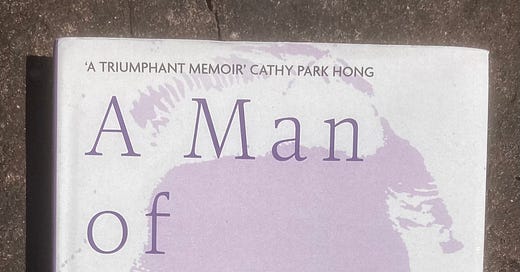

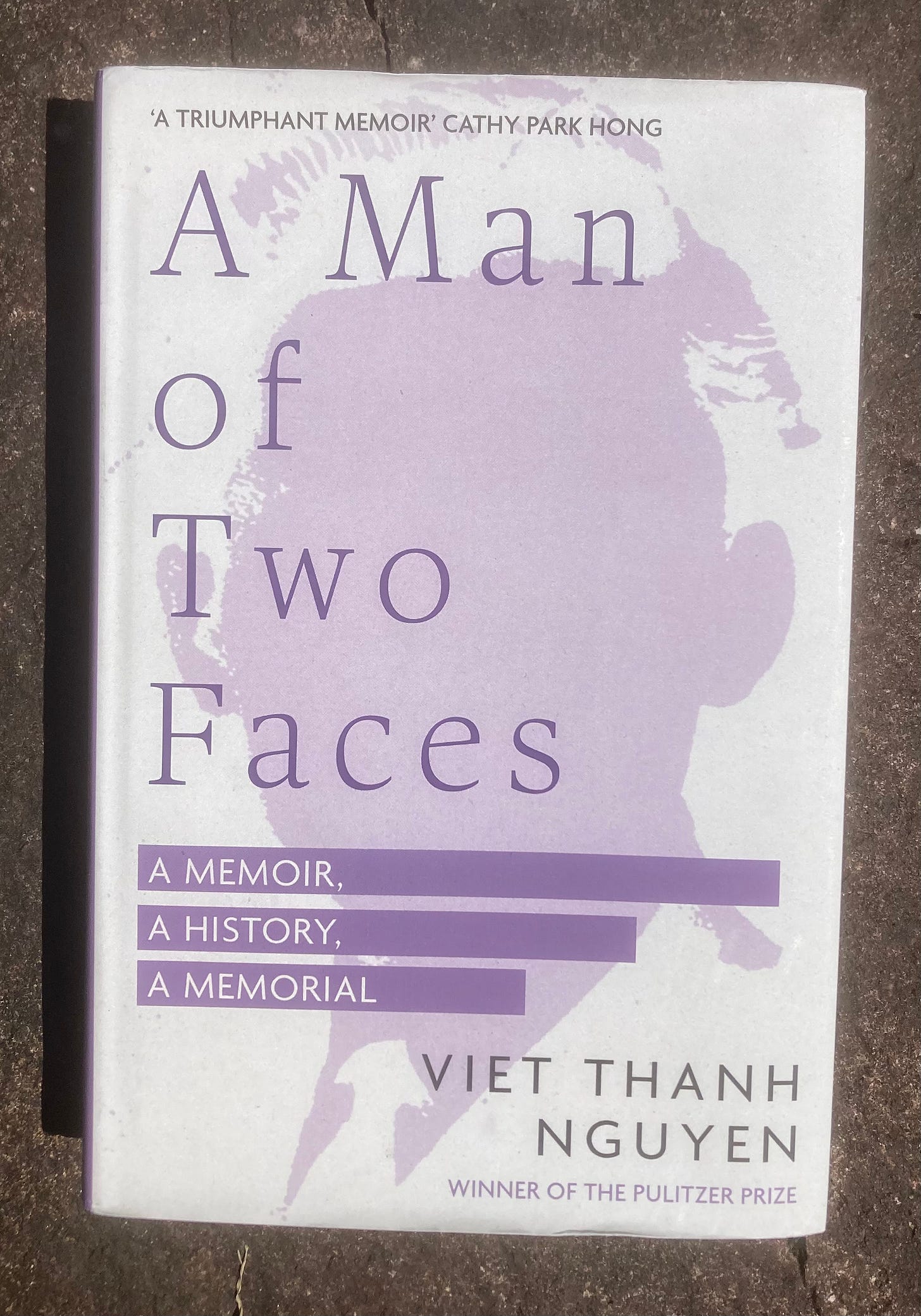

Viet Thanh Nguyen was already one of my favourite writers. His novel The Sympathizer (now an HBO series that I can’t seem to get in Japan) is a brilliant book set during the Vietnam War and after, among Vietnamese refugees in the US (it’s also a wonderful satire of US “white saviour” Vietnam war movies). He has another novel, a collection of short stories, and edited a book of essays by refugee writers called The Displaced (where I first encountered Porochista Khakpour whose new novel Tehrangelese I finally got my hands on this month), all of which I adore. His latest, A Man of Two Faces, is a memoir about growing up as a Vietnamese refugee in California, his torn identity, his relationship with his parents, and his wider experience of racism in the US. It does not pull its punches. It is brutal. It is powerful. I had to put it down multiple times, it hit so hard. It’s the clearest, most arresting takedown of unconscious bias and white privilege I’ve read so far, and as such was (rightly) hugely uncomfortable to read. His evisceration of white supremacy in pop culture was particularly difficult for me since many of the movies he writes about are ones I once loved unquestioningly. His analysis of the racism in them seems so correct and obvious now, which I guess is the point, and the whole problem with white privilege: oppression and othering looks “normal” to those not being oppressed or othered. He says that writing should “cut to the bone” and he has done that and then some, but more than anything his rage is palpable, soaked into every page of the book. This is not an easy read (what must it have been like to write?) but a hugely important book, visceral, vital, and rage-inducing. It’s also poignant and frequently hilarious. I urge everyone to read it. This one section, for me, encapsulates the heart of his writing and is, to my mind, simplest encapsulation of the world we live in today:

I’ve written extensively about David’s second and third novels, Kanazawa and The Heron Catchers, here and for the Japan Times. Both are set in Japan and right up my street. His first novel, however, is set in Vietnam and has gone out of print (hopefully not for long). Being a fan, I tracked down a secondhand copy and jumped in. It’s excellent stuff, treading some of the same paths as his other books (American men living abroad in Asia; love, language, and lashing of miscommunications). The writing is great. His descriptions of Hanoi in particular made me want to return to that city as soon as possible, which says something about how evocative it was. Reading people’s works out of order means your always going to spot developments and improvements in their skills, and that was the case here, but if this is republished, it will be well worth getting hold of.

