In 2016, after publishing my third novel The Waves Burn Bright, I was asked to write something about planning a book. Some writers plan every detail while others have a direction in mind, or a situation, a character, and let the story unfold naturally. Writers taking their first tentative steps often ask which they should do. Usually it’s writers who don’t plan, and they feel bad, as if they aren’t doing it properly.

I was going to simply repost the original article here but I realised that my opinions have changed over the last seven years, and that this is still a live issue. I work as a freelance editor and the last two edits I’ve done have dealt with issues around planning so the topic has been running about my brain.

To begin with, let’s look at what I said about planning back in 2016:

Yes, I plan. It would be madness not to, but it’s taken me a long time to realise that fact after many years of madness and a huge number of wasted words, wrong turns, and empty hours staring at a mocking cursor.

When I was starting out I was caught in the romantic tractor beam of the Beat Generation. The ghosts of Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs wafted over my desk and drifted through my imagination. The Beats were inseparable from the idea of flowing creativity, of turning on the tap and simply collecting the outpouring: Kerouac’s mythical benzedrine-crazed production of On The Road, battering it out on a single roll of paper in a single sitting; Ginsberg and LSD and those long, lolloping lines that unfold like the breath of the universe being exhaled; Burroughs and his cut-up technique, seemingly the very opposite of planning, taking a Stanley knife through the very notion of organisation. Planning, sitting down with a notebook and saying I’m going to create and it’s going to look like this was directly contradictory to that jazz spirit of improvisation and connecting with something purer and deeper. You don’t open the doors of perception with a blueprint and a protractor. I was an artist, gods dammit, and artists, they... well... they art.

Exactly. They what? The Kerouac thing is a myth. He planned, he thought, he rewrote and edited. To quote from an article on NPR:

‘Kerouac’s brother-in-law and executor, John Sampas, says the three-week story is a kind of self-created myth. “Three weeks” is what Kerouac answered when talk-show host Steve Allen asked how long it took to write On the Road. “And so this gave the impression that Jack just spontaneously wrote this book in three weeks,” Sampas says. “I think what Jack should’ve said was, ‘I typed it up in three weeks.’”

But I bought into the myth and thought, that’s for me! What I refused to admit to myself then was that this adolescent romantic bullshit was masking the real reason for not planning: I was terrified. I wanted to be a writer, I had a burning urge to write but I didn’t know what I wanted to say. Sitting down and planning a poem or a story exposed that, opened me up to the reality that I had no stories, no characters, no voices, just a blank sheet of paper and dreams of Paris and New York and cafes and smoky clubs and my name on spines. I wrote enough to convince myself and others that I was writing. Poems, some of them good, some of them I’m still proud of, got published in respectable places, but there was nothing substantial, nothing to hint at a direction. And the more I smoked and drank and read Plath and Ginsberg and Keats and Bashō, the more I could convince myself that I was a poet, a writer, an artist.

So I recognise the fear in new writers, the “am I doing this right” anxiety. I feel less like that these days; experience has morphed the emotion into something more akin to “there has to be a better way of doing this.” There isn’t. It’s hard. A blank page is a blank page and there’s no short cut to filling it. Someone I edited once said to me when I told them their second draft still wasn’t working and that they needed another pass, “If I’d known it was going to be this hard, I’d never have started.” Yes. We do this not because it’s easy, but because we’re too dumb to admit defeat.

My first published novel First Time Solo (which was the third novel I wrote, the other two, Sometimes Sleep and Dog Mountain remain unpublished) was planned. Not rigidly, but to a fairly-detailed level. It’s set during World War Two and follows a group of men as they go through basic training in the RAF. You can’t wing something like that (pun intended): military training has a specific routine, set goals, exact timeframes. I got hold of my grandfather’s log book (the novel, I stress, isn’t about him, but he was a hugely important resource in the conception and writing of it) and copied out the dates, the locations, the events, the routine. Jack’s timeline in FTS is to the day my grandfather’s timeline in 1943. I had a structure, and I knew there were events I needed to happen so it was a simple matter of mapping them onto the outline. It worked, to a point. It was still difficult, I was still learning to write, but having a spine helped me stay upright. It was, I think, a mixture of the things I’d learned from the previous two attempts and this structural coherence that led Freight to publishing it.

Back to my 2016 essay:

Exhausted after all this I started writing a horror story about a minister who finds a wooden idol in a peat bog and this sparks a witch hunt in a Scottish village. I sat down and just started typing. No plan at all, just the image of the idol and the sense of something horrific about to unfold. I was so happy to be doing something other than World War Two and editing and rewriting and rewriting that the story flowed out of me, genre tropes, bad puns, Hammer Horror dialogue and all. It got to about 30,000 words and ran out of steam. I had no intention of doing anything with it, it was what Virginia Woolf called ‘a writer’s holiday’, a distraction while I wondered what my next serious book should be. But I sent it to my friend Simon Sylvester who said ‘This is great, now stop pissing around and do it properly.’ Suitable castigated I sat down and produced Silma Hill, novel number two.

