The latest in the Birlinn’s Darkland Tales series—novellas about a moment in Scottish history by some of Scotland’s greatest authors—continues with David Greig’s Columba’s Bones. Each time one of these is published I say it’s the best yet, and I say it again here. Of course that’s recency bias and actually I couldn’t begin to separate them into rank, but it illustrates just how damn good this series is. After a viking raid on Iona seeking the titular bones of St Columba (the man credited/blamed with bringing Christianity to Scotland), a junior monk, a mead wife (woman who makes mead), and one of the vikings left for dead by his crew are all that remain on the island. If that sounds like it sits somewhere between the set up for a sitcom and a tragedy, then you’d be right, and Greig hits both targets dead on. Funny, violent, disgusting, beautiful, heartbreaking… there aren’t enough positive superlatives for this book or the series. More!

I finished it! Finally! It wasn’t easy. I love Orhan Pamuk’s writing and the prose itself is gorgeous but my god he doesn’t half go on. I’d forgotten about this side of Pamuk, my brain focusing on the pleasure of reading things like Snow and My Name is Red and not the huge unrewarding slog that was The Museum of Innocence. I thought this was going to be like My Name is Red but it was more like the latter book. Perhaps it’s another “too big to edit” situation—he is a Nobel laureate after all—but the middle of it is so pointless and flabby I could only continue by either skim reading or by rationing myself to a couple of chapters a night followed by something much more enjoyable. I’d have given up if it wasn’t for the pleasure I’ve had from Pamuk’s books in the past. In fairness, the last 200 pages of the actual story were great, gripping, dramatic and funny in equal measure (I’m not counting the overlong epilogue which was probably the most tedious part of the whole thing). There’s a brilliant 300-page thriller buried in here if you’re prepared to hunt for it. I’d totally recommend Pamuk just not this one.

I struggled with this a little too. I really enjoyed All the Pretty Horses, the first part of the Border Trilogy and this was just as good in places—the first part in particular—but it dragged a bit in the middle. Again, the prose is wonderful and I’m certainly in no position to criticise McCarthy’s writing, it’s more just a question of taste and interest. Long asides, such as the blind man’s tale, didn’t capture my interest and I had to spur myself on to continue. I’ve got part three, Cities of the Plain, so I wasn’t going to abandon it, but I think I’ll let some time elapse before embarking of the last chapter.

This was an advance copy courtesy of the lovely people at New Directions. I’m a big fan of Osamu Dazai so any new translation of his work is cause for celebration. Without going into the whole i-novel genre, Dazai is an incredibly autobiographical author but these short pieces (translated by Ralph McCarthy) take that idea to a whole new level. They are literally self-portraits in which he examines his own life, actions and motives with brutal honesty and frequent self-loathing. They are often hilarious and heartbreaking at the same time. Dazai attempted suicide a few times before succeeding, and he openly writes about these attempts in a chillingly frank way. There’s something about Dazai’s voice, style and outlook that I simply can’t get enough of. Out of all the writers I’d most like to have a drink with, Dazai has to be right up there.

Another poetry collection I picked up at the Japan Writer’s Conference, and another Isobar publication, was Jane Joritz-Nakagawa’s Poems: New & Selected. Jane did two talks at the JWC and because I was hosting I managed to grab only a few minutes of each, but it was enough to convince me to get her book. There’s a wide range of styles and forms on display here, as you’d expect from a career spanning collection. There’s an austere beauty in these poems, and behind them a sharp intellect and a “hardcore feminist” streak (to quote from Eric Selland’s introduction). This is a collection that demands attention and multiple visits, something I am more than happy to give it.

