I got an advance copy of The Hollow Tree direct from the author, and couldn’t wait to get stuck in. Disclaimer, I am very biased when it comes to Phil’s work—we’re friends, our debut novels were published by the same publisher, and I was the editor for his second novel, the criminally out of print All the Galaxies—but I’m also not really a big fan of crime fiction so I think one cancels out the other and I can be at least partially objective. On the surface, this is crime fiction: Cynical Scottish journalist Shona Sandison investigates mysteries and crimes. There’s the usual violence, humour and profound personality problems that are standard tropes in the genre. Where Phil gets interesting is that there’s always something weirder going on under the surface. Here it’s ouija boards, instructions from beyond the grave, and Tory MPs up to their necks in what tabloids would lazily label Satanism. Crime fiction is so ubiquitous these days that I’m always amazed when a new writer manages to carve out a niche for themselves and Phil has definitely done that here. Phil asked for a blurb (quote for publicity) which I was very happy to give: The Hollow Tree confirms Philip Miller as a powerful and unique voice in the crime fiction landscape, carving out a niche for himself at the boundaries of crime and horror. In his stories there is always much more going on than can be seen with the naked eye, and it takes a special investigative mind like Shona Sandison's to uncover the truth. In Sandison's third outing it's clear that Miller has just scratched the surface of his compelling journalist which augurs well for the future: more of Shona Sandison's adventures, please. Much, much more.

Another ARC, this time from Honford Star. Cannibals is a very short book and a bizarre one. A bit like Phil’s novel, it straddles the line between realism and something much more unsettling (not magical realism, a term misused to mean anything from “weird” to “science fiction”). Set in 1988 in a slum community on an unnamed riverbank (it feels like Tokyo or Osaka but maybe that’s my prejudice about their filthy rivers), the protagonist is Toma, a teenage boy from a spectacularly broken home whose greatest fear is that he will turn into a violent abuser like his father, something that seems almost inevitable. This is not for the fainthearted and should perhaps come with trigger warnings although the list would be endless: if you’re triggered by certain unpleasant things, there’s a good chance they’ll crop up over the course of these 82 pages.

A new translation by Mark Gibeau of what was previous published as No Longer Human. I love Dazai but I have to say I’m not as partial to this book as others seem to be; it’s his most popular in translation. It’s excellent of course, but it lacks some of the humour and dark playfulness that many of his other stories exhibit. It’s hardly surprising really, as he killed himself not long after finishing it. It runs over some of the same tropes Dazai kept returning to, particularly his first suicide attempt, and it’s hard not to read it as a summary of his attitude towards his own life. Of course, there is some discussion as to whether he really meant to kill himself—he’d tried and a couple of times failed before (always with a woman in tow who were never as lucky) and seemed more fascinated with the concept than really desperate to die—and he’d planned a further novel called “Goodbye.” There’s a third translation of this in the works (the first was by Donald Keene, the new one is apparently by Juliet Winters Carpenter) but while not all of his works are available in English, I’d rather publishers focused on them first.

ARC ahoy, this from Reaktion Books. Basically I felt guilty about not getting to some of the books I’d been sent so I used the relatively free time of March to catch up. With the new adaptation of Shōgun on the box, this timely biography of the real-life inspiration behind the Clavell’s fiction is worth checking out. There’s a lot of context setting, drawing the geopolitical maps of the 1600s into which Englishman William Adams and the Dutch East India Company sail, and quite a lot of the book concerns the nitty-gritty of early modern free trade in Asia, but Cryns has a soft style that helps the necessary framework go down as easily as Adams’s scarcely believable adventures. Not as rollicking as Clavell’s novel but then this is real life which rarely does. Particular high points are the pathetic ways in which European Christians fight like spolied children in front of Tokugawa Ieyasu and his son. In histories of Asia, European Christians rarely come out of it looking good and that’s the case here. Definitely worth checking out, as is the new TV series on which Cryns worked as an advisor. I’ll be interviewing him for the Japan Times, so keep an eye out for that.

Another ARC. I remember being an undergrad, talking to someone who reviewed for one of the Scottish papers and thinking that a job where you get free books sent to you would be the greatest thing. You know what? It is. Christopher Green is based in Tokyo and has written children’s books; Takeout Sushi is his debut short story collection (on Neem Tree Press). He sent it to me in the hope of a blurb which, upon reading, I was very happy to give: The stories in Takeout Sushi are a delight, witty and smart, the voice clear and direct, the imagination rampant. Green has an eye for the telling detail and a way of looking at the world reminiscent of Roald Dahl at his most mischievous. A brilliant collection.

Polly Barton’s translation of Mieko Kanai’s Mild Vertigo was sent to me by New Directions. It’s something of a stream of consciousness novel in the domestic existentialism mould of Yuko Tsushima, where the protagonist—a housewife and mother in Tokyo—struggles to find meaning for herself in the maelstrom of daily life. I prefer Tsushima’s take on this genre; she has a drier wit that appeals more to me. Also the stream of consciousness tsunami of everyday detail can be hard to wade through after a while. Kanai is a key writer in Japanese literature and the stories she tells are important, but on a purely personal level, this didn’t do the job for me.

