I spent the last week of February in Hawaii, which was wonderful, and came back to a few books on my doorstep, including this very lovely thing. Gutter 27 was the perfect accompaniment to severe jet lag, and kept me fully entertained when I woke up at 2:30am a couple of mornings in a row. As always it’s packed with great new writing, though the stand-out piece for me this time was probably “What Kind of Girl Are You?” by Nicola Rose. I’m jealous of writers who can manipulate the short story form at will, because it’s always been beyond me. I can tell a story, but while I see endless possibilities in the multi-dimensional tesseract that is the novel form, the short story is a different beast entirely. Rose takes the structure of one of those multiple choices quizzes in lifestyle magazines and uses it to tell a profound and powerful story of identity. This is why I love Gutter.

When I was in Hawaii (did I mention I went to Hawaii?) I stopped by Da Shop, an indie bookstore that specialises in Hawaiian literature in its various forms (not exclusively, but mainly). I know nothing about Hawaiian literature so I spent a delightful hour or so picking up everything, reading the blurbs and, in some cases, literally judging by the covers. I left with a stack of diverse, exciting-looking and, crucially, brand-new-to-me books. When I put my stack on the counter the young woman on the till looked at them and said, “good choices,” which was the cherry on top. One book was this collection by bell hooks. She wasn’t Hawaiian, but was rather a Black woman from Kentucky who published an intimidating number of books, mostly on feminism, gender, and racism. This collection of poetry about her roots in the “backwoods” of Kentucky and the legacy of slavery, colonialism, capitalism, and white supremacy is one of those poetry collections I’m going to be returning to again and again, as every line needs to be meditated on. I’m also going to explore hooks’s work more deeply since I have, until now, been ignorant of her output and it seems both brilliant and important.

For a generation of Scots, The Sopranos will always be an Alan Warner novel first, and some imported gangster soap opera second. We recently watched and loved the film adaptation, Our Ladies, which took its sweet time making it to streaming services in Japan, and it was only then that I realised Warner had written a sequel, The Stars in the Bright Sky. Sadly it’s not quite as good as the first book. The writing is still excellent, and the banter between the women is often hilarious, but it feels a bit flabby, and the premise—that their holiday abroad is endlessly delayed—means that for most of the book nothing happens. It picks up a lot in the last third, and the ending is a poignant piece of structuring, but I don’t think I’ll be revisiting this in the future.

