There’s something slightly odd about beginning the new year with a sequel, but I’d been looking forward to Ian Green’s The Gauntlet and the Burning Blade (the follow up to 2021’s The Gauntlet and the Fist Beneath) and once the brain fog of Covid lifted and I could read more than two pages at a time, I settled down with this. The Rotstorm trilogy is a fantasy series in the classic tradition, with sword-swinging warriors, gods, goblins, magic, mayhem and mythology. The gap between reading books 1 and 2 meant it took me a while to pick up all the threads but Green does a good job of recapping book 1 without descending into “previously on…” territory. Being the middle book in a trilogy (as I understand it), it is inevitably darker and is filled with hints of twists and turns to come while not coming to any real conclusion. Without giving away spoilers or spending paragraphs explaining the story, I suspect that Green is doing something very interesting with plot and perspective here and I can’t wait to see how it develops in the next installment. The cherry on top the the tree is that Green is a fellow Aberdonian and slips sly references to his home that make me chuckle. Great stuff.

By pure coincidence the next book I pulled from the shelf was by another Aberdonian writer, albeit one by adoption. Leila Aboulela was born in Egypt and raised in Sudan, but a long time ago made Aberdeen her home. I’ve read a handful of her books but thankfully haven’t yet exhausted the supply. Lyrics Alley is a beautiful novel in the traditional sense (character driven rather than plot driven; gorgeous stylistic prose rather than route one storytelling) set in 1950s Sudan at the end of British rule. It’s one of those novels that is an experience rather than a story and so anything I can say to recommend it would fall far short of replicating the effect reading it had on me. I read most of it on a rainy Sunday afternoon in front of the fire with a glass of whisky, and I thoroughly urge you all to repeat the experiment in the hope you will achieve the same results.

The Thorn Puller by Hiromi Ito, translated by Jeffrey Angles, was an advanced copy from Stone Bridge Press. I’m going to be writing about it for Metropolis so I want to keep my powder dry, but this is rightly worth the hype. On one level it’s the story of a middle-aged Japanese woman dealing with her aging parents in Japan and her life with her American husband and her daughters in California. On another level it’s a complex fabric of Japanese literary and mythological allusions, most of which were beyond my grasp but which hinted at a rich, textured novel that will reward re-reading. Hiromi Ito is a big name in Japan but this is, as far as I know, her first book to be translated into English. The first of many, I hope.

The Long Side of the Midnight Sun is a long narrative poem by Warren Decker, published by Isobar. I know Warren from various conferences and online events (as well as a few post conference festivities) so I was curious to get hold of this book. Curious is probably the most apt word. It’s probably easiest to just quote the blurb:

“Transcribed from the handwritten contents of a mysterious fleece-bound notebook, The Long Side of the Midnight Sun by Warren Decker is a poetic drama in eighteen acts which tells the story of our hero, Craig, who travels with his wife and son from Osaka to Maryland for a Christmas reunion with his extended family.”

It’s funny, surreal, graphic, surprising, and a real example of how narrative long-form poetry can work. Some of the rhyming couplets that switch between Japanese and English are particular highlights. I can’t wait until the next conference to pick Warren’s brain about this brilliant, bizarre book.