Silma Hill is essentially entirely unplanned. At a certain point I went back and mapped it all out as an aid when I was editing and redrafting—X happens on Monday, Y on Wednesday, that kind of thing—but planning after the fact isn’t planning, it’s explaining, describing.

Silma Hill has had an interesting life. It is an outlier in my fiction, my only true genre piece other than a couple of SF short stories here and there. It’s not really taken seriously by a lot of people and got some of my harshest reviews (the one in The Skinny which just kept going on about The Cruicible was particularly infuriating: there’s nothing worse than a reviewer who misses the point completely). However it’s the one that seems to have connected with the widest range of readers. It’s the one people keep asking if I’ll ever write a sequel to. For a long time it was the one that had the most positive reviews and reactions on Amazon and Goodreads. It’s the one in which the ending most annoys people and they like to make that annoyance known to me (which makes me very happy. In my fiction I don’t like closure, I don’t like endings. I want my characters to hang out in your imagination after the last page. If my ending has annoyed you, then that’s a job well done).

So, a bind: book one worked because I planned. Book two worked because I went where they spirit took me. What do I do with book three?

That question was taken out of my hands. Silma Hill handed me a two-book deal (the only one of my career so far, something I feel I need to point out to all those SF writers I edit who think that they’ll automatically get a contract for their entire nine-volume series) with a 12-month deadline to delivery of my next book.

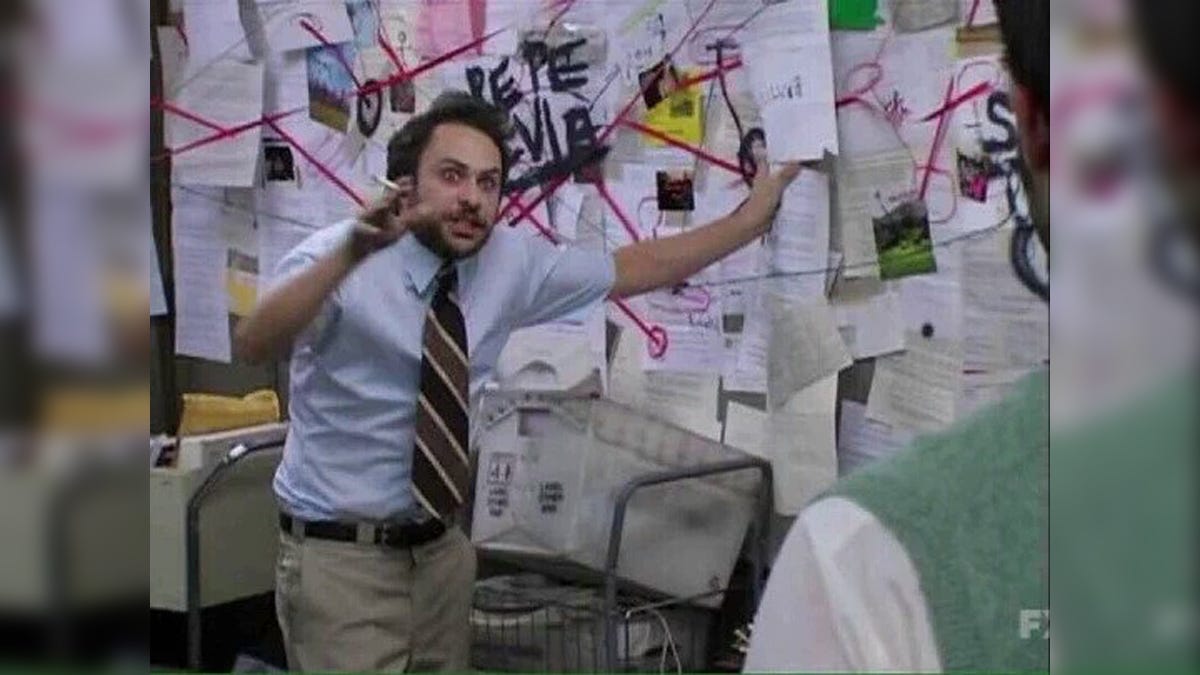

What book? I was on a tight deadline, no ideas, nothing. I couldn’t afford (literally) to wait for inspiration. In conversation with my publisher we hit on the idea of a novel about the Piper Alpha disaster and once I got over my fear of the topic, I got to work. The book takes place over three decades, in multiple countries, with two narrators. Logistically it’s the most ambitious thing I’ve ever done in fiction so you can be damn sure I planned that book. I took over the spare bedroom in our flat and plastered the place in yellow post-it notes that kept falling down in Japan’s summer humidity.

That book nearly broke me: The stress of the deadline, of the topic, writing about a real-life disaster within living memory where survivors and family members are still alive, plus the toll of writing about parental divorce from a teenager’s point of view which brought up so many repressed emotions from my own adolescence. I love that book but I think back to that year writing and editing it and I’m not sure how I got through. One thing that did help: my plan. When I was lost in a tunnel of anxiety and reliving some dark memories, I could still follow the tracks towards the light.