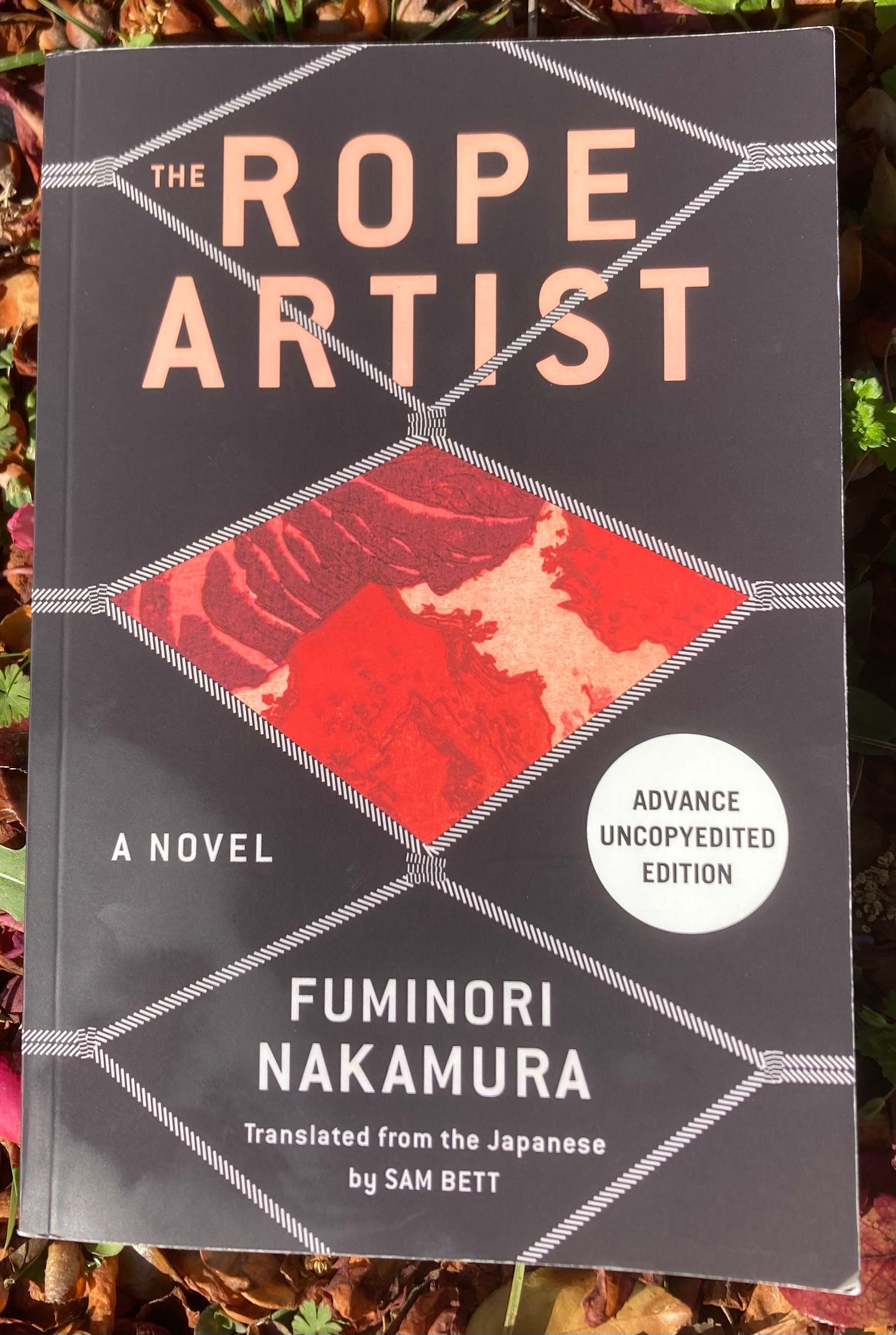

This month’s advance copy was The Rope Artist by Fuminori Nakamura, translated by Sam Bett. Another one I’ll be writing about in more depth for the Japan Times, but if you’re a Nakamura fan, this is definitely one of his strongest. Playing with noir tropes, it reads from the start like a police procedural but nothing is ever as it seems with Nakamura. While he always writes about the darker sides of Japanese society, this delve into the knotty world of BDSM and kinbaku (rope-tying) is incredibly NSFW. Dark, twisted, and brilliantly written.

Another literary journal, this time issue 3 of Monkey: New Writing from Japan. While any new publication of Japanese literature in translation is cause for celebration, and new stories from Hiroko Oyamada, Hiromi Kawakami and Mieko Kawakami raises the party a notch or two, I was underwhelmed by this issue. I’m not sure if it was by design or coincidence that most of the stories fall into that “quirky” category that has become one of the badges of Japanese literature. Almost every story was a metaphor brought to life, an idiom taken literally, or a surreal twist on reality. Great, no problem with that, but not a whole magazine of nothing but. In addition, the Haruki Murakami short story, one of the few he’s ever written from the female perspective, is quite sickening. The highlight, as always for me, was a Hideo Furukawa story of walking through his native Fukushima after the meltdown. This is actually chapter one of a longer book that hopefully is also being translated. More Furukawa in English, please!

