August Reads (part two)

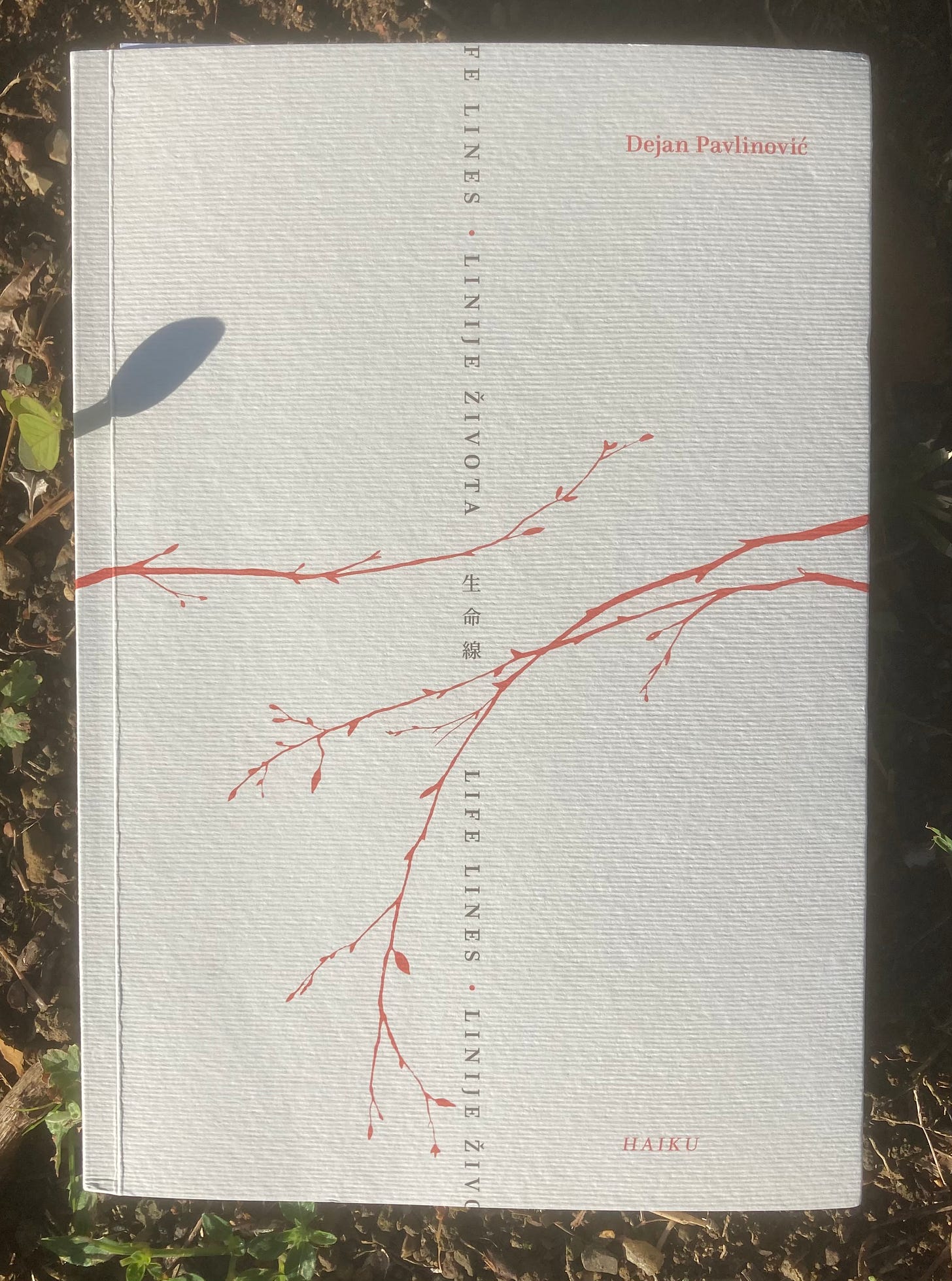

Dejan Pavilnović is a Croatian haiku poet who reached out to me with his latest collection Life Lines. It’s a fascinating trilingual collection of haiku written in Croatian, English, and Japanese. As I understand it, Pavilnović is responsible for the Croatian and English versions, and they were then translated into Japanese by Ikuyo Yoshimura. I actually met Yoshimura once; she lives in Gifu and translated some of my haiku. I had a very enjoyable pizza lunch with her, Alan Spence, and his wife. Good times. I can’t comment on the Croatian versions, but the English and Japanese poems are excellent, powerful, witty, thought-provoking: everything good haiku should be. I particularly liked “full moon… / walking the shutters / on her naked back” and “trapped / in honey jars / autumn colours”. I’d heartily recommend this book to fans of haiku outside it’s original Japanese context. For anyone learning English, Croatian, or Japanese, this would be a cool way to study too.

