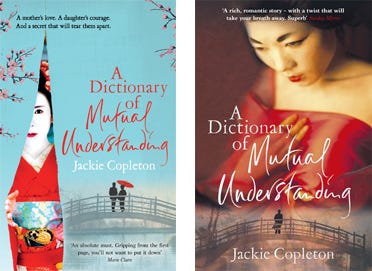

Review: A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding by Jackie Copleton

First published in Gutter 13, Autumn 2015

In 2011, in order to raise money to help the survivors of the Japanese triple disaster, Cargo Publishing brought out A Thousand Cranes, an anthology of Scottish writers. Among the headline names were some emerging writers that are now making bigger waves. One of those is Jackie Copleton, whose debut novel A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding, delivers on the promise of that earlier short story.

Amaterasu Takahashi and her husband Kenzo fled to America in the aftermath of the Nagasaki atomic bombing. Elderly and widowed, she is resigned to a life with only a bottle and regrets for companionship. The arrival of a man who claims to be her dead grandson, Hideo, overturns the barricades she’s built between herself and the past. Her daughter, Yuko, along with Hideo, died on August 9th 1945. Yuko’s husband Shige never made it back from the war. This seems like enough sadness and horror for one life, but we are just getting started. Layers are peeled back to reveal deeper hurts and further wrongs.

The question to which Amaterasu is seeking an answer in those bottles is simple – if I had done things differently, would my daughter still be alive today? The twisted roads that led Yuko to be in Urakami Cathedral – ground zero for the blast – at exactly that moment are contained in the diaries she left behind and in the letters the man who claims to be Hideo carries from his adopted parents.

A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding is a love letter to Nagasaki. The city is something of an oddity in Japan – the open window left when the country closed its doors for hundreds of years – and Copleton’s descriptions endow it with the otherworldly quality Kazuo Ishiguro brought to the city in his early work. Yet mixed in with the sentimentality is an unblinking exploration of Nagasaki’s all too physical sides. She takes us into the filthy underbelly of the ‘floating world’, where women are objects to be enjoyed then cast aside, and where promises last only as long as the sake.

The book takes its title from the snippets of An English Dictionary of Japanese Culture which start each chapter. It’s a clever device that allows Copleton to clarify aspects of Japanese culture readers may be unfamiliar with, but they also act as threads for Amaterasu, breadcrumbs trailing back to a world destroyed by ‘pikadon’ - the onomatopoeic ‘flash bang’.

The details are vivid and vital. There is so much heartbreak in the book, so much anger and regret, that Copleton lets events speak for themselves, allowing her prose to dwell on the sensual realities. From children torturing insects moments before the blast to the prostitutes flashing their red under-kimonos, the novel is alive with vibrant, well-observed moments.

The bombing was a terrible end for millions, but countless others had to live on in the rubble and rebuild. Why me? What if? The past can disconnect us from the future. A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding is about letting go of those questions and finding peace in the absence of answers.