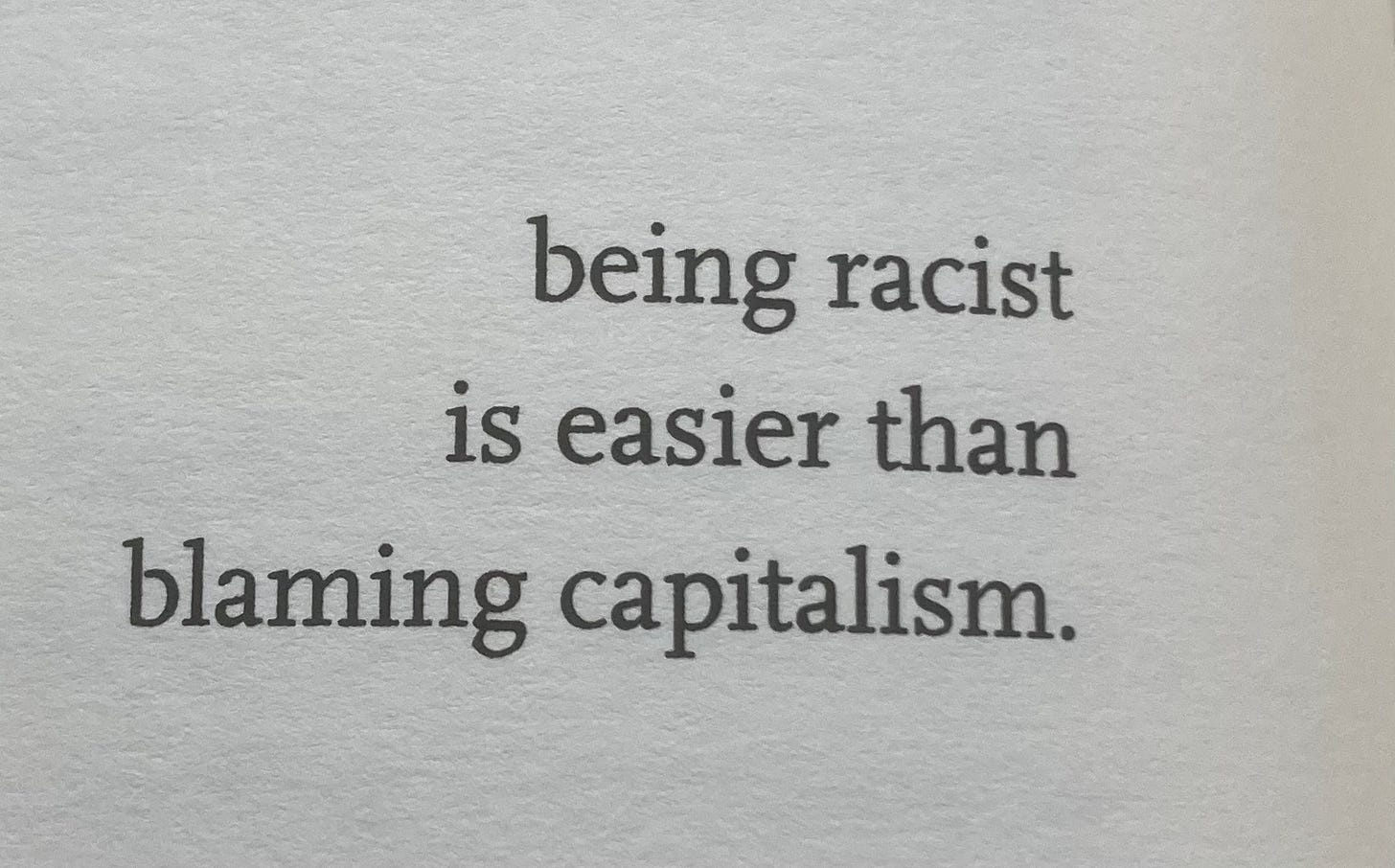

I picked this up in Cambodia in February and finally got round to it. In about 2007 there was a flurry of articles about Cambodian rock music pre Khmer Rouge, and how the brutality of the regime effectively destroyed a vibrant and interesting scene. I read a fair bit about it at the time and listened to a few things online, but never really dived in too deep. Haythrope’s book goes into more details. Reading music books when you don’t know the music is always a bit odd, but the history and the tragedy of what happened to these artists is fascinating. The stories of people literally building their own electric guitars since there were none to be had in the country are pretty inspiring too. A reminder of what rock n roll is supposed to symbolise.