My good friend Taylor sent me an advance PDF of his new book, Visual Poetry of Japan, 1684-2023. It’s coming out in a lush hardback next month and I already have my order in, but it was a joy to get an early sneak-peek. Visual poetry is something I’ve only recently begun to learn about, mainly thanks to Taylor. As one of the founding editors of Tokyo Poetry Journal and the editor of Vou: Visual Poetry Tokio, 1958-1978 (which I reviewed in the Japan Times) on Isobar Press (that name again!) he has been instrumental in making this niche aspect of Japanese poetry much more visible to the ignorant like me. I’m not even going to begin describing the work herein beyond saying that some of it blew me away and some of it confused me, making me want to keep trying to understand until that too blows me away. I even printed out one 1925 piece by Hagiwara Kyojiro and put it up in my office. Profound, powerful, gorgeous stuff.

As some of you know I’ve been a guest on the Def Lep Pod podcast a few times. When I was young Def Leppard were one of my favourite bands. I drifted away from them when grunge came along but things that embed themself in you at an impressionable age remain there forever, and that’s what drew me in to the orbit of the pod, discussing albums that I listened to over and over again on cassette as a pre-adolescent. The official Def Leppard biography, Animal Instinct, was published in 1987 so an updated book about a band that is still touring and releasing music was perhaps a touch overdue. I’d hoped maybe the podcast would do an episode about the new book but sadly Neil has decided to call it a day. I got a copy anyway. This will be of zero interest to anyone who isn’t already a fan of the band but I whiled away an enjoyable Sunday afternoon reliving some of my childhood and being brought up to date with the story.

In something of a dramatic change of pace, I moved from the Def Leppard story to Against the Grain, a selection of essays by Terry Eagleton. Eagleton is someone I first encountered as an undergraduate first during a class on Literary Criticism and then when he did a talk at Aberdeen uni. I returned to his work in 2007/8 when the economy crashed and I started for the first time seriously reading Marxist economics (his book Why Marx was Right was a centrepiece of my reading at that time). A colleague was clearing out their office prior to retirement and I saved a few things from the recycling box, this being among them. Not everything in it was up my street: I have little interest in discussions of structuralism, or analyses of Brecht and Machery, for example, but the essay on “The Revolt of the Reader” was brilliantly executed. Likewise, “Poetry, Pleasure and Politics”, centred around a single line from Yeats, “A terrible beauty is born”, was masterful both in its analysis of why some lines of poetry hit harder than others, but also in dismissive wit. As someone who never really “got” Yeats, this piece of analysis made me laugh loud and hard: “The first reason why [this] line is pleasurable is because it is the last one. After this we can relax, happily freed from further investments of energy.” Amen, brother.

