Max scratched his belly, far from contained by his Slayer shirt, and lit another cigarette. He’d have to get dressed sometime and head out, but felt no sense of urgency. His appointment with Frankie was at four. If he left early he could do a round of the charity shops on the way. Maybe, just maybe, someone would’ve donated Maiden’s Sanctuary seven-inch or Sepultura’s Slave New World on ten-inch orange vinyl. You never knew what treasures might turn up.

The turntable clicked out. Slipping Megadeth carefully into its sleeve, he returned it to the ‘M’ part of the 80s Thrash / Speed Metal section of his library. He’d been meaning to listen to Nine Inch Nails since hearing that opening sample while watching THX-1138 so took it from the 90s Industrial ‘N’ section and placed the needle. The dull thwacking sound of truncheon on flesh came out the nine perfectly positioned speakers. Happy, he lit another cigarette.

The flat could do with a clean. He pulled the curtains back unleashing a cloud of dust into the room, coughed, spat into a half-finished coffee. With the exception of the records, everything in the flat was in a state. He picked up some socks and an ashtray, the force draining from him, his body sagging like the puppet-master had gone for a piss. He dropped the socks again. Maybe tomorrow.

It was too early to start drinking, not if he wanted to last the night. For sure he’d have a little something with Frankie, and from there it was on to the Cauldron for a look at Mickey’s new band. Then there was that invite to meet Kenny late on.

He still hadn’t decided if he was going or not. The email: getting in on the last flight. Late beer? Catch up, talk about the future. What did that mean? Did he just want to rub his success in Max’s face?

Max and Kenny had gone to school together, bonded over copies of Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Raw. At first they tried starting a band but both were hopeless musicians. Then there were a couple of fanzines. After that the obvious next step was to start a label, Biotech, releasing cassettes of mates’ bands, but it quickly crashed and burned. The world hadn’t been ready for them and, if he were honest, the bands weren’t up to scratch. Kenny went to college, studied marketing or something. Max tried his hand at a few things, never quite finding his niche. They drifted apart, not quite lost contact but Kenny was down in London, gaps between visits getting longer and longer. Then one day Max saw Kenny’s name in Kerrang! He’d started a label on his own, Randan Records, signed one of those awful rap metal bands, got a single in the charts, an appearance on TV. The another. And another. Nu-Metal’s Alan McGee they were calling him.

That was years ago. Max had followed Kenny’s career through the music press. Success after success. Max was freelancing, getting articles in the metal magazines he’d read as a kid. They bumped into each other a couple of times at festivals, Kenny and his entourage, fist bumps, hugs, promises to catch up. Promises to stay in touch. They never had. Then the email came. Wanted to talk about the future? Why?

Oxfam annoyed him. As usual they had some decent stuff, but all ridiculously priced. It was a charity shop for christsakes, everything should be 10p, 20p, not twenty, thirty quid. Problem was, the Oxfam staff knew what they were about. Very difficult to slip a rarity passed them. He’d had a few successes in the past, but usually all Oxfam was worth visiting for were CD singles to keep the completist in him happy.

He left with a couple of those and headed for the Cats Protection League where, if you were lucky, you could get a coloured twelve inch for a couple of pence. Winter was starting to bite, a bitter icy wind burling newspapers along the street and giving even the seagulls a hard time. He glanced at his watch. He was already late.

“Crow, you owe me a fiver.”

“How?”

She looked up from the laptop at Max’s coated bulk coming down the stairs into the basement shop.

“Not yet,” said Crow. “Just because he turned up, doesn’t mean he’ll go through with it. You know Max. Never sees anything through. Bottles more than Glenfiddich.”

The deep red walls of Crow and Frankie’s tattoo shop were adorned with photos of their work. Tribal swirls, dragons, hideous Japanese geisha-like ghosts, naked women. In between the framed photos hung Frankie’s collection of hubcaps. No one knew why he collected them, least of all Frankie. He’d woken one afternoon with a complete set from an E-type Jaguar and no memory of acquiring them. From there the collection seemed to grow of its own accord.

“Crow,” Max said.

“Max,” Crow replied, looking back down at her phone, taking a sip of her Jack and ice.

Crow got her name, rather unimaginatively, from the fact that she was never to be seen in anything other than black. From her dyed jet hair to the steel tips of her biker boots, the only thing not black was her skin, powdered into the palest of whites, and the silver piercings decorating various and seemingly random parts of her body. Even her lenses were black.

“Hey, Max,” said Frankie. “Wasn’t sure if you’d make it.”

