Call me a Dog

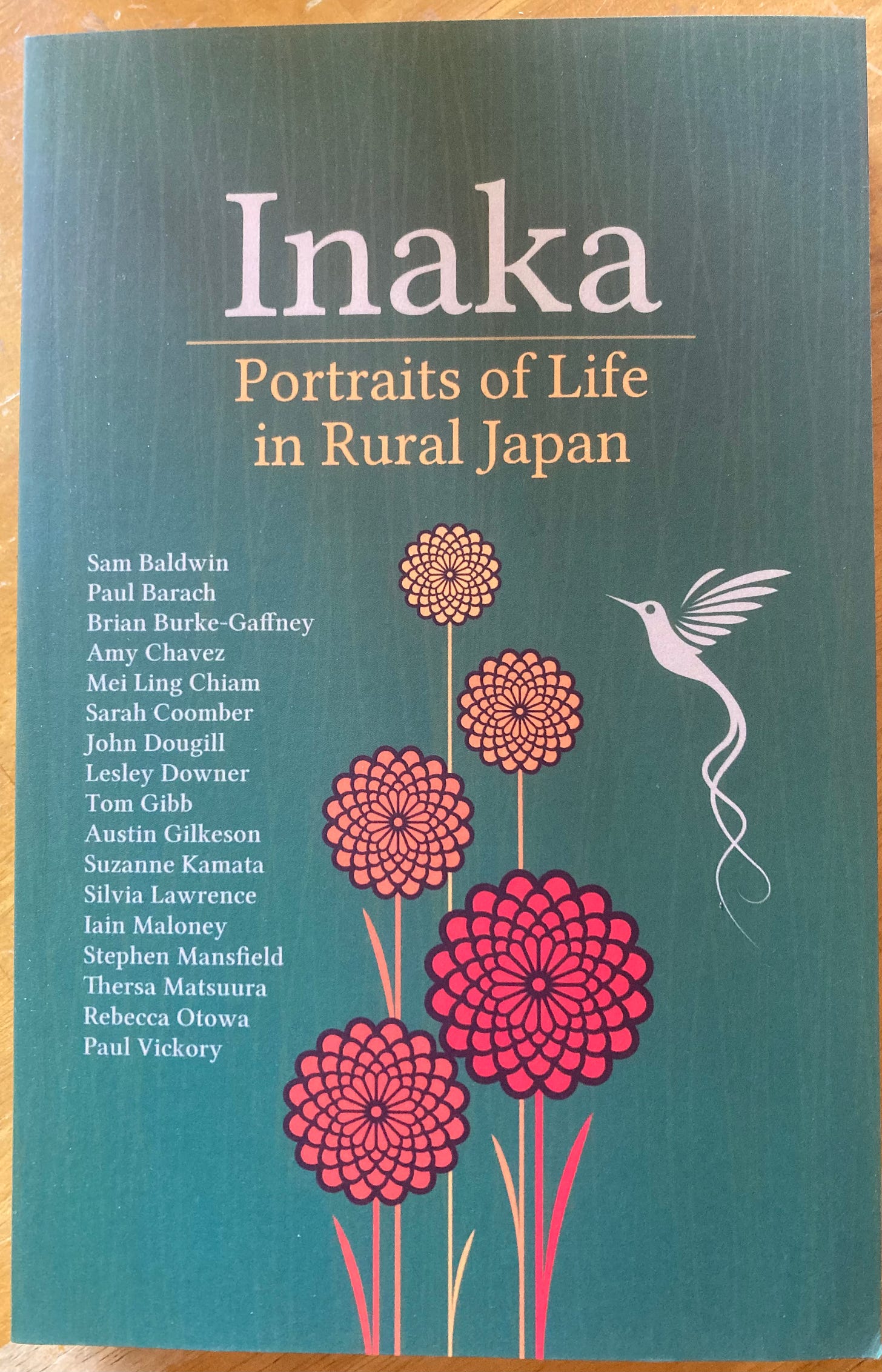

Originally published in Inaka: Portraits of Life in Rural Japan (Camphor Press, 2020).

My village is equipped with a PA system for public service announcements. A combination of volume, treble, and the surrounding hills reflecting the sound in seemingly chaotic directions means that they are rarely understandable, at least to me. I can occasionally make out verbs in the mush but usually have to rely on my wife for a translation. I will consider myself fluent in Japanese the day I understand one of these announcements without help. The most common broadcast concerns elderly people who have wandered off.