Another ARC that wasn’t my bag was Takaoka’s Travels by Tastuhiko Shibusawa. This was an electronic ARC from Stone Bridge Press. I’m a big fan of that publisher and I’ve given glowing reviews to many of their publications, but this just wasn’t for me. Set in the ninth century, it’s one of those travelling-in-Asia fantasies with fantastic beasts and magical kingdoms of the Journey to the West variety. I’ve never really been into them (no specific reason, just never enjoyed them) and whatever tenuous interest I had was killed off by Umberto Eco’s brilliant pastiche Baudolino. Now reading this kind of story is like trying to watch a serious thriller about a plane crash after watching Airplane!

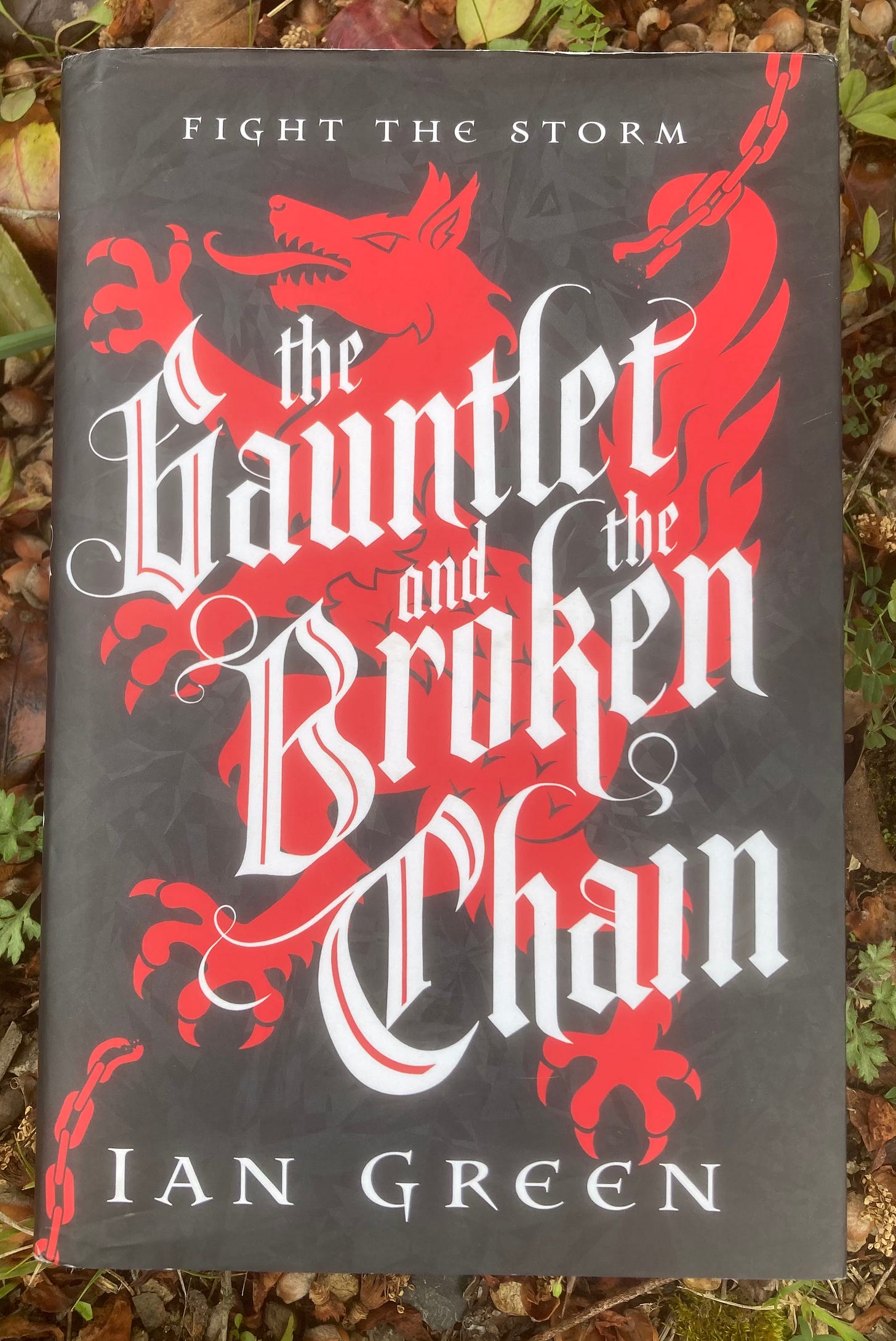

The month ended with a bit of escapism that is much more in my wheelhouse. The Gauntlet and the Broken Chain is the final book in Green’s fantasy Rotstorm trilogy. It’s been a great series and I’m fascinated to see where Green goes next. I’ll probably re-read this trilogy before too long because the level of detail and plotting is such that I know I’ve missed things. That was exacerbated by the gaps between reading each installment. A plea to writers and publishers of these kinds of epic serials: please provide a proper “previously on…” at the start of the book. At least a year—often more—will pass between us reading installments and few of us have the time to re-read parts 1 and 2 before launching into part 3 (however much we’d like to). It would save a lot of “wait, who was that? How are they connected to them?” which really slows down the process of getting back into the world and the story.

I've really enjoyed Ian Green's work, too. Although I've yet to buy the next two books in his series (something I should change rather soon).

As an aside: would it be possible to send you an email, Iain? I have some questions regarding being a teacher in Japan. Thank you! :)