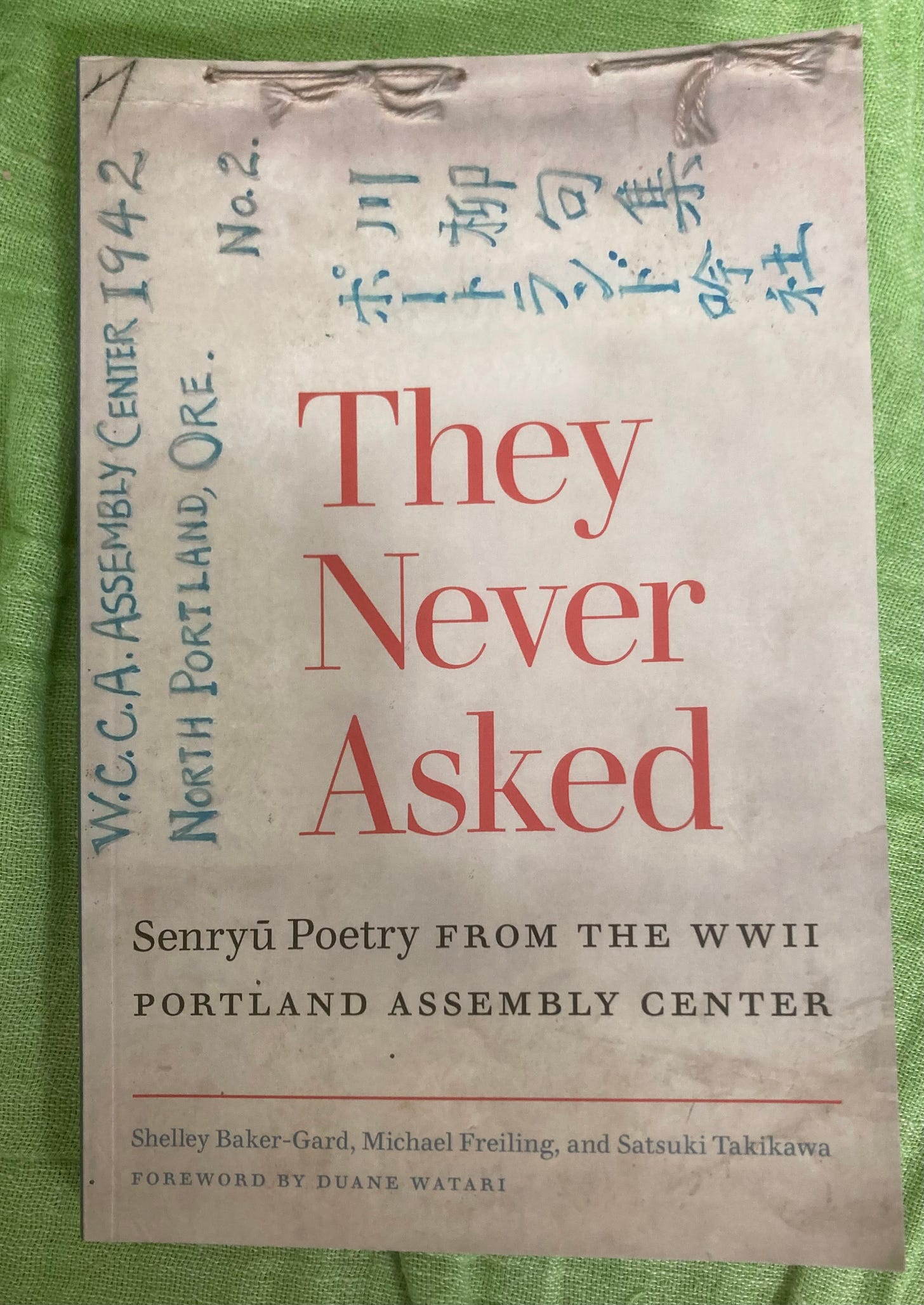

Another poetry book I read this month was this collection of senryū written by Japanese Americans interned during the Second World War. Containing the work of 22 poets, translated into English for the first time, it’s a poignant reminder of what happened to innocent civilians thrown into concentration camps just for being ethnically Japanese. The title comes from the final poem in the book, by Sen Taro: “they never asked us / suspicious or not— / just put us away.” There is a long introduction and afterword that set the poems in historical and psychological context. One paragraph that stopped me dead describes how by 1942 people in America—including those in the camps—knew enough about what was happening to European Jews to draw parallels with their own imprisonment and wonder about their own fate. A chilling thought when you cast aside the benefit of hindsight. On the other hand, more than half the poems here either deal with personal matters outside geopolitics, and a surprising number of them express hope and optimism for the future.

I pulled this out of a pile of books being disposed of by a colleague. Academics spend their career filling their offices with books and paper only to have to empty them out at the end. It’s a sad, sobering sight every year when the boxes pile up along the corridor. I’d never heard of Jenny Diski, which now looks like negligence on my part. She’s mainly known as a novelist but this is ostensibly a travel book; the kind of travel book I write myself, where the travel leads to musings about other things. In this case an expedition to Antarctica is the back drop for Diski coming to terms with her difficult childhood and learning, through her own daughter’s research, what happened to her estranged parents. The prose is sumptuous and Diski had a dark, wry sense of humour, and I’ll certainly seek out more of her books, but in the end I found this disappointing. I wanted much more of Antarctica, somewhere I’d love to visit, and actually there’s very little. Much of the travel sections focus on her interactions with the other tourists on the ship which is often fun but not what I hoped for.

You finished! I am still in the first third of the novel. When did it even get published because I think I bought it as soon as it came out and I’ve been trying to read it for at least a year. It’s good though but you’re right it’s a lot like Museum of innocence.