“No worries there. This time I mean it. I’m going to get it done.”

“Great, take a seat and I’ll get the sketches.”

Carcass album played in the background. Max took the Dr. Pepper he’d bought at the newsagent from his pocket and cracked it open.

“How’s business?” he asked Crow.

She looked at him slowly, with unconcealed contempt. After a few seconds she clearly decided she might as well answer him.

“Alright.”

“Good, good.”

“How’s the label,” she said, not even trying to hide her sneer.

“Early days.”

“You manage to sell any of those CDRs?”

“Some.”

Max was trying to relaunch Biotech Records. His first hopefuls had been a death metal band from Irvine. He’d put up the cash for a day in the studio. The results had been less than ideal. They’d sold about a dozen on Bandcamp, a few CDs at gigs, but that was about it.

Frankie returned and sat across from him, laying his sketch book on the low table. He used a piece of ripped black material to tie his dreadlocks back and opened the book.

“This is what I’ve come up with,” he said. “You said you wanted Iron Maiden’s Eddie wearing a Scotland top and holding a Flying-V guitar.” They turned through a couple of pages showing exactly that. “I also did a few with a bit of surrounding. Standing on some skulls, standing on the Terminator’s head, standing on the Predator’s head. Basically, lots of him standing on heads. Then we can do different things with his face, flames from the eyes, snakes, that kind of thing.”

Max flicked back and forth through the book like an art collector calculating an investment. “I like the Terminator one,” he said at last. “Rather than fire coming out of Eddie’s eyes can you just make the pupils flames?”

“Like this?” Frankie rubbed out the eyes of close-up study of Eddie’s face and replaced them with candle-like flames.

“Yeah, a wee bit fiercer, but yeah.”

“Okay. Next. When are we going to start this?”

“How long will it take?”

“A wee while. A few sessions, especially once we start putting the colour in. You want it on your back, yeah?”

“Yeah.”

“Well I can do the outline in a couple of hours. Say, tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow?”

Crow looked up. She’d been waiting for this moment; when it came to the crunch she figured he’d back out, run scared. It always happened this way. No balls.

“How about the next day? I’ve got a late one tonight.”

Crow twitched slightly in surprise. “You’ve got to finish Matt’s piece the day after,” she told Frankie.

“Nah, he texted me, cancelled. They moved his case forward. I’m free.”

“More than you can say for Matt,” said Crow.

“The day after it is then, Max,” said Frankie.

“Aye. The day after. Aye.”

