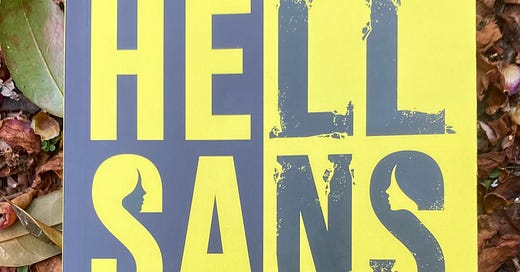

I’m a big fan of Dundas’s first novel Goblin, and when I heard she was writing dystopian science fiction, one of my favourite genres, I was pretty damn excited. HellSans more than lived up to my expectations. Set in a society where the titular font can cause a drug-like bliss in some people and extreme allergic reactions in others, it follows a familiar path of revolution via a series of unfamiliar routes and a plethora of twists and turns. The storytelling is spot on, the prose exquisite, the ideas captivating. I’d go into more detail but I don’t want to spoil a thing, you really need to read it for yourself.

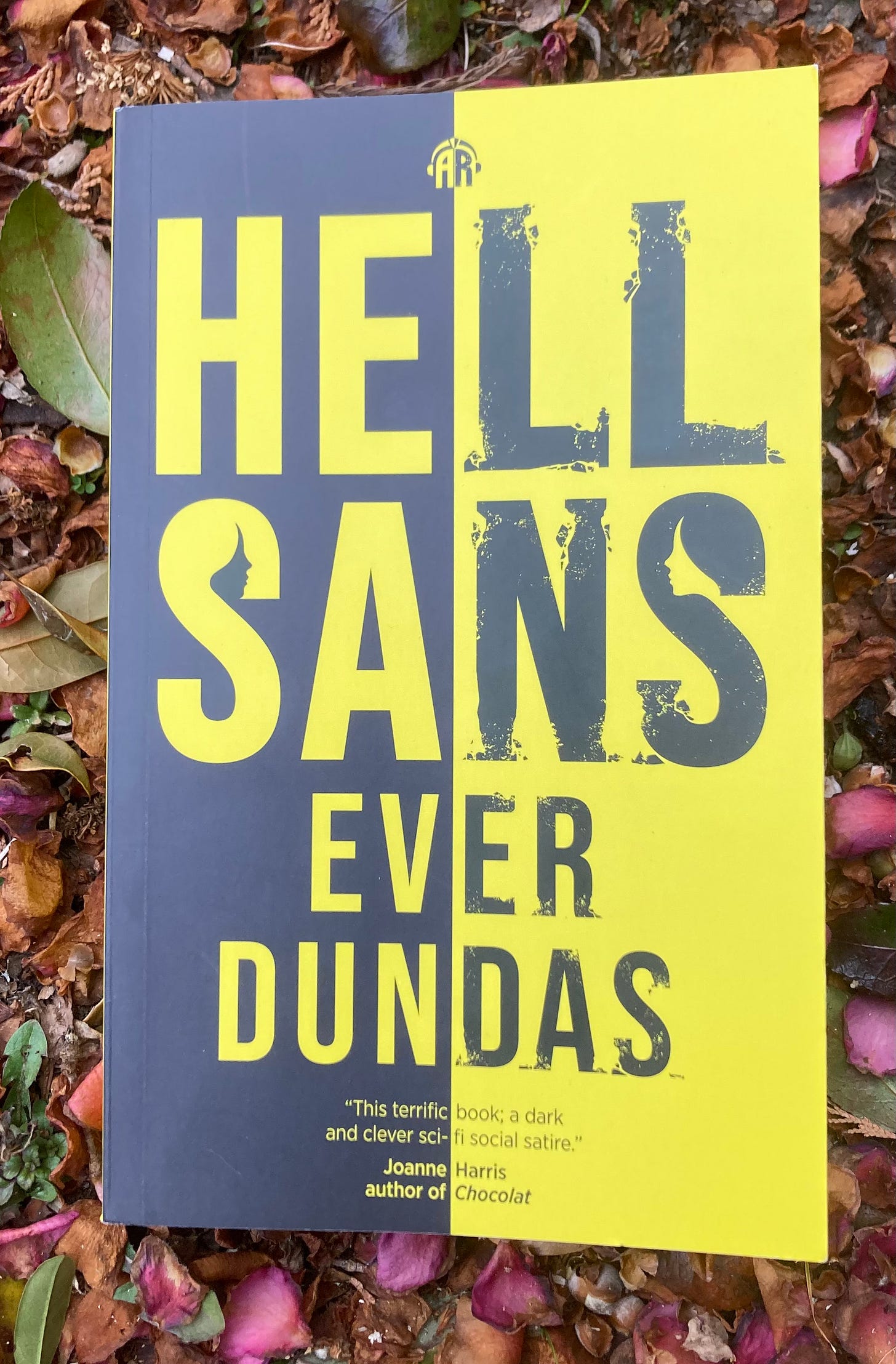

Cormac McCarthy is one of those writers of whom I keep meaning to read more. I read The Road ages ago, loved it (see above regarding genre) and then for some reason never got round to reading any more. So when The Passenger, his latest (alongside sister book Stella Maris) came out last year, I jumped in. It is brilliant and confusing in equal measure. It’s very—deliberately—Kafka-esque with main character Western being harassed by “Feds” for reasons that are never quite explained. The main fascination for me is that the book is almost entirely dialogue, with brief bursts of narration sprinkled throughout. This is something I’ve long wondered about and am in the middle of attempting myself, so it was good to see an example in the wild (precedent for when a publisher says it can’t be done: Cormac McCarthy did it). I’ve also bought his Border Trilogy so more on McCarthy to come.