Counterintuitively, these disappearances seem to increase in the winter. I’d have thought that regardless of the grade of senility, the depth of the Alzheimer’s, or the degree of confusion, the bitter winter temperatures would have tweaked some subconscious survival instinct and kept them indoors. Apparently not. Or perhaps the number of wanderers is constant, but in winter the waiting time before calling in a missing person is much reduced. Whatever the reason, the end of 2019 and the start of 2020 saw a plethora of PA blasts.

One day in particular stands out. The low temperatures, the lack of decent insulation in Japanese houses, and the environmental impact of electric or kerosene heaters means on the weekends we tend to stay in the warmth of our bed far later than is decent in non-students. Minori, after years of refusal, has belatedly got into Game of Thrones, so every waking moment is another episode. I’m reading Patti Smith’s Just Kids, and a standoff is underway over who will make the coffee. Around nine the tinny BING-BONG of the PA reverberates around the village. I make out the verb “missing.”

“Who is it?”

“An eighty-four-year-old woman is missing.”

I go over to the window and peer out.

“She isn’t in the garden.”

“We’ve done our bit. Since you’re up, get the coffee.”

“Dammit.”

I’m no sooner back upstairs with the tray when the PA bing-bongs.

“They’ve found her.”

“That didn’t take long.”

“She was probably just in the garden and no one wanted to go out in the cold and check.”

We settle back in to our respective distractions. Reading about young romantic poets and artists in 1970s New York doesn’t really work with a soundtrack of dragons, violence, and sex, so I soon give up and watch along with her.

“Where’s Arya at the moment?”

“Shhh.”

“I just want to know where you’re up to.”

“No spoilers.”

“But I can pinpoint exactly where you are in the story by where Arya is in her travels.”

“Shhh.”

“Who’s died recently?”

“You if you don’t shut up.”

BING-BONG.

“Another one?”

“Yes, a seventy-six-year-old man.”

“Sato-san is seventy-six.”

“If he’s wandered off, it’s because he wants to. He isn’t senile.”

“He was asking me about some English phrases the other day. Apparently he unearthed some of his university textbooks.”

“Maybe he’s off traveling. What phrases?”

“Mainly ‘I have a mind to....’”

“Did he want lessons?”

“No, I —”

BING-BONG.

“Again?”

“Yep, they found him.”

“What’s going on this morning?”

“Probably as soon as they hear the announcement they go ‘Wait, that’s me. I’m not missing, I’m right here.’”

“They need to be more careful. You know the story of the boy who cried wolf?”

BING-BONG.

Again? I figure we don’t have to listen this time.

“There was a story doing the rounds a while ago. In this town in America, a woman went missing, so the whole town turned out to look for her. They were out for hours, all through the town, the hills, and forests, tramping through the brush, looking for her. It was only when they gave up and regrouped that they realized the woman they were looking for was part of the search party.”

“Would you shut up?”

“Seriously?”

This time is different. The announcement goes on. And on. They usually repeat twice, but this one just keeps on keeping on.

“What the —”

“Shhh.”

“Is someone missing?”

“Shhh.”

“Is it about a wolf?”

“Shhh. No, a dog,” she says.

“What?”

She starts laughing. The message finally ends and loops back to the start.

“It was the police. One of their dogs has run away.”

“Are you joking?” I say.

“Nope. It’s run off, and they’re telling everyone not to approach it. Aren’t those things really well trained? Why would it be dangerous?”

“They’re trained to obey only their handlers. They wouldn’t be much use if a criminal could just yell ‘sit!’ and the dog obeyed.”

“It can’t be that well trained if it ran off,” she says.

“Maybe the training is brutal and the dog saw a chance to leg it.”

“Maybe it wants to travel. It’s a working dog, so it might need a holiday.”

“Not much of a holiday in Gifu in mid-winter.”

“It’ll go north into the wild. Live like a dire wolf,” she says.

“You’ve been watching too much Games of Thrones.”

“I want a dire wolf.”

“They’d be good if we had burglars. Maybe it’s looking for sex. Off on the hunt.”

“You’ve been watching too much Game of Thrones.”

The area around the village is perfect for hiding, especially if you’re a clever dog. Minori’s right: it would head north. To the north it’s all hills and forests. There’s cover to the horizon where the Southern Alps start. I wish it all the best, on the run from the cops. Its training can now combine with its instinct. I picture it as an Alsatian, bounding through the snow, ducking branches. Run! Be free! I hope you find what you’re looking for.