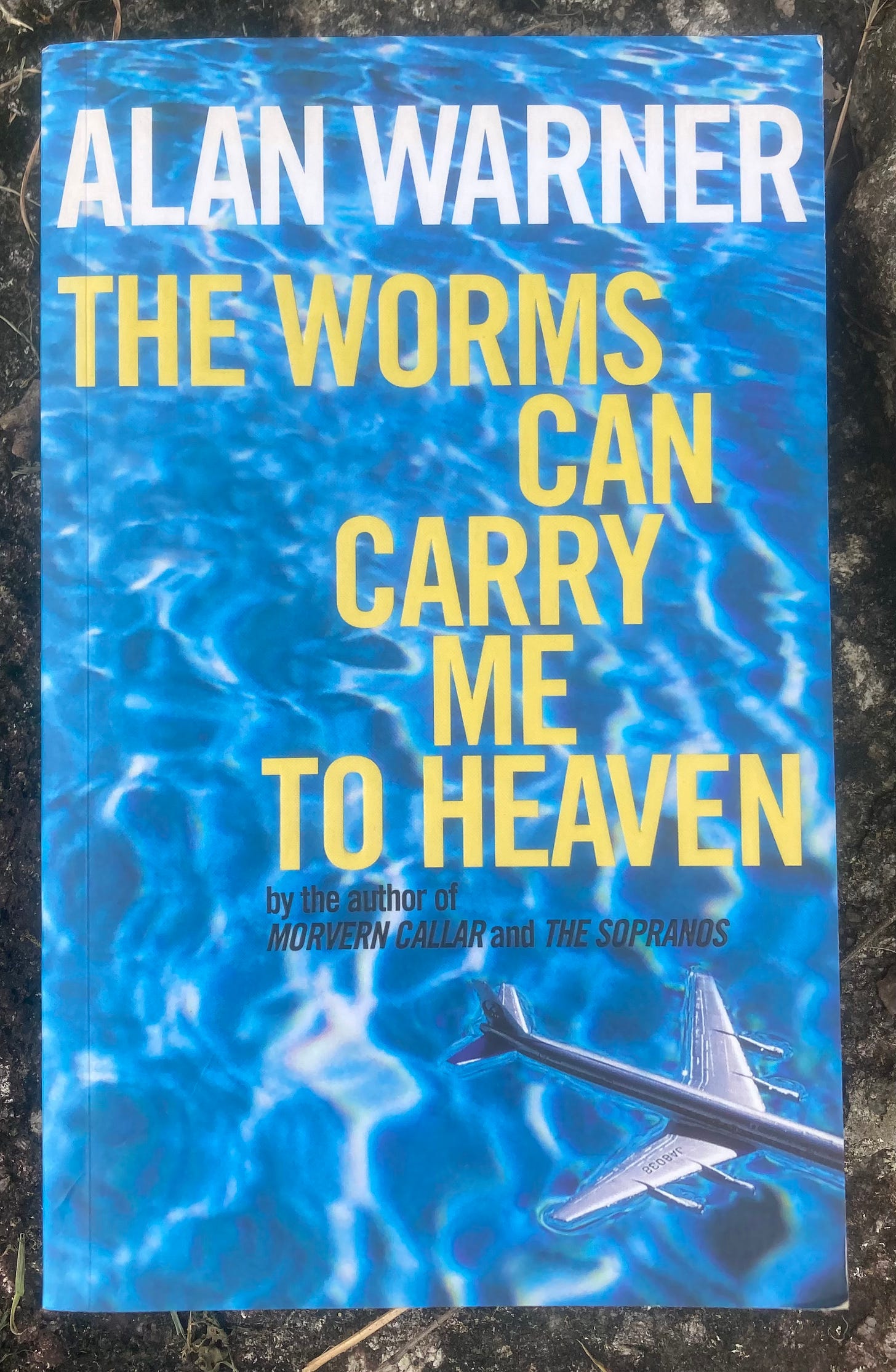

I adore Alan Warner and Nothing Left to Fear from Hell is still one of the best books by anyone I’ve read recently, but this was a little disappointing. It shows his versatility and range, and is hilarious in many, many places, but I found my attention wandering quite often and sometimes couldn’t read more than a chapter before I put it down. Doesn’t change my opinion of Warner, but I can’t see myself revisiting it.