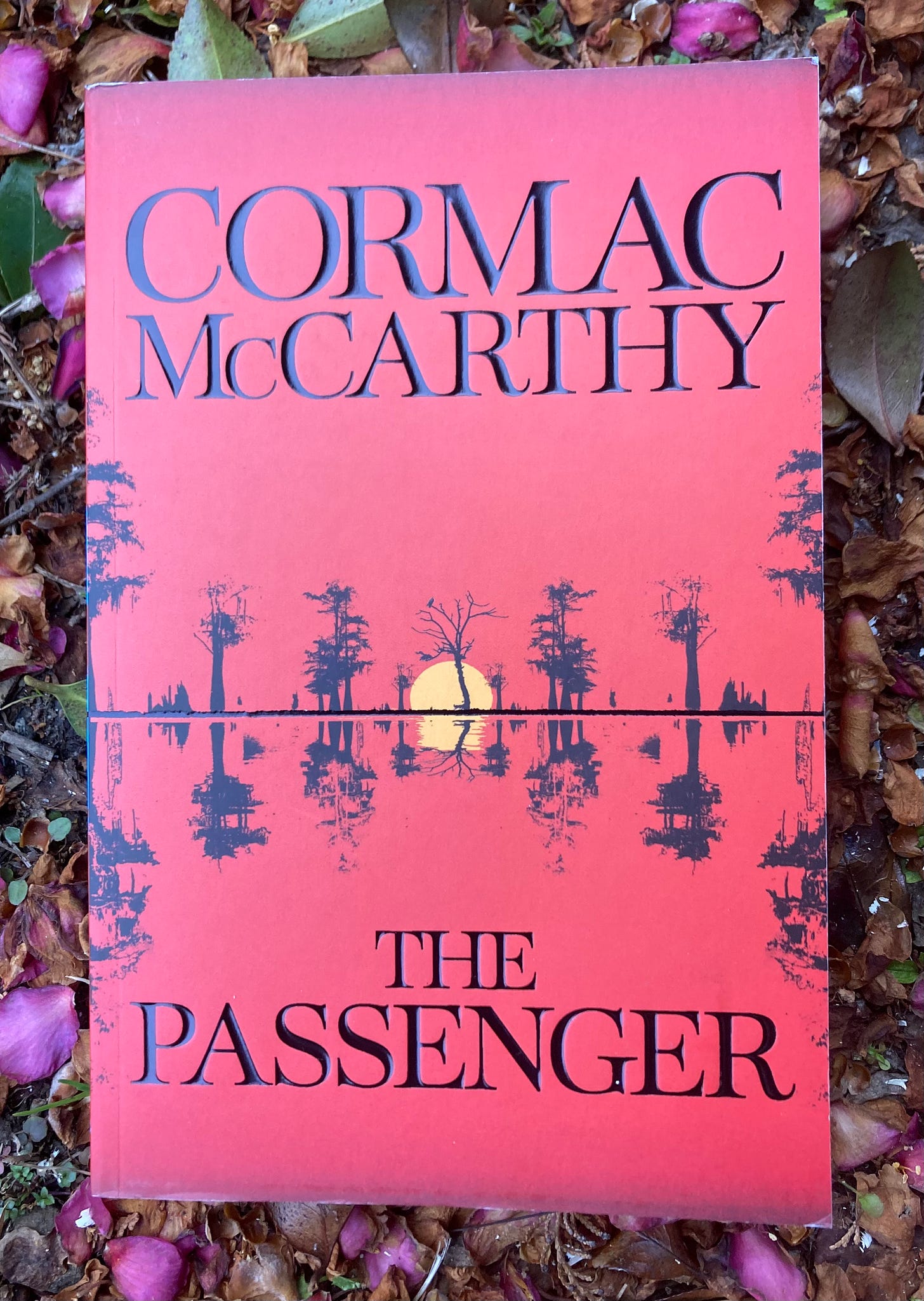

I can’t remember how this came across my radar, because fishing is really really not my thing, but Ted Hughes’s poetry is, and a quote from Robert MacFarlane tipped curiosity into purchase. Wormald is himself a poet and the descriptive writing in here is beautiful, and as a study of how biography impacts poetic output, it is both detailed and empathetic. My next book (The Japan Lights, out in August) is a mixture of travel and biography, the same as this, so I’ve been avoiding these kinds of books. Sure enough, I was very quickly comparing mine with Wormald’s, but quickly realised that’s a fool’s errand: his subject is a poet, mine an engineer, so different approaches were always going to be necessary. You don’t have to be a fan of fishing to enjoy this, or a fan of Hughes, though being a fan of at least one would help. Gorgeous prose is sometimes enough.