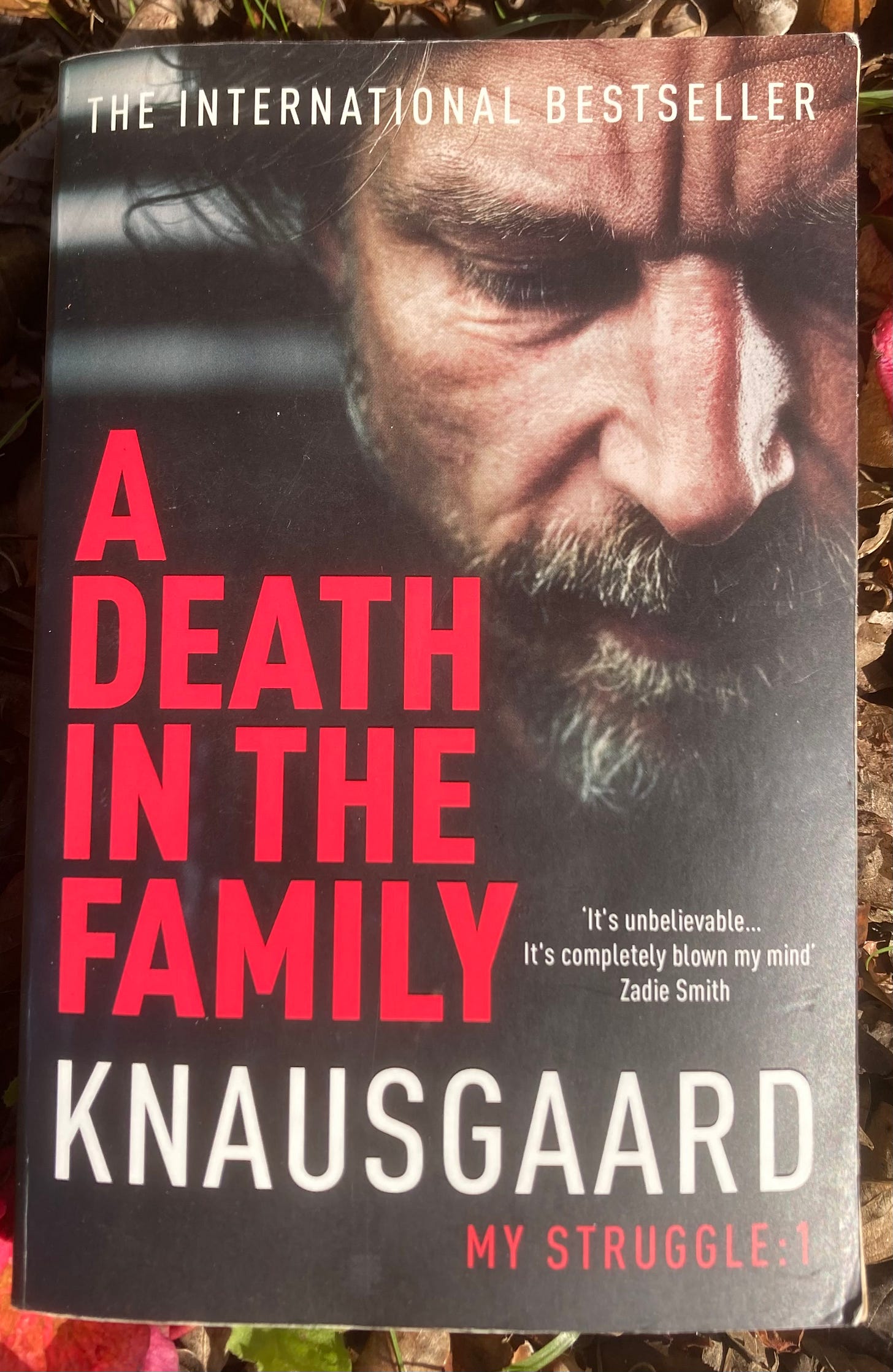

The month, and my spring vacation, ended with something I’ve been meaning to get round to for a very long time: Karl Ove Knausgaard’s A Death in the Family, the first part in his My Struggle series. I read so much about this in the media when it came out, and since in academic journals, that I felt as if I’d read it without actually sitting down to do so. I’m not sure why, but I seem to have an allergy to hyped books, even if the hype is utterly deserved: White Teeth, Shuggie Bain, A Secret History, all books I love but I put off reading for months, even years, so I could experience them removed from the media buzz. With Knausgaard, this feeling increased because he was doing something with which I’ve long been fascinated. The idea of using the novel form to tell true stories is not really done in English, although it’s pretty common in Scandinavian literature and entirely unremarkable in Japan. The line between fiction and non-fiction has always intrigued me—so much so that a chapter of my PhD focuses on that division—and my aforementioned concern with novels as a form and not as a vehicle for story instilled Knausgaard’s work with an importance before I ever opened the page. I’m happy to say that it was both over-hyped and also excellent. Over-hyped because the media’s obsession with it being a true story!!!! really isn’t all that remarkable if you accept that “novel” is not a synonym for “long fiction.” It’s an excellent, brutal, detailed story of a toxic father-and-son relationship, and that would be true whether you knew Knausgaard’s biography or not. In fact, the media—and by extension his publishers—somewhat ruined the effect of the writing by focusing on that simple fact. He didn’t even change the names!!! What madness is this? The inside back cover of this edition even has a quote from Knausgaard after the fact, reacting to the reaction. That became the selling point: What the novel was about. Not the story, not the writing. The honesty of it. I’d rather have come at this fresh, with zero expectations. I’d certainly have read it much earlier. That said, I’m glad I finally have.

Just wanted to say I always enjoy your newsletters. I share your aversion to overly-hyped books, but I'm also curious to know what some trusted reviewers have to say about new releases and about re-discovering older books. When the media heats up fast and becomes overwhelming, I have to wait (sometimes a long time) to plunge into the book(s). Thanks for your frank insights.