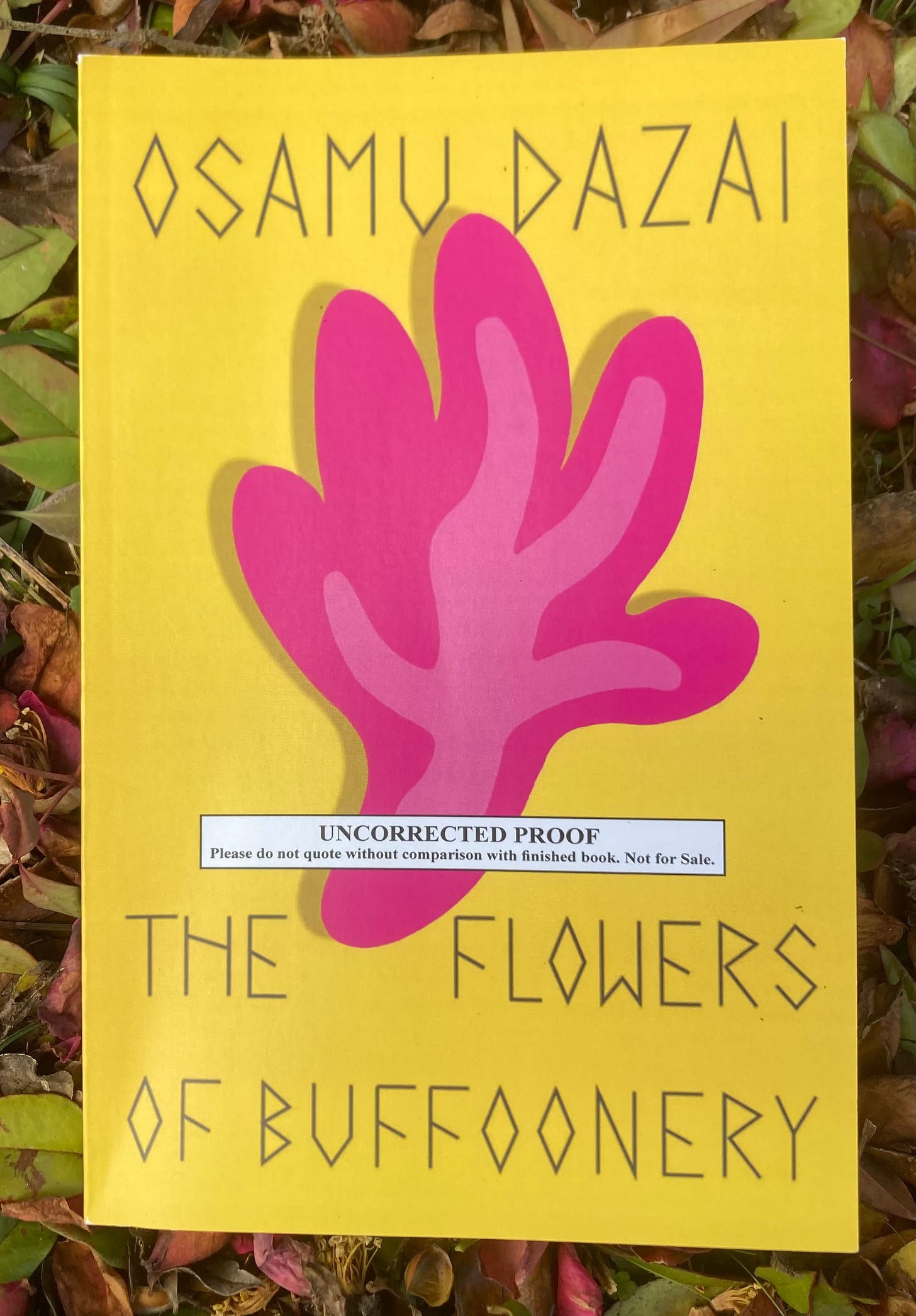

Another advance copy, this time from New Directions, is Osamu Dazai’s Flowers of Buffoonery. A prequel to perhaps his most popular novel, No Longer Human, this couldn’t be more different in tone from that book. Ostensibly it tells the story of Yozo, a young artist who survives a suicide pact with his lover, and his recovery in a sanitorium in Enoshima with his two friends and a nurse. His friends take little seriously and see their job as keeping Yozo’s spirits up, leading to much of the buffoonery of the title. This short novella however is also a fantastic example of postmodern fourth-wall breaking, as the narrator constantly interrupts his own narrative to apologise for the quality of the writing, to explain how the plot and the characters keep ruining his intentions by heading in directions of their own, and generally undermining what should, on paper, be a serious, powerful story. The more I read Dazai, the more I love his writing and his mind, so I’m glad there has been a recent rise in the number of his works being translated. So much so, that there’s a serious risk of him overtaking Kenzaburo Oe as my favourite Japanese novelist.