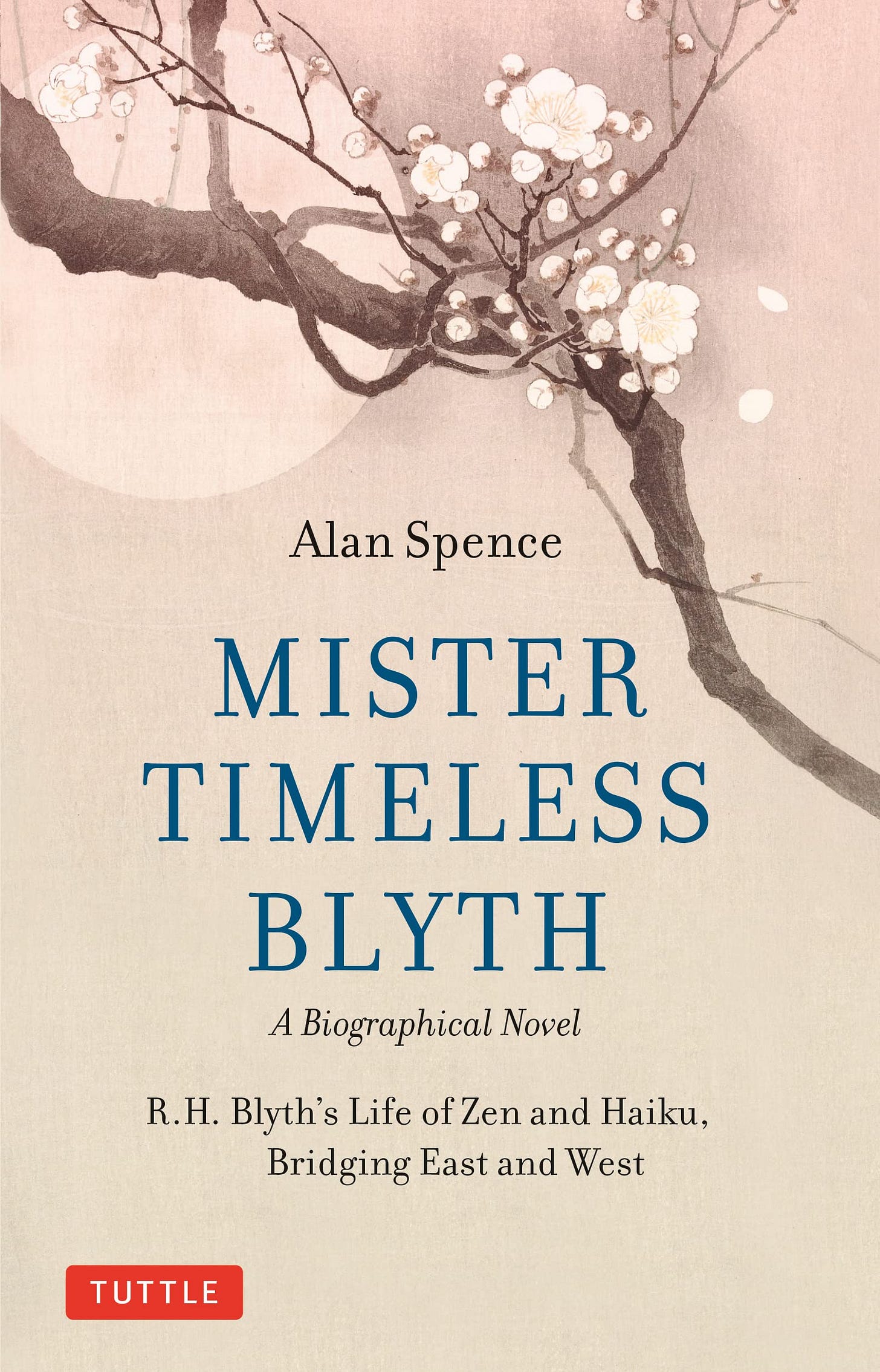

One I’ve been looking forward to for literally years. I’ve known Alan from when he was Professor of Creative Writing when I was an undergraduate at Aberdeen. Since then we’ve bonded over our shared love of Japan, and it was in 2015 or 2016 that he told me he was working on a novel about R. H. Blyth, the Englishman who, amongst other things, introduced Japanese haiku to the ‘West’. Well, it sees the light of day this March and I got an advance copy from Tuttle (much thanks). I’ll be writing about this in the Japan Times, so I won’t go into much detail here, but as always with Alan the prose is sparse and powerful, the characterisation honest and empathetic, and the subject matter fascinating. If you don’t know Alan’s work, I can’t recommend it enough. If you do, you’ll be as excited by this as I am.

Finally, Verso very kindly sent me an advance copy of Hit Parade of Tears by Izumi Suzuki (translated by Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph and Helen O’Horan). I reviewed her first collection in English, Terminal Boredom for the Japan Times but unfortunately someone beat me to the punch this time. Nevermind, it’s a rare pleasure to read a new translation of Japanese literature without one eye on a review or an interview. Suzuki’s biography is itself the stuff of great drama, and her short stories are a bizarre blend of working-class literature, science fiction, punk vignettes and avant garde experimentation. The first story, “My Guy”, had me hooked. In some ways it’s a stronger collection that Terminal Boredom, in other ways it’s a bit more manageable for people who like their fiction to have some kind of solid realistic foundation. Either way, while it’s still early in the year, this will definitely be a contender for my Japanese translation of the year. Verso calls it “wryly anarchic” and I can’t think of a better description than that. Side note for other J-Lit geeks, there are a few stories in here where you can really see that Suzuki must have been a big influence on Hitomi Kanehara (when did she stop being translated? Damn fashions).

I don’t want to miss your review in the Japan times. I ordered the book but no sign of it yet.