In Furukawa Hideo’s novel Belka, Why Don’t You Bark? the descendants of Kita, a Japanese military dog, spread around the world, mixing their blood with the descendants of Belka and Strelka, Soviet space dogs. Some become military dogs, some do more clandestine work, some are sled dogs, others win competitions. Two of them, Ice and then Sumer, roam the wilderness of North America in search of safety, in search of freedom, in search of a life away from the world of men. Ice dies on the way, hit trying to cross a highway, leaving seven puppies behind. Sumer, a show dog whose puppies have been sold is in the truck that hits Ice, on her way to be destroyed. She escapes, takes Ice’s puppies under her guardianship and leads them south, to Mexico.

There is a history of books that focus on animals, usually pets: Soseki Natsume’s I Am a Cat, Virginia Woolf’s Flush, George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Richard Adams’s Watership Down, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, to name a few of the more famous. They tend to fall into two camps: books for children or satires on the human world using the non-human perspective to defamiliarize whatever it is the author has a beef with. Belka, Why Don’t You Bark? is neither. It is only tangentially connected with humanity, and then only the criminal fringes. It is, in many ways, a new form of literature that opens the animal world up to fiction in a way that sidesteps basic anthropomorphism. Science fiction without the need for inventing aliens. The dogs aren’t humanized animals; they are dogs with their own voices, own perspectives. It’s a special book, entertaining and groundbreaking in a subtle way. It’s also given me a framework in which to fantasize about the police dog’s emancipation.

As I lie in bed waiting for the inevitable pattern to reform itself, for the BING-BONG saying the police dog has been found, I imagine her — I’ve decided she’s female — stretching her muscles, running like she’s never been allowed to run before. Summer — I’ve named her Summer, after Furukawa’s Sumer, and because while winter is here, summer is coming — has the forest in her nostrils, the mountains in her eyeline, the wind to her back, and the snow under her paws. She’s free in a way only the incarcerated can experience, and in that moment I envy her that thrill, that vital experience. Run, Summer, run. I grew up in the woods. There’s a hum, a vibration of life and energy between the trees. We came from there, from up in the branches. Our DNA remembers.

Summer’s escape touched me because it cast light on the disappearance of my own pet. Ten years ago, we bought two turtles, each no bigger than a ten-yen coin. One died years ago; but the other, Lincoln, lived on. Specifically, he lived on in a huge plastic tub with a series of rock islands and bridges. I’ve been meaning to dig a pond in the garden since we moved in; but being thoroughly untechnical, I can’t quite get my head around the series of pumps I need to stop it from turning into a primordial soup that produces endless mosquitoes. So Lincoln remained in his plastic home. Last summer, during the rainy season, I bought a few huge ceramic pots for the garden. Once they’d filled with rainwater I added a few plants and some goldfish. In the tall, deep ones, the fish seemed happy; but the shallower one for some reason wasn’t ideal, and the fish soon died. I thought Lincoln might like a change, so I experimented with different sizes of rock and soon built an Atlantis that gave him places to hide, places to bask in the sun, places to eat and defecate. Everything except a means of escape.

See, Lincoln had long showed signs of edging towards emancipation. Eating and swimming were clearly not enough for him, and as someone who suffered through numerous family holidays poolside with three natural born sunbathers I could see his point. I sympathized, but not enough to cast him out into the wilderness. I suggested buying him a mate, like a cowboy celebrating his son’s first birthday as a man, but Minori put me off such pimping and procuring, pointing out the problems of breeding turtles. So Lincoln’s urges remained unfulfilled. Like so many other reptiles, he was an involuntary celibate, an incel, but luckily had no access to the internet to share his failure.

Instead, like Summer, and like my elderly neighbors, he did a runner.

I’d made sure that none of the rocks he basked on were anywhere near the edge, and the sides of the ceramic bowl aren’t just vertical, they curve back inside so only the most attention-seeking of Californian climbers would attempt to scale them. Unfortunately, I hadn’t taken climate change into account.

This part of Japan is relatively mild. Typhoons rarely make it this far inland; but in the last couple of years, as climate change plays havoc with the usually predictable weather, encroachment of the more extreme forms of precipitation has increased. We battened the hatches, cleared the garden of anything that could take flight, and slept through the worst of it. Come morning all was sunny and serene. The aftermath of a typhoon — assuming no damage — is a moment I enjoy. The air crackles with spent energy, like things are falling back into place, like the whole world is breathing a sigh of relief, stretching out, and throwing the windows open. I took a stroll around the garden, tidying up anything that had shifted, sweeping leaves from the road, breathing in the crisp air.