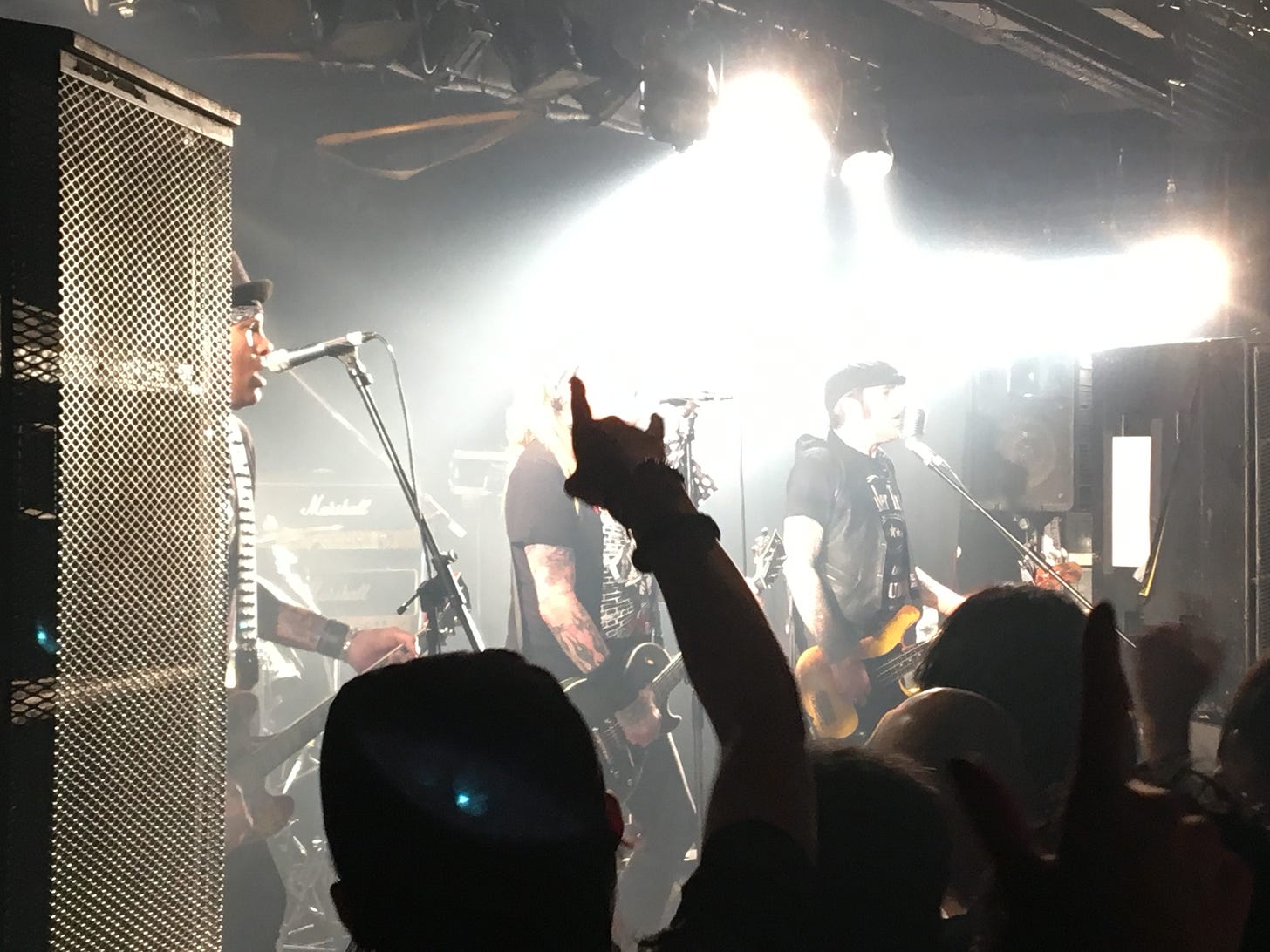

The rain had started and The Cauldron was steaming, not a person inside having escaped the wet, mainly through standing in the street smoking. Max nodded to a couple of people he knew but went straight for the bar. They had Red Cuillin on tap this week and he wasn’t going to miss any of that.

“Pint please, Paul.”

“Buying again is it?”

“Aye, couple of singles, nothing special.”

“You must have the lot already.”

“No fear. They make it faster than I can consume it. Quiet day?”

“Aye. It’s the wind, keeps the auld boys inside. They cannae manage vertical on days like today.”

Max sipped his pint, looked around. The place was dead. Only seven people, not counting the bands, the staff and himself. Cath from the Sanctuary blog was in a booth swearing at her phone. Max needed to speak to her. He’d been trying to write for Sanctuary for months but she kept sending his articles back. He figured it was personal.

“Hey, Max,” said Paul. “Isn’t that Kenny Banks a pal of yours?”

“Aye, same school.”

“Apparently saying he’s selling that record company. Making millions off it.”

“Is that right?”

“Aye. Imagine that. Selling a business for money like that.” He looked around the bar, far from satisfied with what he saw. “Wonder what he’ll do with it?”

“Knowing Kenny most of it’ll go up his nose.”

Kenny was selling Randan records, was he? Well presumably the email had something to do with that. The timing. So he did want to rub Max’s nose in it. Come for a beer to celebrate my move from millionaire to billionaire. I’ll pay for everything. See how far I’ve come. How far from you I’ve travelled.

A fantasy played in Max’s mind. He met him in some fancy bar. Kenny greeted him like a returning hero, big hugs for all to see. They had a chat. Kenny acknowledged that he’d sold out. That Randan had been cynical marketing, a money maker and nothing to do with true music. What he wanted, the reason he’d sold Randan, was to go back to square one. Pick up Biotech and run with it, now he had the industry savvy and the money. Max had his ear to the musical underground. What a team they’d make. World beaters. No more squalid flats. No more public transport. Limos and mansions and metal gods on speed dial. Talk about the future. It had to mean Biotech. It all fit together.

He finished his pint, got another and wandered over to sit with Cath. Cath was a threat of a woman, long thin hair, denim jacket that permanently smelt of damp. Her notebook was much the same: Whatever scraps of paper she had lying around hole punched and tied together with old shoelaces. She always wrote with a stubby pencil sharpened with a knife. How did she keep knocking his stuff back when proper magazines would run it?

“And how’s you Cath?”

“Usual. IBS playing up, boss is a twat, world’s falling apart.”

“You had a chance to look at that piece I wrote on Enslaved?”