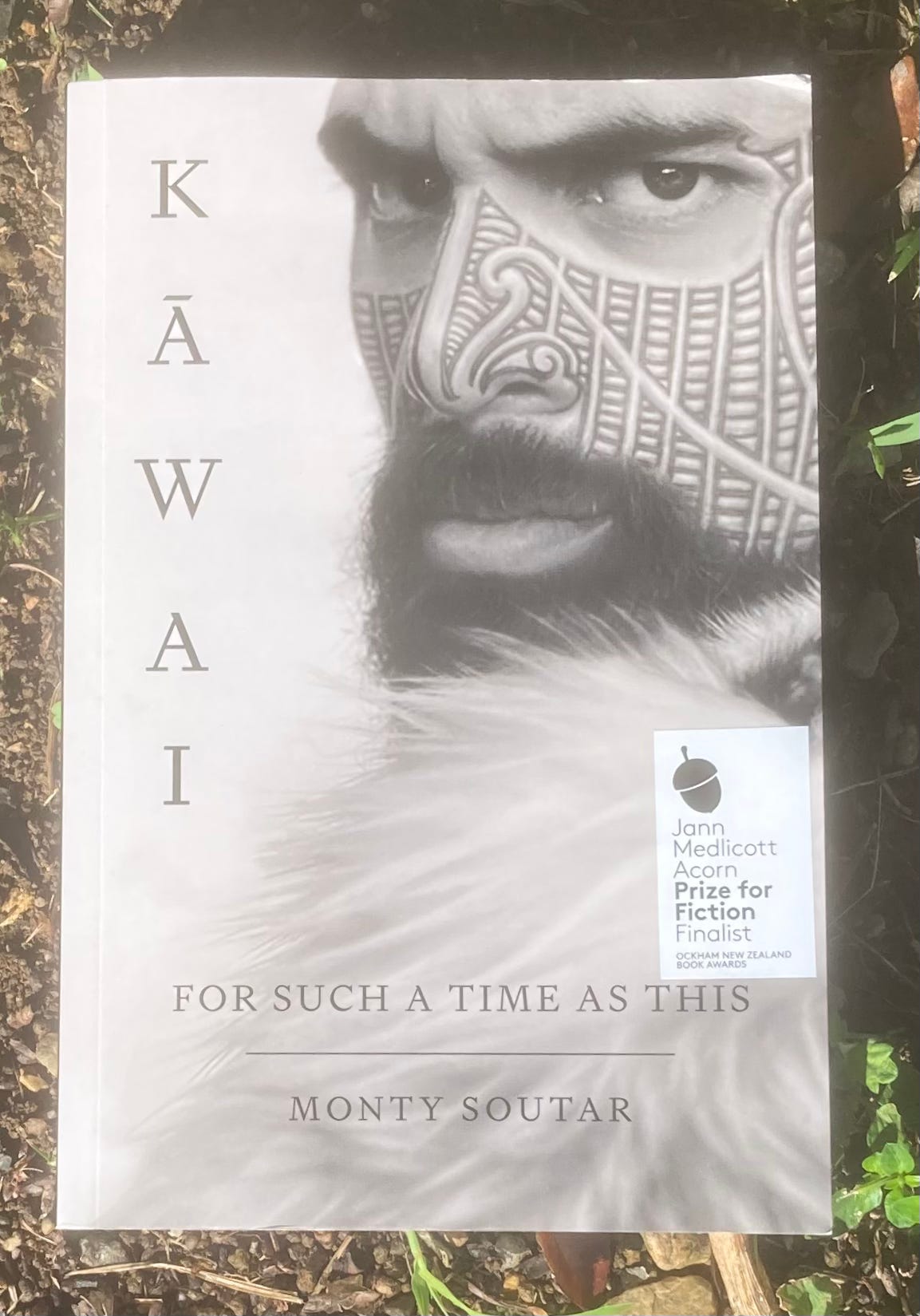

I picked up Monty Soutar’s Kāwai: For Such a Time as This in New Zealand last year but, as is too often the case, it sat on the shelf longer than planned. Framed by a narrative in the 1980s, the bulk of the book is set amongst the Maori community in the mid-18th century, and tells the life story of a legendary warrior, Kaitanga. The story is generally compelling, and really exciting during the battle scenes (of which there are more than a few), but the pace is uneven. There are quite a few chapters, particularly at the start, which seem to exist in order to show a specific side of the author’s research into Maori culture rather than advance the plot. These are small complaints however, and the overall book is an interesting historical adventure.

24 year old Charles Robert Jenkins was serving in South Korea in 1965. Scared of being reassigned to the war in Vietnam, he got drunk, went AWOL, and crossed into North Korea. Today it seems utterly bizarre that someone might think to seek refuge in North Korea but at the time Jenkins apparently assumed he would quickly be arrested, returned, court martialed and kicked out of the army. Instead he remained in North Korea for 40 years, eventually being returned to Japan along with some Japanese abductees, one of whom had become his wife. If you’ve read any accounts of life in North Korea, little of it will surprise you. It’s interesting to see it from the perspective of a US soldier, the literal enemy of the regime, and Jenkins seems never to have suffered Stockholm Syndrome and is never anything but scathing of the regime. He’s not the best writer in the world (Jim Frederick is a journalist but the majority of the books just seems to be transcribed almost verbatim) and as you can tell from above wasn’t the most knowledgable about geopolitics or North Korea before he cut himself of from the media for four decades, so the depth of analysis isn’t great. Still, it’s one of those “you couldn’t make it up” stories.