I firmly believe there’s no such thing as writer’s block, just lack of planning. If you are sitting in front of a blank sheet of paper or a computer screen wondering what to write, then there’s little point being there. You aren’t ready to sit down yet. Planning can take place anywhere. I recently moved to a house with a garden. It takes about four hours to cut the grass (not because it’s particularly big but because I’m stunningly inept and have to go over the same patch multiple times. My father-in-law is much quicker) and as I’m unwinding bamboo roots from the rotors and wincing as another stone flies into my shins I’m planning my next book, questions, scenes, conversations playing out to the whine of a two-stroke engine. I have stacks of notebooks with ideas, memos, sentences, diagrams. I’ve been planning this essay for most of the week and I only sat down at my desk this morning because I knew what I wanted to say and how I wanted to say it.

Details. I don’t plan sentence to sentence how the novel will develop but I have notes like, In this chapter he has to find out X, she has to go to Y and the reader has to learn Z about A.

Specific example: The last scene I finished (about 1000 words, the end of part one setting up dramatic opening to part two, 36000 words into the novel), I wrote earlier in my notebook: Tomo is late and Fumio is sent to find him. He’s at the temple sitting with a little campfire on the cliff. He tells his brother about the dreams (and why father is interested in dreams) and asks him to look after Mai if anything happens to him. Fumio agrees and is spooked but doesn’t really understand. When I started writing I knew what I was doing and where I was going. A couple of hours later the scene was drafted. I then went out to cut the grass while thinking How do they react?, What are the press going to say about Tomo? What about Takeda? I know that in about 5000-10000 words my main character needs to confront his father about something big, so the reader needs to be ready to receive the news with him, all the other characters (there are about seven sub-plots, it’s really complicated) need to be in their places so when the confrontation kicks off and the novel moves into act three and charges for the end, everyone’s ready. There are problems, there are difficulties, there are options and alternatives, but there are no blocks. It’s a long and winding road.

You’d never set out on a long journey without having some idea of the destination and at least a vague inkling about how to get there. So far there isn’t a Google Maps for novel writing and Word isn’t fitted with some kind of narrative Sat-Nav, there’s just you and your imagination carving your own route from A to B. That is creativity, pure and deep.

I stand by that, generally. In most cases writer’s block is trying to write before you have something to say. When we’re on deadlines, we sometimes have no choice. When real life gets in the way (kids, jobs, illness) and you can only grab an hour here and there, you have to write. But as I said in 2016, if you’re doing your thinking while doing other things (driving to work, cooking dinner, hanging up the washing) then when you do get your window, the idea is there waiting for you.

Should a writer plan? Yes, absolutely.

Except…

What has changed since I wrote all this in 2016?

Experience.

The Only Gaijin in the Village was unplanned. A series of columns that built a momentum of their own. When I sat down to turn it into a book I had to map out a structure but that was joining pre-existing dots. The Japan Lights was the same. Both were more akin to assembling a collage of chapters than planning and executing a strategy. Life is Elsewhere/Burn your Flags was two characters I had a completely different plan for and which flowed out of me over a weekend (Kerouac style, two days of typing, weeks of editing). My poetry collections—Fractures, Envy the Seasons and my new collection coming out next year—were unplanned. The first two are collections of unrelated work produced up to that point. The new one was an idea conceived halfway through: I have a lot of poems about mountains, maybe I should work towards a collection of mountain poems. My unpublished novel that I’m hawking around right now began as 30,000 words of another project reconceived and the gaps filled in—another join the dots enterprise—and the SF novel I’ve been working on for a few years is very deliberately unplanned, a long-term project that I wanted to do the way I did Silma Hill but with nearly a decade’s more experience behind me. And that, well that’s going very very slowly because I’m a bit blocked on it. No plan. No idea what happens next. I’ve written myself into a couple of corners and I’m not sure how to get out of them.

Basically I learned my lesson in 2016 and then spent the next seven years ignoring that lesson.

In reality, there is no lesson here. Just my own experience. Planning works for some people and for some ideas. Keeping things loose works for other people and other ideas. It turns out I am at my most creative when I have enough of something to see a direction and then begin shaping it, planning where to go next. I need enough of a plan to know exactly what I’m doing the next time I sit at my desk, but I don’t need to minutely plan every single chapter and scene and character arc ahead of time.

As I said, I revisited this old essay and updated it because I’ve been having this conversation with writers I edit recently. Both are science fiction writers with new worlds, epic civilisations, multi-character arcs and (despite the reality of publishing), multi-volume intentions. One is making it up as they go along; the other has meticulously planned everything. Both are struggling and planning is the reason in both cases. One has inconsistencies throughout the book that tear it apart in the end, contradictions that would have been caught in the planning stage, not 90,000 words in; the other is so wedded to their plan that they can’t step outside it and see alternatives, even when it’s the plan that’s at fault because characters that have naturally evolved are being twisted to fit an old conception of who they would be. Both are going to have to rewrite tens of thousands of words to solve these problems.

Should you plan? Yes and no. Both. Neither. It’s Goldilocks: not too much, not too little. Give both a go and see what works for you. Most of drafting is about what you learn about your own writing along the way, lessons that you can use next time. But whatever you do, don’t listen to me. Clearly even I don’t listen to me.