March Reads

March was an eclectic month reading-wise. I didn’t think I was going to get much done as my work plate overfloweth but it turned out I needed that down time in the evenings to de-stress, and reading on the sofa after dinner is one of life’s great joys.

This was helped by some great storytelling from two great crime writers. David Peace’s Tokyo Redux had been on my shelf since the day of publication but as with so many books I buy, I waited until I could take a clear run at it. I am a huge fan of David Peace and when he’s at this best I don’t want to look up from the page, however he can also be a difficult writer and at those moments being interrupted every few pages doesn’t help. Fortunately this is one of his best and easiest to read. The third part of his Tokyo trilogy (only a trilogy in that it’s the third book he’s written set during the US occupation of Japan) based on a true crime, in this case the Shimoyama murder. It’s truly excellent, all the things I love most about Peace and none of the stuff that turns me off, and a perfect example of how foreigners can write about Japan while avoiding all the cliched nonsense that usually hitches a ride. Great stuff.

The other crime thriller was Liam McIlvanney’s The Heretic, book two in his Duncan McCormack series (after The Quaker). Cards on the table, Liam is a friend so I wouldn’t be on here saying bad things about this book, but nor would I praise it unduly (writers, if your friends keep telling you they haven’t got round to your book yet, it usually means they have and didn’t like it) but this is excellent. Appearances in this post aside, crime isn’t really my genre (it’s about the only genre I’ve never tried writing in which for those who’ve followed my twists and turns says a lot) but both of the Duncan McCormack books have me hooked.

Another one long on the shelf was The Mountains Sing by Nguyễn Phan Quến Mai, the story of three generations of a family surviving Vietnam’s horrific 20th century. I came across this via a tweet by Viet Thanh Nguyen, whose books I adore, and it didn’t disappoint. By page 50 I was crying, and by the end I was a mess, yet given the subject matter and story it is strangely uplifting, a book that quietly extolls the virtues of forgiveness, a quality all too lacking in today’s discourse.

I managed to get hold of another Per Olov Enquist novel in translation, this time March of the Musicians (translated by Jane Tate). Most of his books in English are out of print so this is starting to be something of a treasure hunt. In this case, it’s easy to see why. The story is good, and the writing excellent, but it doesn’t soar like the others I’ve read, and sometimes reads more like a writer trying to find their groove but not always hitting it. From a historical fiction point of view, the story of grassroots socialism in late 19th and early 20th century Sweden is fascinating, not least the Stockholm (ha!) syndrome employers utilised to turn workers against each other, but this isn’t the Enquist book I would suggest people try first. It isn’t helped by the state of the text, clearly unproofed, and the translator’s decision to render rural Swedish dialect as a mock-Yorkshire, all up t’mill and that. Disappointing.

Far more satisfying was Solo Dance by Li Kotomi (translated by Arthur Reiji Morris). I was lucky enough to get an advance proof via Morris, with a view to reviewing it for Japan Times but someone pitched it before me. Li is from Taiwan but writes in Japanese and won the Akutagawa Prize last year (for a different book, as yet untranslated though Minori tells me it’s excellent). Li writes about LGBTQ+ experiences in Japan, a very underrepresented topic, particularly in translation, and this is a book that is both uplifting and utterly depressing in equal measure, but which deserves a huge audience.

I also got an advance copy of Longing and other Stories by Jun-ichiro Tanizaki (translated by Anthony H. Chambers & Paul McCarthy). This collection of three longish short stories are themed around dysfunctional families and “bad” sons in particular. Tanizaki is one of Japan’s great 20th century writers, known primarily for dealing with issues of class in the first half of the century, and these stories highlight the range of his talent as well as his humour: the second story, “Sorrows of a Heretic” is a dark satire that had me laughing aloud at the end. Not necessarily the place to start with Tanizaki but a welcome addition to the shelf.

Talking of deserving a huge audience, the new issue of Gutter (25) hit my doormat. I have an essay in it about creativity and depression, and there are great pieces by some of my favourite Scottish writers, but the stand out selection for me was Deborah Chu’s “some solicited advice for surviving the acqua alta,” a stunning piece of writing, structurally challenging, lyrical and powerful. This is why I love Gutter and have done since it started - it never fails to introduce me to amazing writers.

In the same envelope, Gutter co-editor Henry Bell had very kindly slipped in his two poetry chapbooks, The Inner Circle and The Last Lochan. I know Henry’s writing mainly from his biography John McLean: Hero of Red Clydeside but he is also an excellent poet. The Inner Circle is a collection of poems about Glasgow, and the opening poem “Brand New” I’ve been sharing with everyone since I first read it. Liz Lochhead describes Henry as “one of the finest young poets in this country” and I never want to find myself disagreeing with Liz Lochhead.

The Last Lochan covers many of the same themes - Scotland, climate change, the failures of capitalism, but all from a very personal, emotional place summed up by the line “on the day we destroyed the world I ate a peach.” Bell’s themes resonate with me, his structures and his choice of words make me return to his poems again and again. Besides, any poet who writes about punching fascists is my kind of poet.

March was a big month for non-fiction. The Long War for Britannia 367-644: Arthur and the History of Post-Roman Britain by Edwin Pace was an unlooked for review copy (thank you!) that I thoroughly enjoyed. Pace picks apart the myths of the supposed “dark ages” to create a thrilling narrative of societal change with lashings of battles. It sometimes dwells too long on the historiography for the casual reader (of which I am certainly one), and the reference to Arthur in the title is somewhat misleading since he doesn’t appear until the very end (I suspect this was a marketing decision rather than an editorial one) but it filled in an enormous number of blanks in my knowledge of early British development. Could’ve been a few more Scots in it, of course.