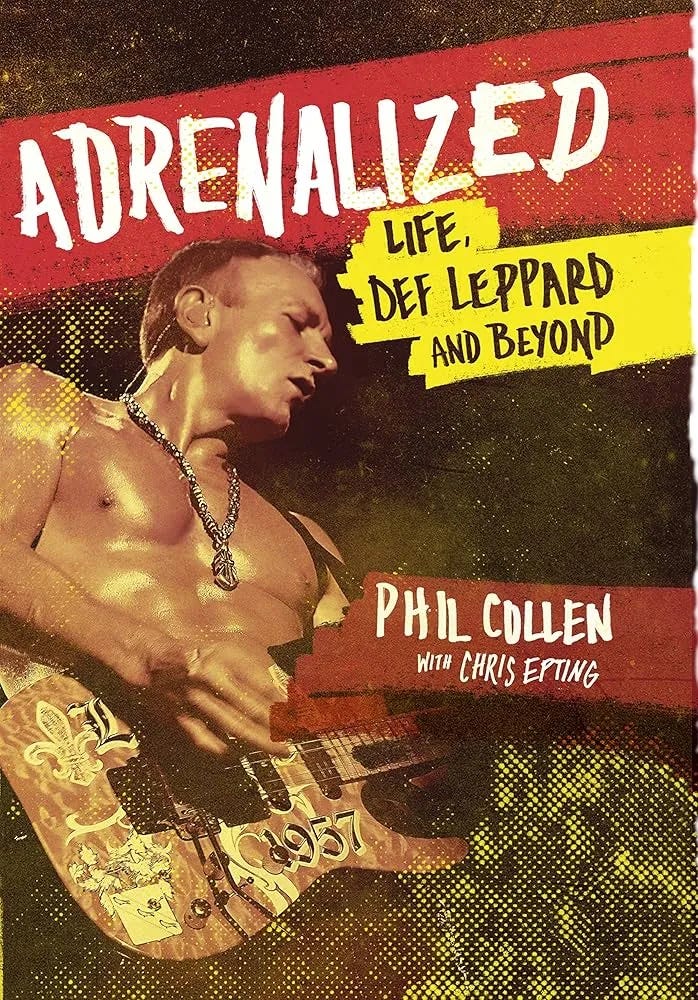

More of a completist thing than anything I was particularly desperate to read (I’m hoping to be involved in a music book project in the near future), there is little in this that would be new to a Def Leppard fan and little of interest if you aren’t. As always with rock star biographies (although I’m going to contradict myself with the next book) the early days are the most interesting. Sneaking into gigs, getting drunk and high, living the teenage musician’s dream is all great fun. He’s pretty candid about the whole thing and while there’s some understanding that times have changed, he’s pretty unapologetic about some of the things he and the band got up to. The latter parts are mostly about his ever changing roster of wives and girlfriends, the band’s attempts to stay relevant, and his veganism and body building; they were somewhat repetitive. Niche reading, I’d have to say.

I was never a huge Napalm Death fan—never had anything against them but never did a deep dive—and got a signed copy of this as a present from my friend Francis who tangentially knows Shane Embury (bass player of Napalm Death). Because I didn’t know much about the band beyond the headlines and a few tracks, this was much more interested to me than Phil Collen’s book. Again, the early days are fun, but Embury’s career seems to have got more interesting as he has gone on, bucking the trend I mention above. More bands, changing genres, experiences outside music good and bad: this made for a very enjoyable read. Again, if you’re not at least partially into this kind of music, there’s not much point, but as music autobiographies go, this is a good one. Honest about the mistakes, not glossing over things (as far as I can tell), and not seeking to self-aggrandise, I’m now going to do that long-over due Napalm Death deep dive.

I know it’s odd to throw in a guidebook but firstly, it’s probably the book I spent longest pouring over this month, for obvious reasons, but secondly, I want to extol the virtues of the physical guidebook. The internet is full of advice for tourists but most websites tend to just repeat the same five or six things, are so full of adverts you can’t find the damn information you need, or are skewed by crappy or fake (Tripadvisor I’m looking at you) reviews. The Lonely Planet series isn’t perfect but being physical makes it a damn sight easier to use (I know I’m coming across as a Boomer, but flicking from one page to another to cross-reference information is a hell of a lot quicker than scrolling and fighting with ads and cookie announcements) and on those occasions where my battery died or I couldn’t get a signal, it was still reliable. Yay for guidebooks.

Finally, That Was, was something of a disappointment. It’s not bad per se, but it’s not the kind of fiction I like. Lashings of description—places, people, weather, scenery—that contribute nothing to plot or character development beyond the most basic scene setting or overdone pathetic fallacy. By chapter three I realised I couldn’t care less about the narrator or her journey. Or more accurately, I’d learned so little about her and her journey while being drowned in flowery prose that I had nothing to pin my sympathy or interest to. Again, not saying it’s bad, just really not to my taste.