chapman there for the first time and discovered that there was a whole world of writers and readers in Scotland that I could connect with. The gallery shop was also the first place to ever sell one of my books. In 1999 I self-published (grand word for photocopying and stapling) a chapbook of poems called Fences we Build which the gift shop very kindly took and sold. It was mostly work produced through the university Creative Writing Society and fills me with embarrassment today thinking about how juvenile those poems were. When I returned this summer, it was a warm afternoon of nostalgia walking around the remodeled rooms of the gallery and I was particularly pleased to discover that the shop still sells literary journals, in this instance Pushing out the Boat. I’ve been published in POTB in the past and they’ve always been a great outlet for new writers from the northeast of Scotland. A couple of poems by Elizabeth McCarthy in particular grabbed me. I was a touch disappointed to see that when typesetting they seem to double-space after each full stop which ruined my enjoyment of the prose pieces. Why this particular practice still exists in the 21st century baffles me, but it’s a small complaint in the face of the great work they do promoting new writing.

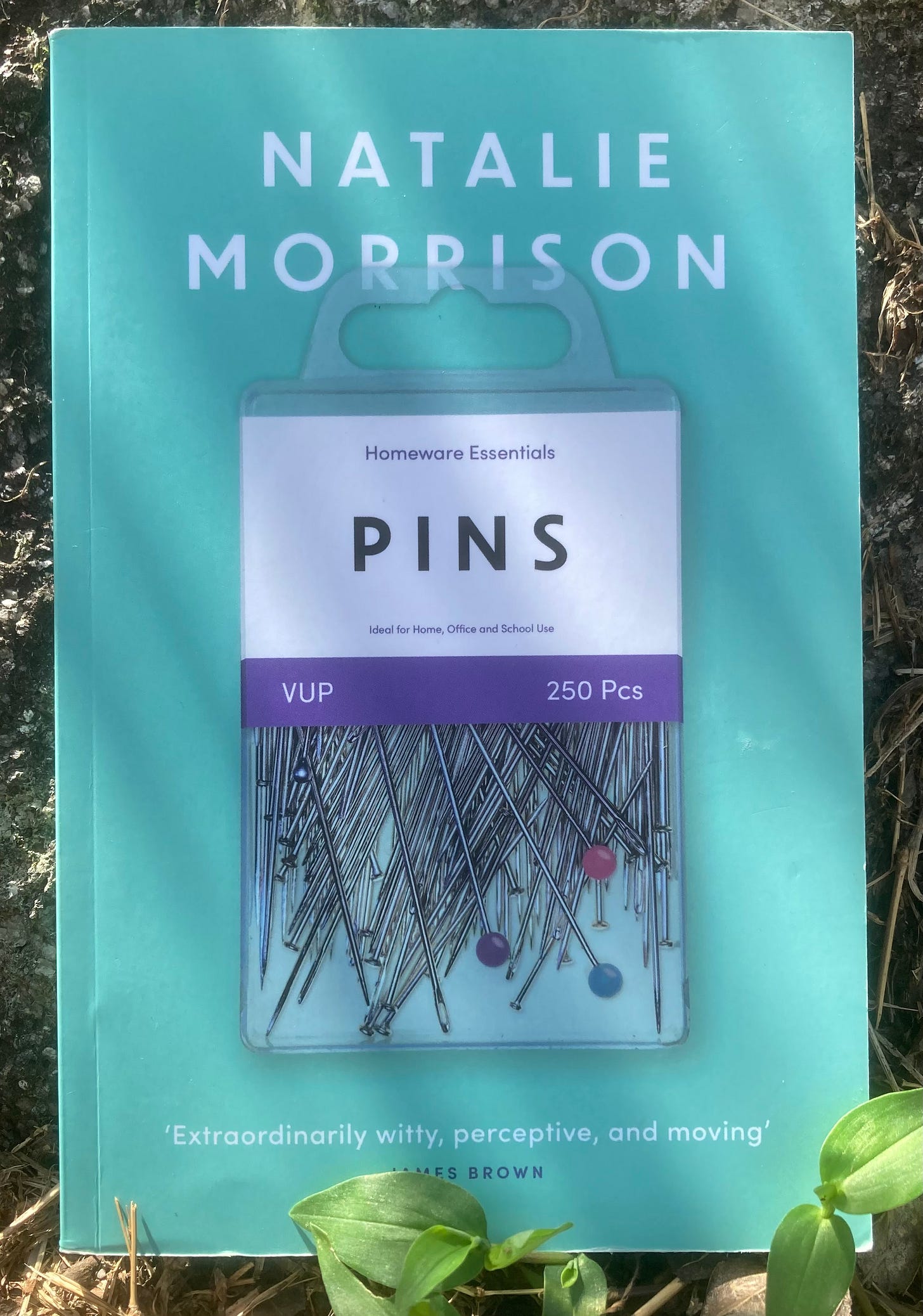

Another book bought in a gallery gift shop, and another book by a Wellingtonian poet but bought in Auckland, Natalie Morrison’s Pins is a wonderful book-length poem about loss and, well, pins. Entirely fictional, the poet assures the reader in the afterword, the book centres around the disappearance of a sister who had an obsession with pins. It’s the kind of trope that would usually only support a poem or two but Morrison finds so many different ways of using the simple image of a pin from pop culture references, through bad puns, to pain and death that it transcends what sounds on paper quite a mundane idea. When I took the book to the counter in the Auckland Art Gallery, the woman behind the till got so animated: “Oh my god that’s such an amazing book, you’re going to love it!” She wasn’t wrong.

I misread the title when I got this as Criticism of the English Novel and assumed it was an analysis of Victorian novels but in fact it’s an overview of literary criticism of the era which is much more interesting. It looked like it might be heavy going but Kenneth Graham (not the Wind in the Willows one) has a pleasant prose style and tucks the odd joke into his thesis. He goes through the different fashions and theories about the novel that developed in the 19th century—realism, anti-realism, naturalism, imagism, romance—and balances them against each other leading the reader inexorably to the conclusion that actually all criticism is really just personal taste (which of course it is). Interestingly there are a huge number of Victorian novelists that Graham references as if they were widely known (and maybe they were in 1965 when this was published) that I have never heard of, which is both a worrying and a comforting thought for a midlist author: today’s trends don’t necessarily reflect the longevity of a book. There’s a lot in here for the academic but also a few things that I would recommend to the budding novelist, particularly the chapter on technique and style. If, like me, you like the analysis of the novel as a form, then this is another good one for the shelf.