It was Minori who noticed first.

“Lincoln has gone.”

“You sure he’s not under his rock?”

“Check.”

Sure enough, his hideaway was empty. I pulled all the rocks out just to make sure.

“Yep, he’s gone.”

It hadn’t occurred to me that the rain would raise the water level to the brim, spilling over, enabling Lincoln to tip himself over the edge. We hunted around the area, overturning anything he could hide under, but there was no sign. He’s no bigger than a saucer, with tiny little legs, so he couldn’t have gone far. There are no rivers or streams near the house, nothing like a natural habitat for him; but as wide a search area as we tried, he had gone to ground. Perhaps literally.

“My dad says they dig into the sand in winter.”

“It isn’t winter.”

“Yes, but I mean they can dig. Maybe he’s done that.”

“He can’t stay there long. They have no gullet, so he can’t eat unless he’s in water. He’s going to starve.”

As we searched, a few of the neighbors, Sato included, came out to see what was going on. A small search party assembled but uncovered little beyond mushrooms and stray litter. I made a joke about using the PA system to announce Lincoln’s disappearance, but my neighbors don’t usually get when I’m joking and told me that the system couldn’t be abused like that. Sato laughed. He gets my jokes.

Sato is seventy-six and very proud of the fact. He is happy to have achieved this age and retained his health and marbles. In every conversation he quickly turns the topic to his age, crowbars it in whatever the subject. It’s strange then, given how much he acknowledges his age, that he seems to consider himself in the full flush of youth. His neighbor Koizumi-san is seventy-seven, but Sato refers to him as “that old duffer next door.” Clearly that year matters a lot to Sato, and he defines himself in part by his relative youth. To be fair there is a big difference between them. Koizumi shuffles along, rarely has much to say for himself, and never strays far from home. Yamada on the other hand takes long walks every day, keeps up his piano playing, and, it seems, has picked up his English textbooks after decades of neglect.

English education in Japan is a complicated topic and one I won’t get into here, other than to say this. At school the conversational side of English is ignored in favor of translation, memorizing vocabulary and grammar forms, and listening to recorded exchanges. It’s understandable from a teaching perspective in a country where class sizes are regularly in the forties, but it has two drawbacks: one evident, one less so. Obviously this means that students who get the best marks in English at school may be unable to hold even the most basic conversation. It also means that as students progress from elementary school through junior high school and high school, the vocabulary and grammar forms they are forced to learn become increasingly obscure. There simply isn’t enough language to fill hours every week for nine or ten years. Hence Sato having a textbook with a lesson that focuses on the structure “I have a mind to....” Sato can’t speak English. I had no idea he’d even studied it; although it’s compulsory now, it wasn’t always. When we talk it’s entirely in Japanese, not even the code-switching hybrid most of my conversations are these days. If Sato is keen to converse in English, “I have a mind to” is probably not the most useful place to start.

“When would you use this?”

“I wouldn’t really. But it’s used when you are thinking of doing something that you probably shouldn’t, or something that may be surprising to the person you are talking to. For example, ‘I have a mind to tell my boss exactly what I think of him.’ Or ‘I have a mind to quit my job and go traveling.’”

He thinks for a minute.

“So I could say, ‘I have a mind to tell Koizumi to cut his bushes’?”

I laugh, “Yes, something like that.”

The day of Summer’s escape I finally haul myself out of bed. As always, it’s much warmer outside than in. I go down to the end of the garden where I’ve been pruning trees. This is where I’d build my pond, Lincoln’s pond. Far enough from the trees that the roots wouldn’t interfere with the lining or be damaged by my digging but close enough for the cherry blossom to hang poetically over the water. It would back against the wall, follow its straight line, before curving out unevenly like a misshapen B. I like the misshapen. Geometry has no place in nature. I might put mesh across the middle, so I could have fish and turtles, without the former being lunch to the latter. I have a cairn of rocks kept to line the perimeter and to form islands in the stream. I have it all worked out, apart from the mechanics. The other thing that’s stopping me is the neighbors.

“Cold today, isn’t it?”

Sato is returning.

“You must have warmed up on your walk?”

“Yes. It does me a world of good. Keeps me young. What are you up to? Tidying the garden?”

“I have a mind to build a pond,” I say in English. He laughs, recognizing the form but then shakes his head.

“Koizumi has a pond.”

“Does he? I haven’t seen it.”