Speaking of filling in blanks, I also finished Tim Pat Coogan’s exhaustive history of The IRA which I’d been reading on and off for a while. I’d read a lot about the early days (1916 in particular) and lived through much of the latter days, but I knew nothing about how the story got from the end of the Civil War to the Troubles. This book more than told me. At 800+ pages it’s daunting, and the level of detail is sometimes so granular as to lose me completely, but it is the book on the subject.

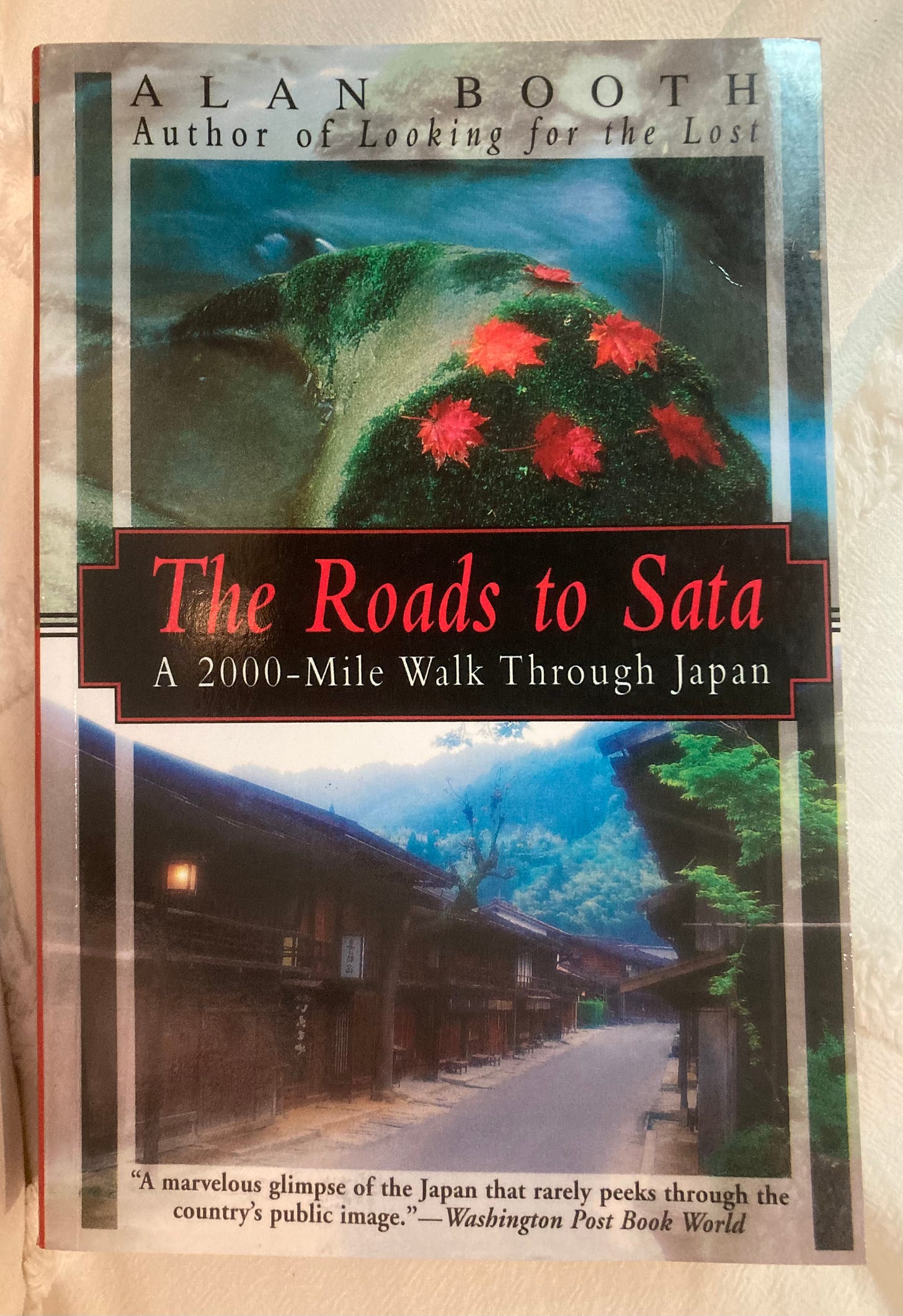

On a much, much lighter note I read The Roads to Sata: A 2000-mile Walk Through Japan by Alan Booth. Having just been to Sata (the southern tip of Kyushu) and being a fan of other travel through Japan books (obvs.) I was looking forward to this but honestly… there were good anecdotes, and the simple fact that he walked the whole of Japan is impressive, but the story lacked any emotional or psychological depth (still have no idea why he bothered, which is surely the real story) and since it was published in 1985, is very much of its time, both in the language used and in the portrayal of the Japanese people he encountered (rough synopsis: the longer he walks, the tireder he gets; the tireder he gets, the more people piss him off).

A much better book about life in Japan was Amy Chavez’s The Widow, The Priest and the Octopus Hunter: Discovering a Lost Way of Life on a Secluded Japanese Island. Amy and I are appearing on a podcast together later this month so I got an early copy. She lives on a small island in the Seto Inland Sea and interviewed many of the residents to build up a fascinating picture of the community. It’s beautifully written, evocative, moving and funny in equal measures and I can’t wait to chat to her about it. In many ways it’s the flipside of my own book: a foreigner moving to a rural community but while mine is centred around my own experiences, hers is more outward looking - they make a great pair.