“Aye. What can I say, Max? If you’re no gonnae take my advice about your writing, I’m no gonnae publish it. If you cannae stick to a word count, at the very least proofread and spell-check it, would you? At the moment it’s just rambling nonsense.”

“There’s more than one way to write, Cath.”

“There’s two ways: good and bad. Max, you’ve been giving me the same stuff for years. You’re the only person I know that doesnae get any better with practice.”

He looked at the flyer for tonight’s gig, a cheap photocopy advertising Mickey’s band Upye and Everlone. He’d never heard of Everlone but he sure as hell wasn’t going to ask Cath about them. It wouldn’t do for the CEO of Biotech to look like a moron. No one else had joined the crowd and Upye debuted to a largely indifferent room. It was probably for the best. They weren’t the kind of thing the newly enriched Biotech would waste time on. Biotech was big league now.

He met Kenny in Therapy, a trendy wine bar Max had never been in before. Chrome furniture and no straight lines, Ikea artwork on the walls, some EDM nonsense looping through the speakers. A quick glance around. He was a few minutes late but still there first. Even before his success Kenny had a fractured relationship with time. Max walked up to the bar, looking for a stool.

“If you’d like to take a seat, sir, I’ll bring a menu over.”

“It’s alright, I prefer to stand at the bar.”

“I’m afraid there’s no standing at the bar, sir.”

“No standing at the bar? But it’s a bar. Bars are for standing against.”

“Not here, sir. If you’d come this way …”

People were looking. He followed her, trying to squeeze through the narrow gaps between chairs that she sashayed through. Impossible. His bulk shifted a couple of empty seats, the scrape resounding clear in the air. He hated Kenny for making him come here. For being late. For everything. Sitting with his back to the door he glanced through the list of piss European beer. No ales. He chose a Guinness, got her to leave, tried to blend in.

To look busy he took out his notebook, sketched ideas for business cards. Nothing cheesy, no crossed guitars or anything like that. Simple. Max Halford, CEO Biotech Records. Not black on white. Something a bit unusual, maybe a deep, deep purple. Shifted under the lights. The background, embossed, raised but the same colour as the rest of the card, the body of a Flying V guitar. You could feel it but couldn’t see it. Classy.

“Nice.”

Kenny was standing over his shoulder. Max rose, they shook hands, sat. He looked as expected: Tailored suit, no tie, Converse rather than shoes, hair exactly tousled. The kind of dishevelled perfection only money can buy.

“Thanks for coming,” said Kenny. “I didn’t think you would, your reply came just as I was boarding.”

“Commercial or you got your own jet now?”

“Ha, I’m unemployed now, didn’t you hear?”

“I can’t imagine you’ll be signing on.”

“No, though they probably owe me the amount they’ve taken in taxes. Always direct, Max. That’s what I like about you. Yes, I got a good price. Can I have a Cantillon, please,” he said to the waitress. “So how are you, Max? Haven’t seen you since Download. What have you been up to?”

“Oh, you know. The usual. Bit of journalism, writing for a couple of publications. Supporting the local scene. There’s this cracking band from Irvine called Physical Sanctions.”

Kenny shook his head to show he hadn’t heard of them.

“Next big thing?”

“Could be.”

“Anyone else worth hearing about?”

“Not really. The scene’s a mess. Fractured. No descent venues anymore. That’s something you could do with all your… free time, get a proper dedicated rock venue going.”

“Not a bad idea, actually. Covid tanked a lot of venues so there must be buildings going spare. But no, I’m not looking to rush back into anything.”

“Bit of time off?”

“Looking around for the right idea.”

They had a couple more beers then moved on to an Indian / Mexican fusion restaurant when Max said he fancied a curry. Two old friends who weren’t really friends anymore, they circled each other, not opening up too much, not giving too much away. Meaningless chit-chat. Kenny was highly experienced at appearing to talk and listen without actually being invested in the conversation. Max was lost. All he could think about was how to get back onto the topic of Biotech without appearing desperate. Kenny clearly was in no rush to come to the point. They finished their madras enchiladas and Kenny suggested going to the Malt Whisky Society for a dram.

Enfolded in armchairs, crystal tumblers resting on satisfied stomachs, Max could take no more.

“So. The future.”

“The future,” said Kenny, raising his glass.

“No. I mean, your email. You said you wanted to talk about the future.”

“Ah, yes.” He gazed at the dark amber in his glass, sniffed it. “Running Randan was great fun, and I don’t regret any of it, but I miss the early days.”

Here we go, thought Max. Sell out. Back to square one.