“Round the back. It stinks. He never cleans it. And in the summer the mosquitoes are everywhere. Every year I tell him, and every year nothing.”

“Yeah, I was worried about the mosquitoes. I thought with a pump and a filter, with the right plants it would be okay.”

“Maybe,” he says, not looking convinced. By association with Koizumi, the very concept of a pond has been tainted. “Did you hear about the police dog?”

“Yes. Were you okay out walking? They said it might be dangerous.”

“I didn’t see anything. It’s probably long gone.”

“Where would you go if you were a dog? I thought it would head for the hills.”

“Straight to Kawai-san’s.”

“Kawai-san?”

“The butcher in N— Village.”

“Ah. Yes, that would make sense.”

“He has very good meat. You should try him next time you have a barbecue.”

“I will, thanks.”

I hadn’t realized that dire wolves were real things. They lived in North and South America during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene epochs (150,000–9,500 years ago, thanks Wikipedia), the canine companion of the saber-toothed tiger. Unlike their fictional cousins in Game of Thrones, they weren’t giants, perhaps a touch bigger than modern wolves. Japan, like Scotland, used to have wolves but hunted them to extinction. There were two types of wolf in Japan, the Honshū and the Hokkaido. The latter was also known as the Ezo wolf, Ezo meaning foreign or outsider – the old name for Hokkaido, home to the Ainu people before full colonization in the nineteenth century. When Hokkaido was brought into Japan proper, the wolf was exterminated with a bounty system and mass poisoning.

The Ainu too are all but extinct, their culture and language hanging on in Hokkaido mainly as a tourist attraction. I visited an Ainu village in 2018. At the time I had a huge beard that had gone untended for close to a year, a big bushy mess. One old man in the village told me I looked like an Ainu elder. I was inordinately pleased. I bought a two-meter square wall hanging from him that keeps demons from the door. For the Ainu, the wolf was a holy creature, divine, to be worshipped. To kill one with poison or firearms was taboo. They were considered to be beneficial animals across all of Japan — they kept wild boar numbers down, helping farmers. They were thought to protect travelers. There are shrines to them around the country. Now they are all gone.

In Scotland, wolves are part of the rewilding discussion. The UK is the only place in Europe that doesn’t have wolves. They are good for the environment, helping bring ecosystems into balance, keeping an equilibrium among animals. They are also good for our spirits. The wild should be wild. Untamed, out from under the heel of man. Wild doesn’t mean chaotic, not when we’re talking about ecosystems. Wild is balanced. Order is unnatural. When we try to order nature, things die, go extinct. Hokkaido was brought into line. The wolf had to go. That’s the price of order. Extinction. But we are part of nature too; our spirits were born in the wild, evolved in the wild. There is wolf in us.

Alex Martin wrote in the Japan Times in 2019 about a potential wolf sighting in Saitama, north of Tokyo. Rumors that packs survive have been around since the last known wolf was killed in 1905. There’s romance in the article, an underlying dream that somewhere among all the controlled sterility of modern life something as raw as the wolf is holding on. An underlying wish that the animal that represents the feral nature of our origins — see the founding of Rome by the wolf-suckled Romulus — still exists in places it’s thought to have been eradicated from gives us secret hope that our true nature, the wandering, nomadic, adventuring humanity, survives in the antiseptic twenty-first century. That we too, like Summer, can one day, metaphorically at least, run free through the woods, feeling the wind at our back and the snow under our feet.

We have a mind to flee. We have a mind to run. But we don’t, because we have jobs and mortgages and responsibilities, bills and payment plans, and kids that can’t fend for themselves. We aren’t wolves; we aren’t even dogs or turtles, but that instinct is still inside us. While I read about the poverty-stricken freedom of Patti Smith and the artists of the Chelsea Hotel exploring their freedom of the mind, and Minori watches Arya Stark crisscross Westeros exploring what it’s like to be a woman freed from societal conventions around her gender, free to follow her desires and ambitions, we dream in our modern human way about a freedom Summer and Lincoln are experiencing. Perhaps this is the drive that kicks in when senility breaks the narrative: movement, travel, adventure. The elderly around here are off, exploring their natures, until the PA system lassos them home.

Or is it mortality? Many animals take themselves off when death approaches. Was this instinct also once in us, back when we were in the trees? Is it there, a behavioral appendix, after all this time, only surfacing when age withers consciousness and its defenses? A slow countdown that powers our legs.