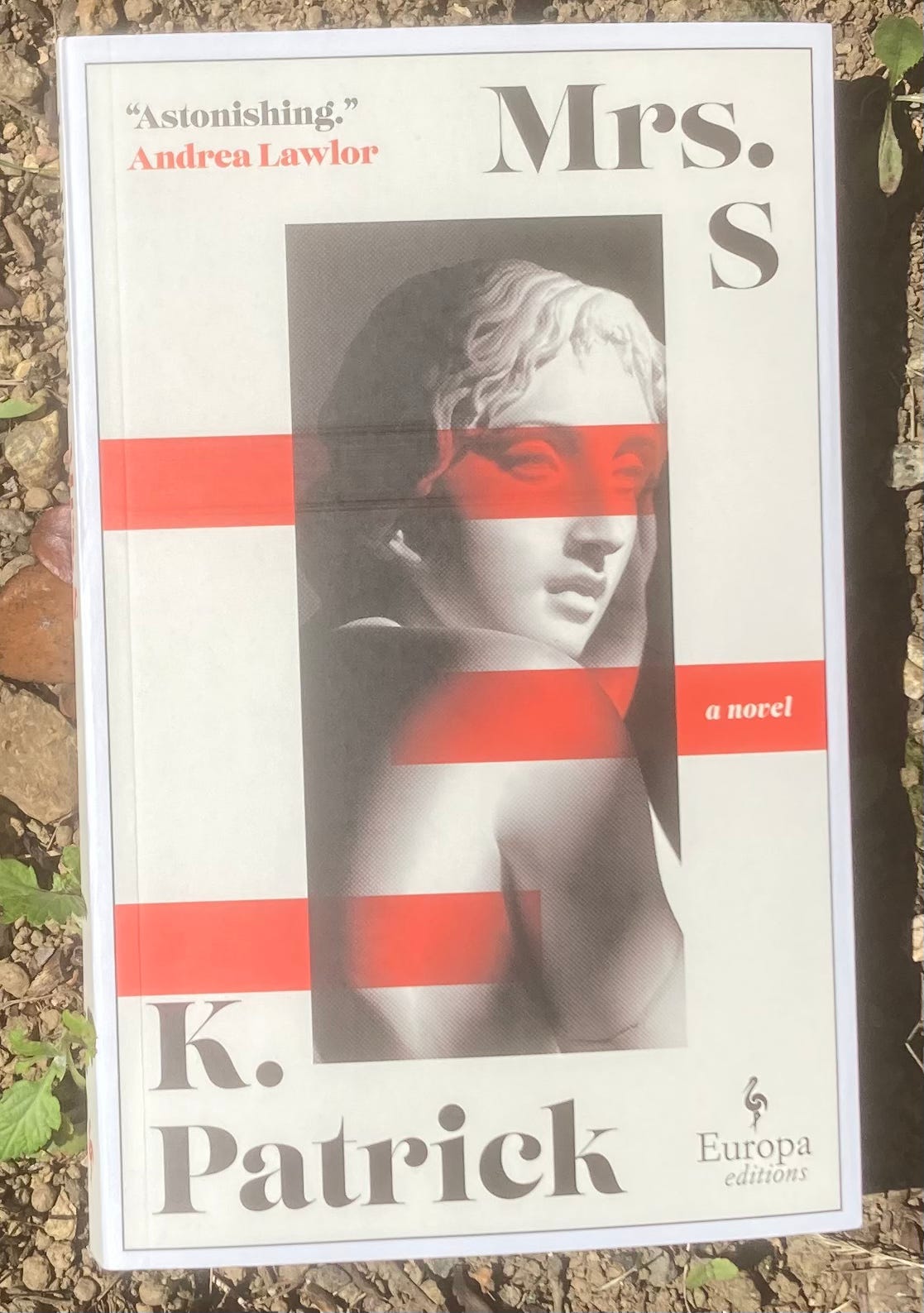

Andrea Lawlor is correct: Astonishing. It’s not exactly a hot take that K. Patrick is a brilliant writer—Granta named them one of the best young British writers in 2023—but I might as well add my voice to the clamour. Yes, astonishing. Stylism went out of fashion a couple of decades ago and I hadn’t realised how much I’d missed it. Ostensibly the story of an Australian woman working in one of those old fashioned English all-girls’ schools as the “matron” and the intense love affair that develops between her and Mrs S, the headmaster’s wife. The magic is in Patrick’s sumptuous prose. It reminds me of Ali Smith but whereas Smith’s use of language can be deliberately distancing, Patrick uses every trick in the book to bring the reader deep inside their world, enveloped in impressions, perceptions, images, and emotions. Think Woolf with a much more pronounced sense of humour. Great stuff.

Thanks for the positive review of Lotusland, Iain. (New edition coming in March 2025, btw.) Also, I'm sure you've seen the Cambodian 60s rock and roll documentary Don't Think I've Forgotten: Cambodia's Lost Rock and Roll, but in case you haven't it's well worth watching. It's viewable in its entirety on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ESD6RTTzmqY