“Finding a band, promoting them, in-store gigs, first festivals. Doing that stuff with mates. Those were great days. But it’s all different now. The technology, the money. That model is gone. Labels are dead.”

“Labels are dead?” He all but spilled his whisky.

“Dead. That’s why I sold Randan. If you know your house is going to fall down, it makes sense to get shot of it ASAP. In a year or two Randan will be as dead as… what was that label we pissed around with when we were kids? Biotech? Randan will be as dead as Biotech.”

Nausea. None of this was supposed to happen. This wasn’t how he’d imagined it. This wasn’t what he’d planned. “How … how can labels be dead? People are always going to want music. Vinyl is back, record shops opening up all over the place.”

“Aye because folk our age have disposable income and will do anything to avoid going to therapy. Music’s always been about the kids and the kids aren’t buying, not in big enough numbers. For people like us labels were part of the music. Rough Trade, Creation, SubPop, Roadrunner, East West. How many great bands did we find because of label samplers? Label showcases? But kids don’t think about things that way. On Spotify the Randan logo is all but invisible. There’s no identity. That’s why it’s dead. Did you ever read about the Reformation? The whole thing the Protestant Reformers had was that there shouldn’t be anyone standing between them and God. No priests, no bishops, cardinals, Popes, nothing. Me and my God, face to face. Direct line. That’s how kids think about music now. Bands. A reformation. Why do I have to talk to a publicist, send my fan mail via a third party, when my idol is on Instagram or whatever. There’s no place for us in that picture. We are Cardinals demanding that all traffic goes through us. Traffic cops. No one’s listening. We’re out of a job.”

Max couldn’t take it all in. He’d been wrong-footed, pushed off balance.

“So we’re irrelevant? What are you going to do? Start a streaming platform?”

“Essentially, yes.”

“What?”

“The problem now is that it’s hard to get noticed. As you said, the scene is fractured. Kids upload their music to Spotify and it sits there will a billion other singles fighting for any kind of oxygen. Unless it’s picked up by some random algorithm, that’s it. What I’m thinking about is more localised. Spotify but for specific locations. We used to go to the Cauldron for rock night. We’d see three or four bands and listen to whatever the DJ was playing. That’s how we’d find music. It was all in the same location with the other crap filtered out. This app will do that for the digital age. Kids in this city will find all the rock bands curated, available in one place so they can check them out. Your idea of then having a dedicated venue isn’t a bad one – listen online then come see them live. And not just rock, every genre.”

“And you’re going to do this.”

“I’m going to invest in it. It’s not that hard, it’s the same tech just a new spin.”

“What about me?”

“What do you mean?”

“You said you wanted to talk about the future. Where do I fit into this?”

“Are you wanting a job, is that it?”

“No, I’m not wanting a job. You invited me out to talk about the future, I thought that meant…”

“I invited you out to dinner because I haven’t seen you in years. I haven’t seen anyone in years. I’ve been run off my feet for a decade at least. Now I’m free of it I want to catch up with all my old friends, starting with you.”

“Right.”

“Yeah, right. Why, did you only come thinking you might get something out of this? That now I was a rich guy I’d come through with a handout?”

“No one asked for a handout.”

“What are you asking for?”

“I thought … I thought you wanted to restart Biotech.”

“Restart Biotech? Why the fuck would I want to do that? I’ve done that. I started a label. It was a success. Why would I want to do it again?”

“But Biotech was our dream.”

“No, our dream was to work in music. Biotech failed. I learned from that. Moved on. Did it better.”

“Aye, by yourself. We did Biotech together but you did Randan by yourself.”

“Is that what this is about? You could have come to London with me, Max. I invited you, remember? You wanted to stay here. You didn’t want to leave this town. We had our chance, Max. I took it; you stayed. You’re still the same old Max, waiting for it to be handed to you. Too lazy or scared or whatever to take that first step.”

Max woke the next afternoon raging. He’d been right. The whole thing had been one long exercise in rubbing his nose in it. Too lazy? Too scared? It wasn’t Max’s fault he’d never achieved all his dreams. Some people were just lucky. Kenny was just lucky. Well, Max could be lucky too. Luck can change.

He didn’t need Kenny’s money. It was Biotech’s time. All he needed was to find that one perfect band and he’d be on his way.

Kenny was right about one thing: Technology. That was the tool. The secret. He’d scour the internet for the right band. The perfect band. There were a lot out there. He’d need every minute. First he’d have to cancel that appointment with Frankie. He couldn’t spare the time. He had a future to build. He could already picture it. He fired up the laptop, lit a cigarette.