Maybe all of this is age, even though Sato still considers me a kid, a young ’un, a whippersnapper. I’ll be forty in a few months and I’m keeping a weathered eye out for any clouds that resemble a midlife crisis. Is envying a dog and a turtle their freedom a sign? I ended up in rural Japan by following that adventurous nomadic spirit, leaving Scotland behind to see what the world had to offer, tipping myself out of a familiar, safe environment and diving headfirst into the storm. I catch myself looking at job adverts. Minori and I discuss a vacancy in Abu Dhabi. I recall one in Kazakhstan a few years ago and wonder what would have happened had I applied. I’ve settled down, house, mortgage, the works; but that wolf in me isn’t asleep. He yearns to run for the hills. I can see the same thing in Sato, a restlessness, a sparkle. He envies his daughter her experiences in China, envies me mine in Japan. His return to studying English may be a symptom of that — dreaming of travel through the pages of a textbook. But he’s also happy where he is. A few days before New Year I find him sweeping up leaves outside his house, trimming the bushes, applying a very human order to things.

“My daughter is on her way,” he says, “with the grandkids. This place is a mess, I want everything to be perfect when she gets here.”

“How long will they stay?”

“Two nights. They have to visit his parents too.” His disappointment is palpable. Every journey involves leaving someone behind. This is a pain we didn’t evolve to deal with. We would have been nomadic together, extended families traversing the steppes in each other’s company, and later being born and dying in the same village. The idea of heartstrings, of the tugging. Every journey means a stretching of bonds, a breaking of ties. In Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, taking a child away from their daemon causes both physical and emotion wrenching. Distance equals pain.

Does Summer look back as she runs? Does Lincoln think about that big shape that fed him and washed his home, giving him fresh water when he’d shit the whole place green? Is this what defines us as modern humans, the tension between the wolf’s urge to run and the bird’s urge to nest?

“Are you going home for New Year?” Sato asks me.

“No, I don’t these days. Traveling at this time of year is too much trouble, and so expensive.”

“Your mother must miss you.”

Arya Stark is free to roam only because she thinks everyone is dead. The heartstrings permanently severed.

Inside, Minori has the heater on. I have a bottle of Japanese whisky made in the traditional Scottish way. Arya is going back to Winterfell, her brothers and sister already there. Lincoln never came home. Neither did Summer. At least, there was no follow-up announcement, no BING-BONG closing the circle. If they tracked her down, they kept it to themselves. I hope she made it to the mountains. I hope Lincoln made it to a river. I keep expecting to overturn an empty shell while I’m digging the vegetables or the compost heap. So far, nothing. I hope whatever thought or instinct that drove Lincoln to take advantage of the storm, to pull a Tim Robbins in The Shawshank Redemption, to risk his life for the dream of freedom, that it was fulfilled.

I have a mind to travel. I have a mind to see more of this world. But it’s weaker now than it used to be. I no longer have a mind to dive over the edge and head out into the storm without a thought for what I’m leaving behind, without an idea of where I’m going. From the window I watch the birds collect on the edge of Lincoln’s former home. They take a drink, tip their heads back, and let the water run down their throats. They shake their heads, look around, take another drink. These birds are from Mongolia and northern China. Jōbitaki, Daurian redstarts. Every year they leave. Every year they come back. The fly over the Sea of Japan, over the Koreas, over China, into Mongolia, where they build nests, lay eggs, and raise their young. Then, when the temperature drops and the north winds come, they climb into the skies, their internal sat-nav set for my garden, for Lincoln’s ceramic bowl where they can refresh themselves and sit out the worst of the winter.

As I age, I’m less like a wolf and more like a jōbitaki. Horizons shrink. Sato could visit his daughter in China but doesn’t. Instead he follows his circuit past the temple every morning, complains about Koizumi, travels through his English textbook, and talks to me about the world beyond the village. It’s enough. At New Year and during the Obon holiday in August, she comes back and he prepares. It is enough. Maybe one day, many years from now, the PA announcement will be for Sato and we’ll find him up behind the temple instinctively following his old path, muttering “I have a mind to travel.” Maybe. None of us know what is out there in the storm, what’s in the mountains on the horizon. But for those about to wander off, I salute you.

Excellent! I can really relate to the village sound system and its garbled messages. Oh, and Game of Thrones! My wife and I binged on that TV program during summer vacation last year and every weekend since until we had finished the entire series. LOL. I really liked how you signed off with the AC/DC nod, "For those about to ...". Awesome. An enjoyable read and an inspiration as always. Regards, Chris